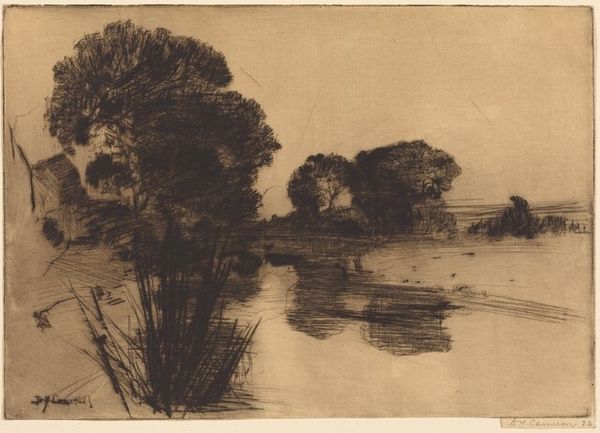

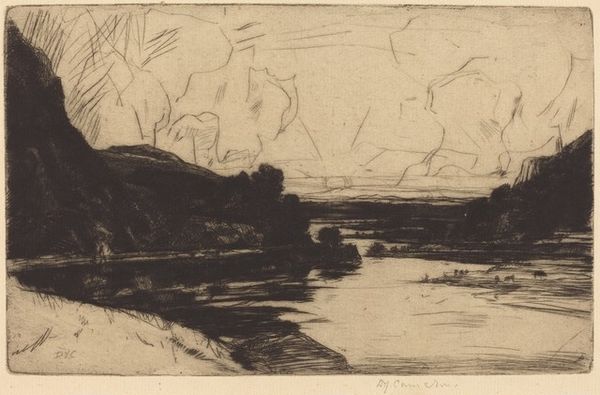

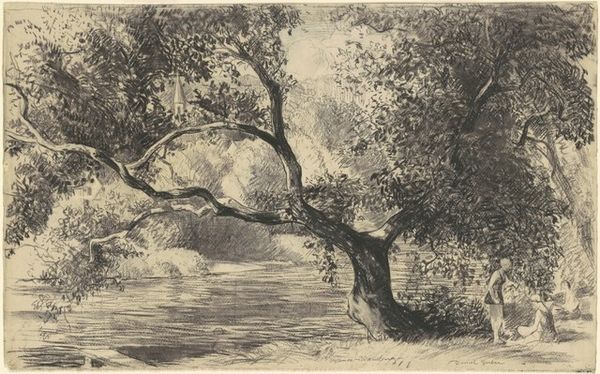

Dimensions: plate: 15.2 x 22 cm (6 x 8 11/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Looking at "A Lowland River: A Dry-Point," created in 1892 by David Young Cameron, it evokes a sense of tranquility, doesn't it? Editor: Absolutely. It has a muted atmosphere, created through the intricate layering of lines, giving it a dream-like quality, but the lines across the front create an almost industrial obstruction in this idyllic place. Curator: It's a fascinating interplay. Cameron, active during the late 19th century, positions himself within the etching and printmaking revival and utilizes the drypoint technique—directly scratching into the plate—allowing for these uniquely burred lines, producing rich, velvety blacks. It's worth remembering, printing at the time was not purely commercial; it was finding itself in fine art, offering more affordable access to images of artistic skill for a growing middle class. Editor: You can really see the hand of the artist here. The network of lines emphasizes the labor-intensive processes inherent in printmaking. Cameron’s skill wasn't just about replicating reality but re-imagining it through these mechanical, crafted means, the materials speaking for themselves. I also keep coming back to those utility-looking lines stretching across the river! Curator: Indeed, it complicates any easy reading of bucolic bliss. The artist would likely be aware of encroaching urbanization that powered the industrial revolution. Editor: This tension between idyllic and intruding form also pushes one to consider not only the artistic value of the scene but also the economic value that may one day displace such views. I feel like the tension speaks to class as well, with print-making becoming more common among the bourgeois as their money literally redraws the very environment that once fostered and cultivated beauty and rurality. Curator: I appreciate that you contextualize the intersection of aesthetics and social change within Cameron's process, suggesting that the mechanical means serve as both replicator and indicator of changing markets. Editor: Absolutely. This wasn't simply the printing of the image of a landscape; it was the production and consumption of culture as industrialization accelerated—affecting the view itself. What do you see as his legacy? Curator: Cameron's precise craftsmanship, seen in the drypoint and etching work, helped solidify printmaking as a significant art form in Britain during this pivotal transition, moving away from its previous status as just an art of reproduction to stand firmly alongside painting and sculpture in museums. Editor: Ultimately, his careful labor leaves behind both a haunting vision of nature's quiet spaces and a silent premonition about inevitable cultural shifts that reshape the material world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.