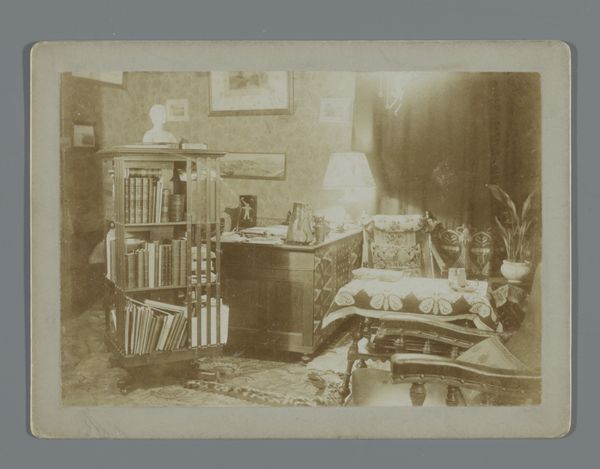

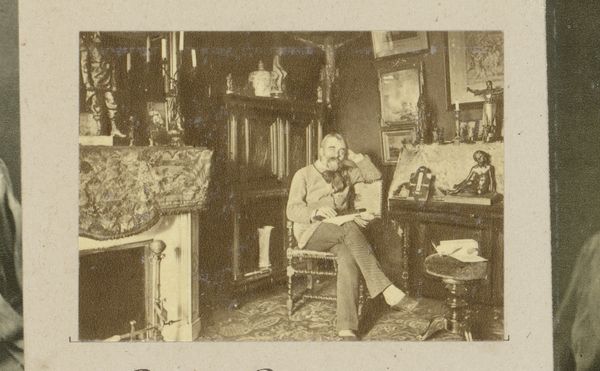

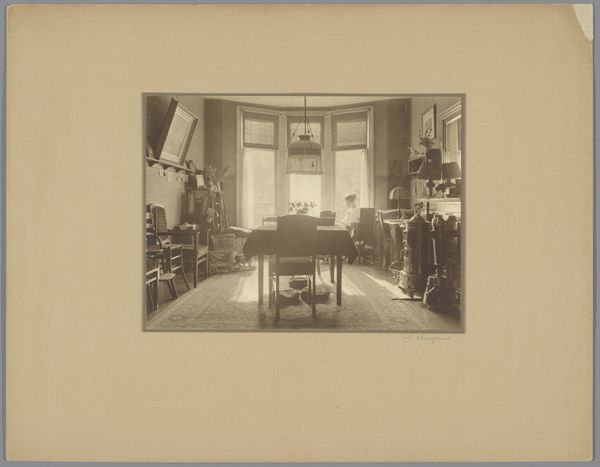

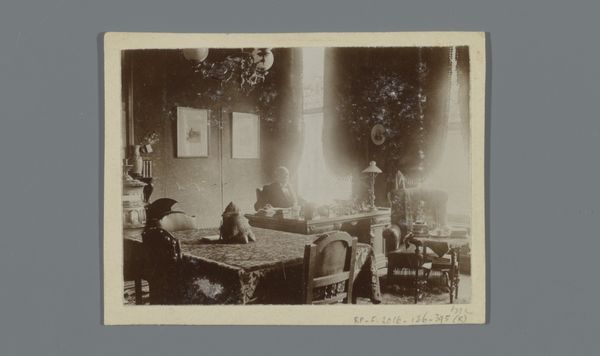

Henk van de Berg achter zijn bureau in zijn kamer op de Turfmarkt 3 in Amsterdam c. 1896

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: height 117 mm, width 169 mm, height 139 mm, width 188 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

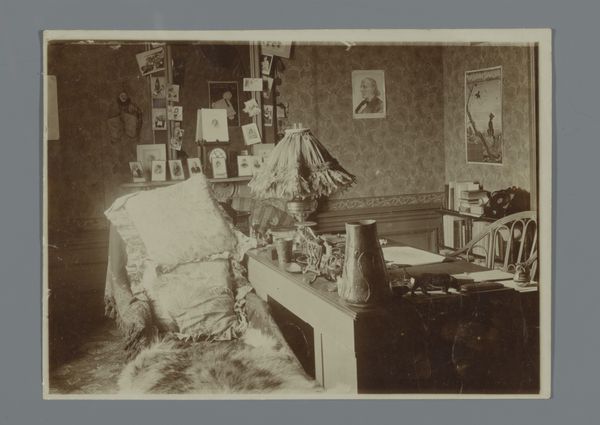

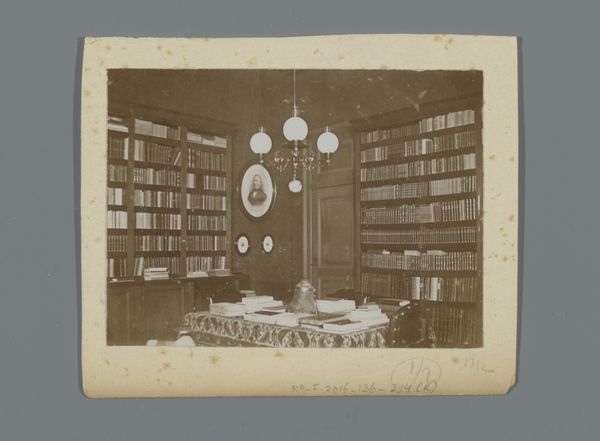

Curator: This sepia-toned photograph, titled "Henk van de Berg behind his desk in his room on the Turfmarkt 3 in Amsterdam", dates to around 1896. Editor: It strikes me as intimate, a peek into a scholar's private domain bathed in soft light, although perhaps a space where class and social hierarchy is quite evident. Curator: Precisely. It gives us access to a professional man’s private chamber. Van de Berg is seated at his desk amidst papers, with shelves of books framing the scene, suggesting intellectual pursuits. I see here not just a portrait, but also a staged "genre painting" about bourgeois life and aspirations. How does that fit in intersectional narratives? Editor: Absolutely. The setting screams privilege and points toward social hierarchies within academic circles. The absence of overt references to his professional position, which as an editor he could make evident, perhaps subtly critiques those very established structures by turning inward towards a reflective practice, and away from an explicitly visible public performance. Curator: The objects – the bust atop the bookshelf, the landscape painting, the ornate lamp – act as signifiers, hinting at refined tastes and cultural capital. This photograph serves as a representation of late 19th-century ideals, the bourgeois academic carefully curating an identity through domestic space and belongings. Editor: Yes, but also the composition creates a certain sense of isolation. He is ensconced there, amidst objects reflecting not necessarily personal taste, but social value. The photograph might unintentionally offer an opportunity to critique not the man himself, but that entire performance. What are your thoughts on the impact of these kinds of images and the culture from which they originated in modern context? Curator: Excellent question. Examining images such as this through contemporary lenses demands acknowledgment of inherent power structures and cultural capital encoded within the frame. How do we make historical moments meaningful without just perpetuating these long established frameworks? Editor: Well, acknowledging the very frameworks that make them meaningful to start and using them for the betterment of future artistic projects. Curator: An ongoing project of critical engagement and understanding.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.