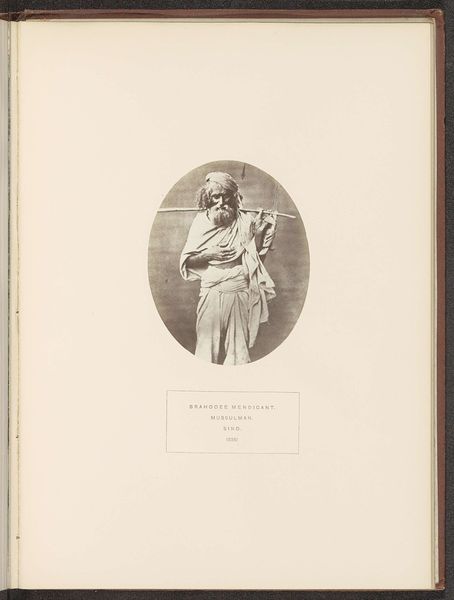

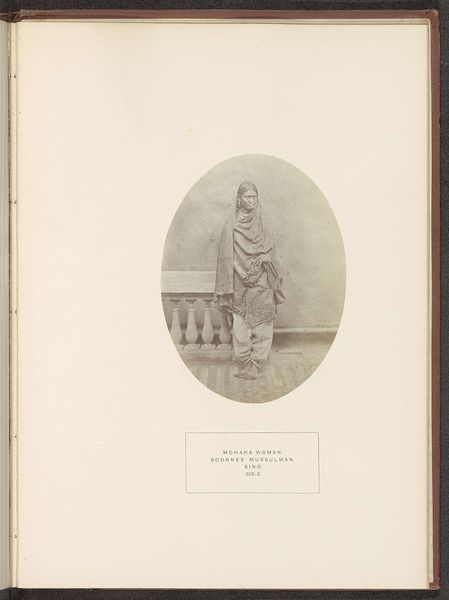

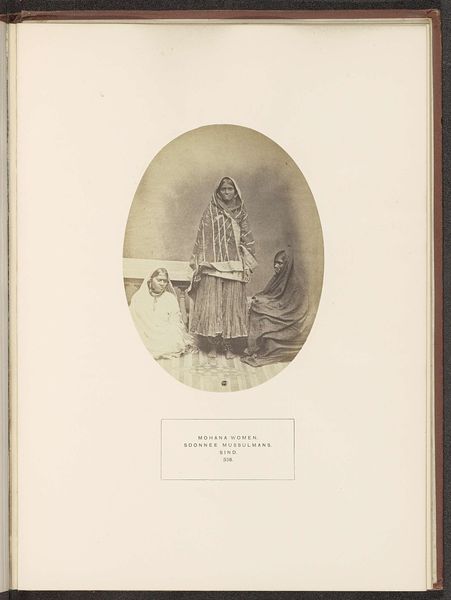

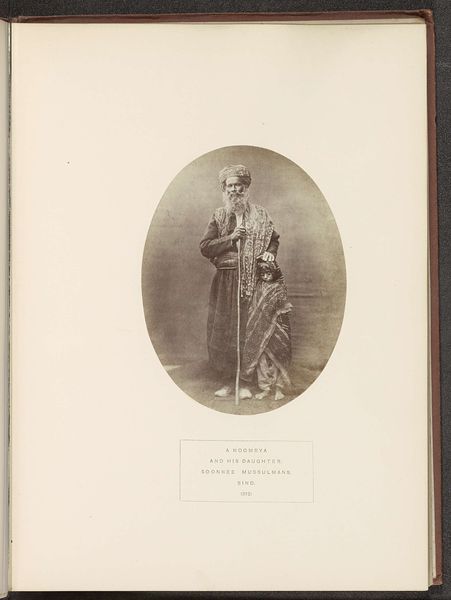

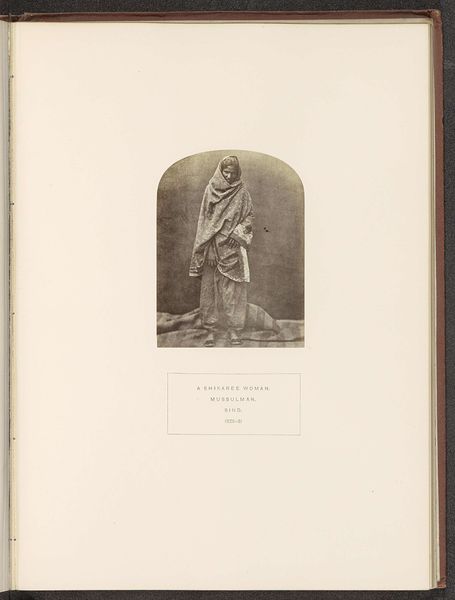

photography

#

portrait

#

photography

#

orientalism

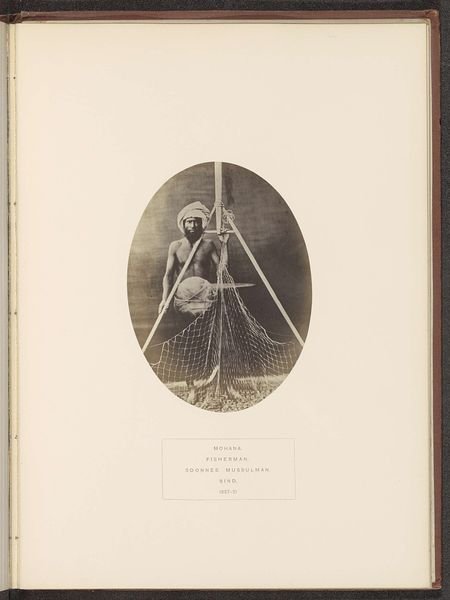

Dimensions: height 129 mm, width 104 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

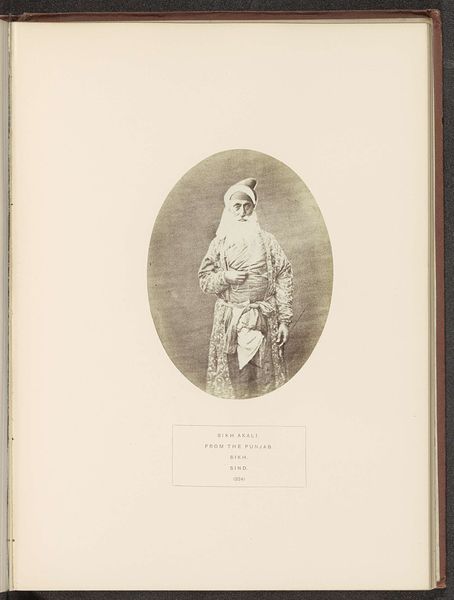

Editor: So here we have a photograph, “Portret van een onbekende geldwisselaar uit Sindh,” or “Portrait of an unknown money changer from Sindh,” created before 1872 by Henry Charles Baskerville Tanner. It has an almost sepia tone, highlighting what seems like a professional portrait. What stands out to you about the image? Curator: I see a complex interplay of labor, materiality, and cultural representation at play here. The sitter's clothing isn't just decoration; it's a product of specific material conditions, skill, and likely signifies a particular social standing and trade, reflecting a colonial-era fascination with "native" types documented through photographic means. Editor: Interesting. The phrase "material conditions" catches my ear; could you tell me more? Curator: Consider the photographer's studio, for instance. Where did Tanner source his photographic supplies? How was the image itself consumed, both locally and back in Europe? What processes were used to develop the print? The "Orientalist" framing reduces him to a type, ignoring any individuality, while simultaneously engaging with, and perpetuating, a hierarchy rooted in material disparity and production. It flattens complex trade networks into a single figure. The backdrop may appear plain, but it’s a manufactured setting designed for the consumption of a Western audience. Editor: It makes me wonder how he might have chosen to represent himself. So much seems predetermined, from our vantage point. Curator: Exactly. And thinking about its circulation, did these images inform policy or contribute to exoticized notions of the "other?" These objects are far more potent as material signifiers when considering such factors. Editor: This really reframes how I see the portrait – less as a simple likeness and more as a node within a larger system of power, production, and consumption. Thank you for sharing that perspective. Curator: Indeed, and I think recognizing this shifts our perception of images that historically were seen just as representations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.