print, photography

#

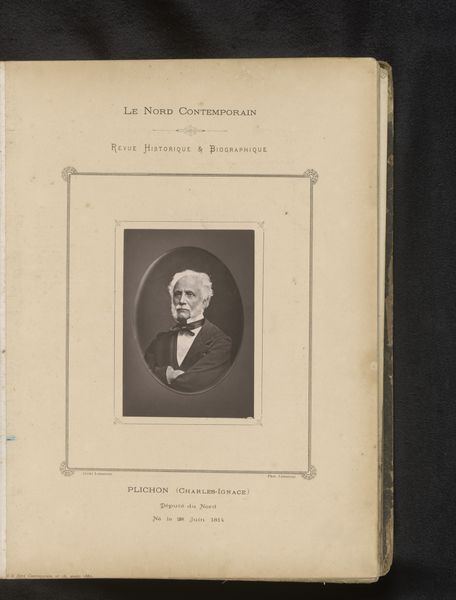

portrait

#

type repetition

#

aged paper

#

homemade paper

#

paperlike

# print

#

light coloured

#

photography

#

printed format

#

fading type

#

thick font

#

white font

#

historical font

Dimensions: height 155 mm, width 118 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

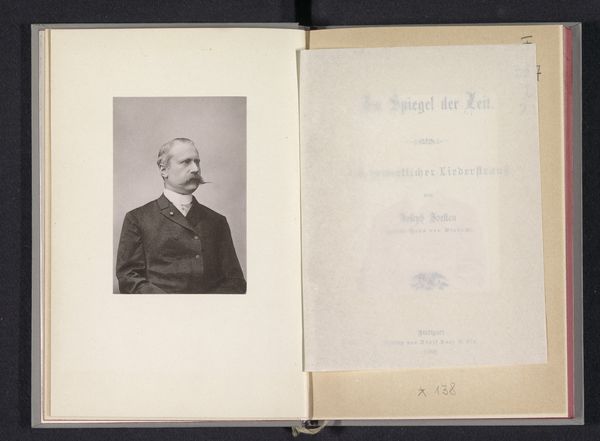

Editor: So, here we have an albumen print from before 1885. It’s an open book, with a portrait of a man, Joachim Heer, on the left page, and text on the right. The tones are quite sepia, giving it a real sense of age. It feels almost like a memento. What can you tell me about it? Curator: This format speaks volumes about the social function of photography in the late 19th century. These kinds of photographic books served as visual records of individuals and often circulated within specific social or professional circles. What do you notice about the text accompanying the portrait? Editor: It looks like an inscription. The words "Landammann und Bundespräsident" appear on the top, but they are challenging to make out. I wonder if it indicates some public office Heer held. Curator: Exactly. Knowing that Heer held such prominent positions changes our understanding, doesn't it? This is no mere portrait; it's a carefully constructed image intended to project authority and respectability. The choice of photography – a relatively new medium at the time – also signifies something. How might the then-novelty of photography contribute to this image? Editor: It possibly conveyed modernity. But there's a formal quality to the portrait itself – the suit, the beard, the way he looks directly at the viewer. Perhaps he wanted to convey an image of established authority, so photography was used to enhance the desired effect. Curator: Precisely. And that brings us to consider the role of photographic studios. They were key institutions in shaping the visual identities of individuals, particularly those in the public eye. Think about how these studios controlled lighting, posing, and even retouching to construct particular narratives. Editor: So, this photograph is not just a representation of Joachim Heer, but a product of social and institutional forces at play in that era. I never thought about photography that way! Curator: It’s about the public role of art and the politics of imagery. By exploring the historical and social context of an image, we discover new layers of meaning that simply aren’t visible on the surface. Editor: That makes you see that this object it much more than meets the eye. Thank you for sharing this point of view.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.