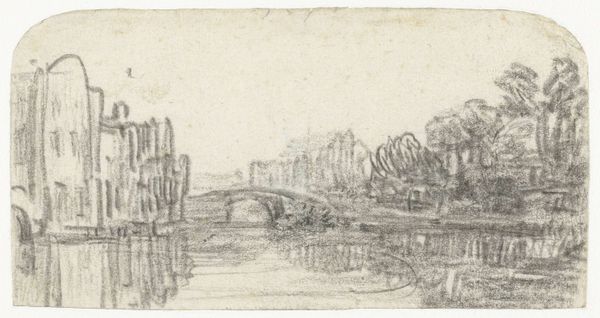

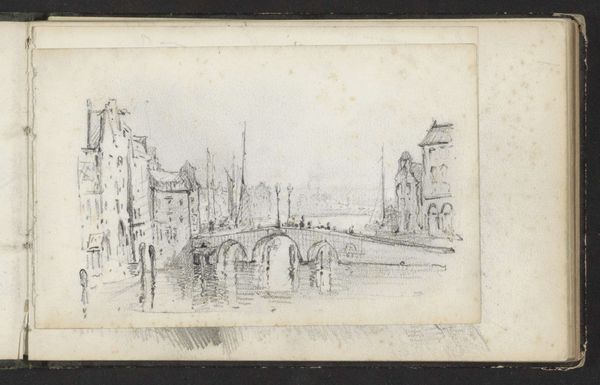

The Oude Haarlemmersluis (Old Haarlem Lock) on the Martelaarsgracht, Amsterdam c. 1638 - 1655

0:00

0:00

drawing, paper, ink, pencil

#

landscape illustration sketch

#

drawing

#

toned paper

#

dutch-golden-age

#

mechanical pen drawing

#

pen sketch

#

landscape

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pencil

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

cityscape

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

Dimensions: height 150 mm, width 193 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Jacob van Ruisdael's "The Oude Haarlemmersluis (Old Haarlem Lock) on the Martelaarsgracht, Amsterdam," dating from around 1638 to 1655. It's a drawing, mainly in ink on paper, and it has the delicate, almost ephemeral quality of a quick sketch. What captures your attention when you look at this? Curator: What immediately strikes me is the civic pride embedded within what appears to be a simple landscape. Amsterdam in the Golden Age was a hub of global trade and burgeoning capitalism. Drawings like this, showcasing infrastructure such as the lock, were visual affirmations of Amsterdam's power and control over its waterways, vital arteries for commerce. Consider who might have viewed this drawing - potential investors, civic leaders perhaps? Editor: So, it’s not just a pretty picture, but almost propaganda? Curator: I wouldn't jump to propaganda, but definitely a demonstration of civic virtue. The very act of documenting Amsterdam's infrastructure served a purpose. It reinforced the image of a well-ordered, prosperous, and modern city. Look at the way the bridge dominates the composition, the architectural details meticulously rendered. What message does that send? Editor: That they’re proud of it? Confident, even? It also shows the daily lives of the citizens. Curator: Precisely! Now consider where Ruisdael may have displayed or shared it. How did its likely audience inform its creation and lasting cultural importance? Editor: It's amazing how much context can be packed into what seems like a simple drawing. I'll definitely look at Dutch landscapes differently now. Curator: Indeed. Recognizing the cultural and political currents within an image deepens our understanding and appreciation, transforming our view of the art of the period.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.