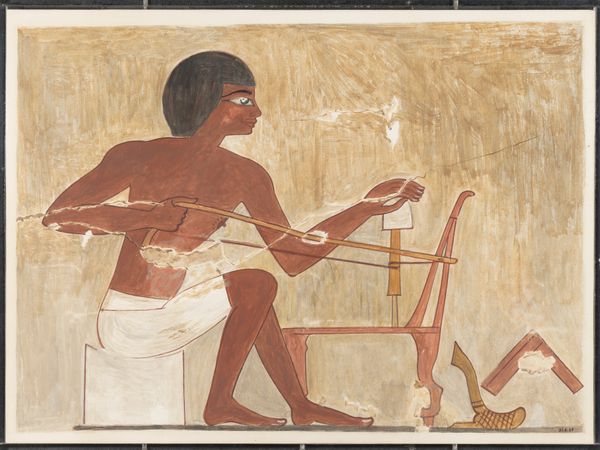

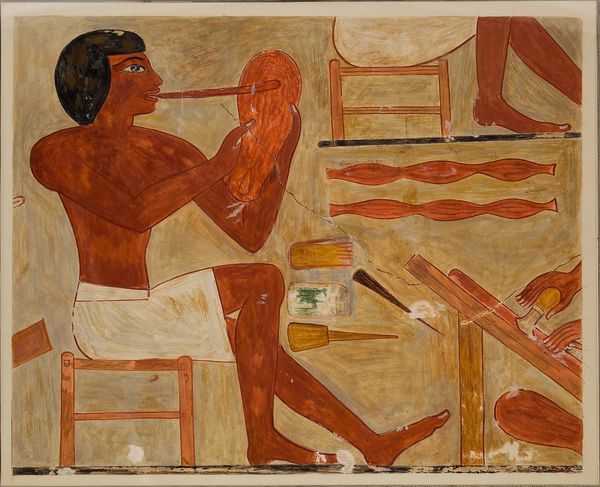

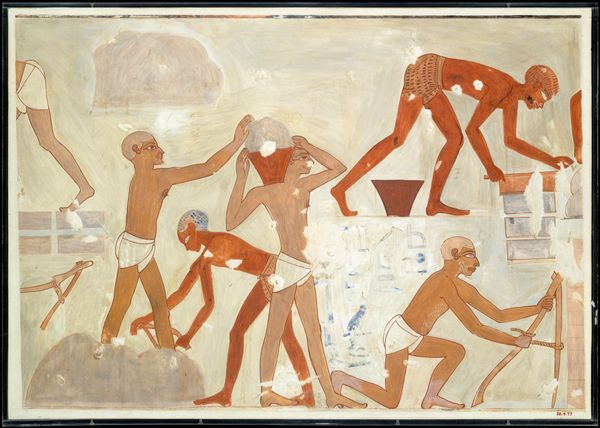

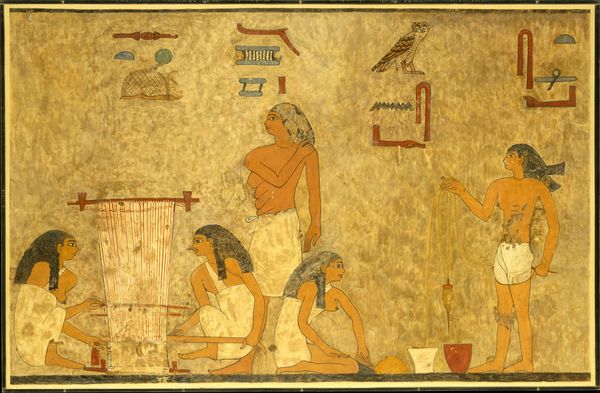

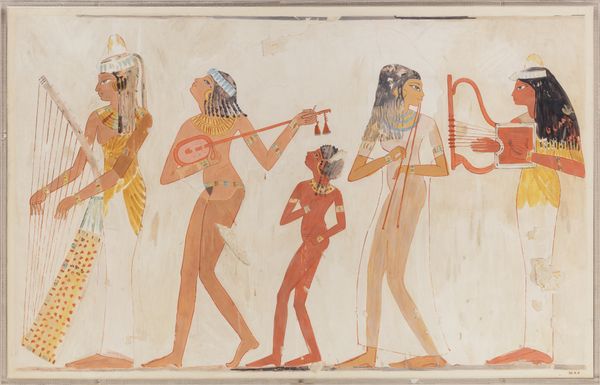

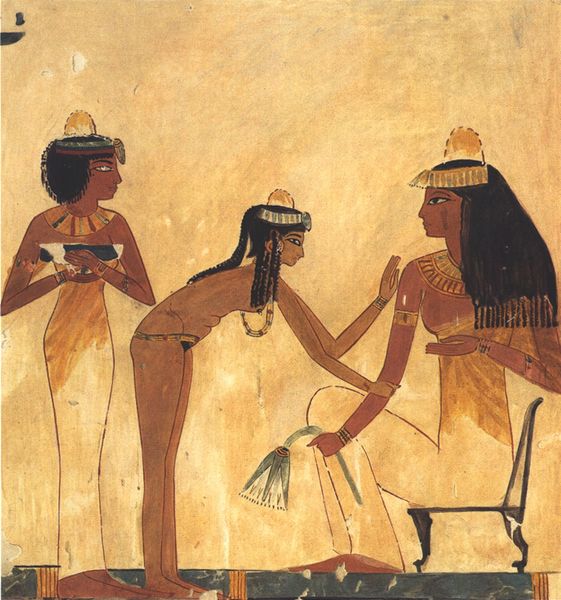

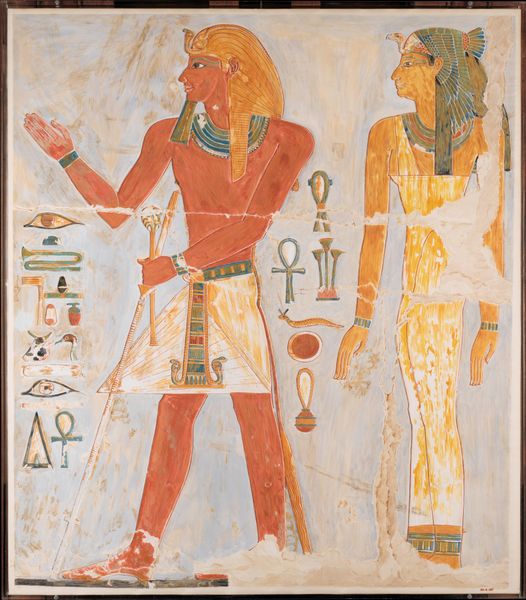

Stringing and Drilling Beads, Tomb of Rekhmire 1504 BC

0:00

0:00

painting, fresco

#

portrait

#

narrative-art

#

painting

#

ancient-egyptian-art

#

fresco

#

egypt

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

men

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

Dimensions: facsimile: h. 27.5 cm (10 13/16 in); w. 62.5 cm (24 5/8 in); scale 1:1 framed: h. 31.1 cm (12 1/4 in); w. 66 cm (26 in)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Welcome. We're standing before a reproduction of "Stringing and Drilling Beads, Tomb of Rekhmire," a fresco dating back to 1504 BC by Nina de Garis Davies. It offers an interesting glimpse into ancient Egyptian craftwork. Editor: My first impression is one of purposeful stillness. Despite depicting actions—stringing, drilling—the piece emanates a sense of calm, almost meditative concentration. It's quite striking given the context we can infer around labor in ancient societies. Curator: Absolutely. What draws the eye, formally, is the economy of line and the controlled palette. Notice how the artist uses ochre, brown, and white to define the figures and objects, set against a warm, neutral ground. This limited color scheme contributes significantly to the overall feeling of serenity. And the way the figures are positioned within the rectangular format provides stability, almost like pillars supporting the scene's narrative. Editor: The composition, though seemingly simple, is layered with meaning when we consider the social stratification of ancient Egypt. Labor like this—producing ornamental objects—was integral to the elite class maintaining its status and expressing power. Were these laborers enslaved, or skilled artisans? The image raises critical questions about ancient economics and workforce management. Curator: Yes, the image exists within a historical narrative. But even abstracting away its historical context, observe how the visual relationships generate meaning. The circularity of the beads echoes the continuous loop of the bow drill. Such internal rhyming is critical in conveying rhythm in an otherwise static image. The geometry grounds the experience. Editor: It also humanizes. Seeing artisans at work invites introspection about our own relationship to labor, our connections across time. What was it like to perform this tedious, repetitive task daily? Consider how contemporary production methods dehumanize workers, alienating us from process. Curator: Very interesting observation. These aesthetic qualities certainly resonate, even outside of their specific context. The piece reminds us about what lasts versus what changes when we talk about human conditions, expressed here in pigment on plaster. Editor: Agreed. Considering how it provokes inquiry, not only of history but contemporary working conditions, that staying power speaks volumes. A pertinent piece for this time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.