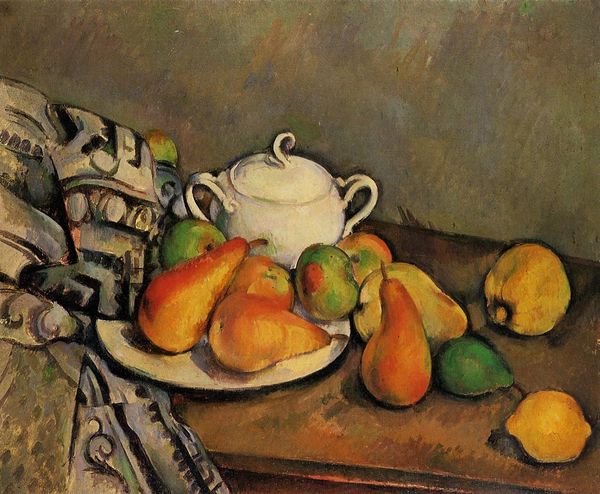

painting, oil-paint

#

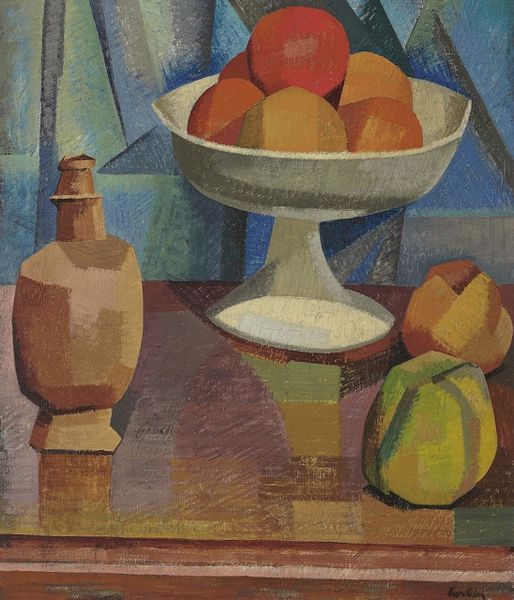

cubism

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

oil painting

#

fruit

#

geometric

Copyright: Public domain

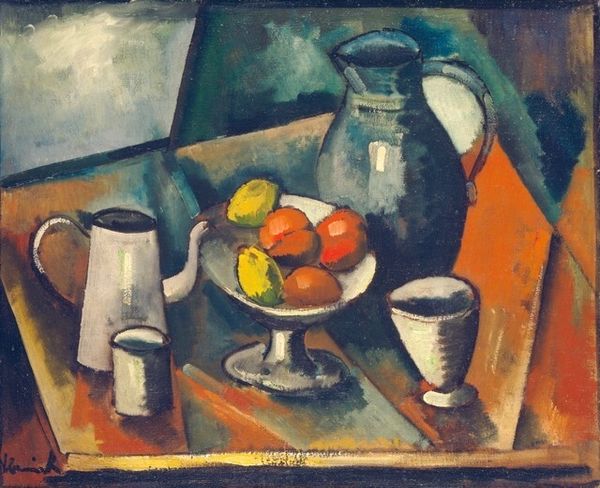

Editor: This is Roger de La Fresnaye's "Still Life with Coffee Pot and Melon" from 1911, an oil painting with a cubist aesthetic. I’m immediately struck by its somber mood; the browns and greys feel quite subdued. How do you interpret this work? Curator: The limited color palette and geometric forms are typical of early Cubism. Beyond aesthetics, consider the burgeoning Parisian art scene. There was a deliberate effort to break away from traditional academic painting, a move intrinsically linked to social and political upheaval. How does a still life become radical in this context? Editor: It’s… less about the objects themselves, maybe, and more about challenging established artistic conventions? Curator: Exactly. It questions the viewer's expectations and celebrates experimentation. The choice of domestic objects hints at bourgeois life but rendered through fragmented perspectives, it disrupts notions of stability. Does this fragmentation mirror a wider societal anxiety about a rapidly changing world? Editor: It definitely adds another layer. So, what seems like a simple still life becomes a reflection of societal tensions of its time, seen through an art world lens that questions power structures? Curator: Precisely. And remember the art market itself—the shift towards dealers and collectors empowered these artistic explorations. The public role of art was being redefined, as well as how these objects gain cultural capital. Editor: I see. I originally just thought of it as an interesting arrangement of objects, but understanding the art world and the socio-political conditions really deepens the interpretation. Curator: Indeed, this allows a glimpse into the broader historical currents shaping artistic production and reception. The artist makes it, the institution frames it, and we give it value and new interpretations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.