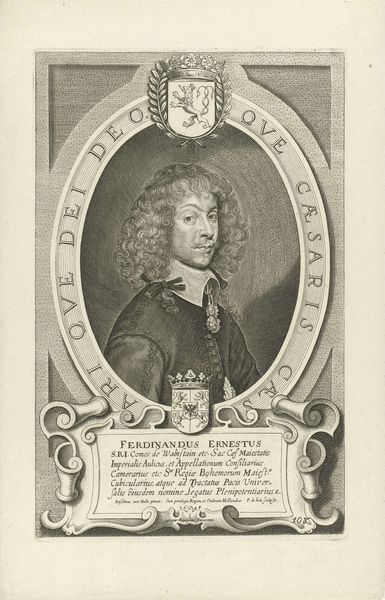

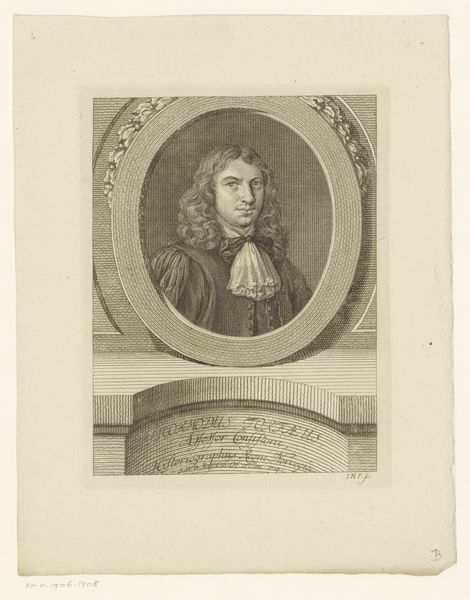

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 175 mm, width 128 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Ah, a striking print. Here we have Matthäus Merian the Younger's 1652 engraving, a portrait of Ferdinand Ernst, Count von Waldstein. What do you make of him? Editor: Intense! The Count definitely wants you to know he's important. The fineness of the engraving emphasizes all that meticulous detail, from the texture of his hair to the embellishments on his coat, projecting both wealth and a carefully crafted image. You can tell this piece took skill and labor to make. Curator: It's remarkable how much information Merian conveys. Waldstein was a significant figure, deeply involved in the political landscape of the time. His formal attire, isn't it quite representative of the Baroque era's taste for display? It gives the artwork a grandiose feeling! Editor: Absolutely! Engravings like this were basically early PR, shaping public perception. Notice the inscription below—all those titles packed into one frame; clearly designed to impress, to signify power, and perhaps more broadly, a commentary on status and what it meant materially in the 17th century. And the oval frame within a rectangular page makes it look like one object placed on the surface of another. Curator: Indeed. And the level of detail attained solely through incising lines—consider the time invested, the precise movements required. Do you believe the intention was to glorify, or just a depiction for historical record? Editor: Both, probably! It served as a promotional tool, but also as a document, showcasing a powerful individual, in the moment. We shouldn't overlook the function of engravings as essentially multiples—part of the machinery of early modern circulation. The engraving medium itself is designed for dispersal, for broader consumption! Curator: I'm reminded of how such works, beyond being mere images, offered access to the likeness of powerful figures, especially useful as tools to create social connections or demonstrate a connection of some sort. Editor: And for a cost—some more readily available than a commissioned oil painting, of course. They tell stories about production as well as power dynamics. Curator: Reflecting on the piece, I'm impressed anew by the craft required. It makes me appreciate what engraving offered its own era, one that allowed portraits to be captured into printed, repeatable image, the sort you see over and over again, just like today. Editor: True! These works hold such cultural echoes in the materiality. Next time you see someone who looks "old fashioned", maybe it will be easier to tell whether they would prefer a portrait made of themselves—or a selfie!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.