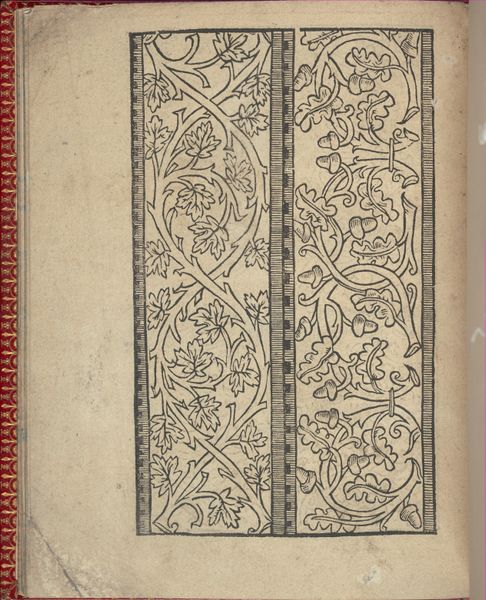

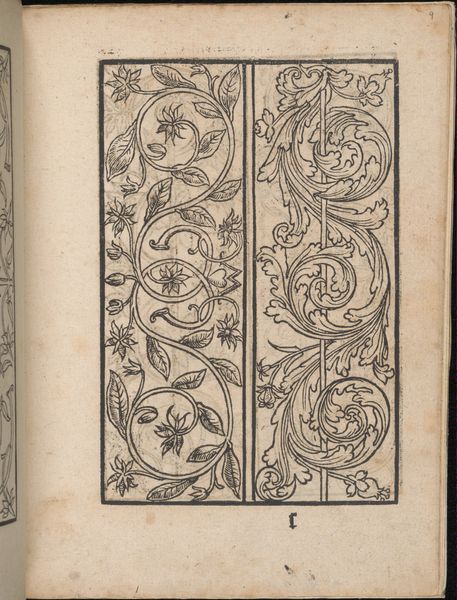

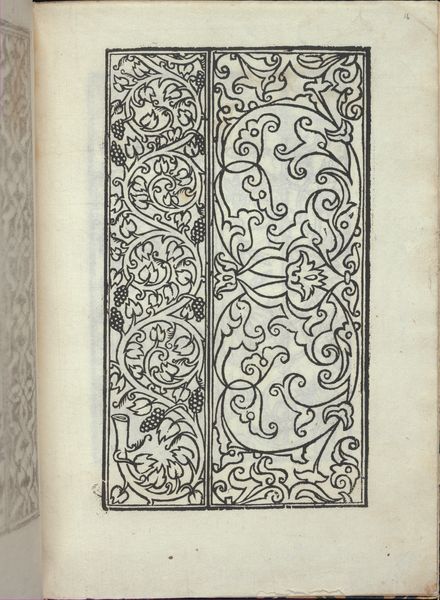

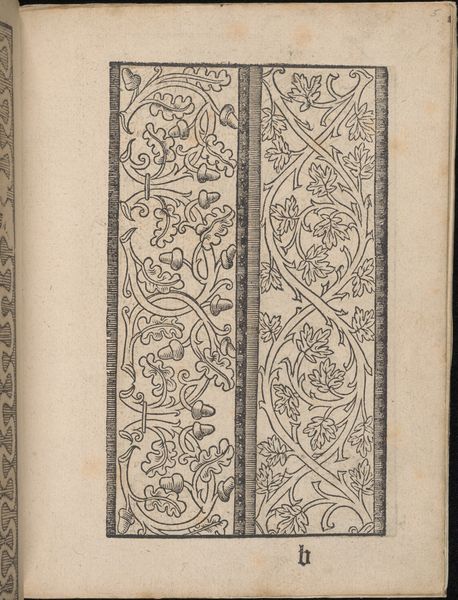

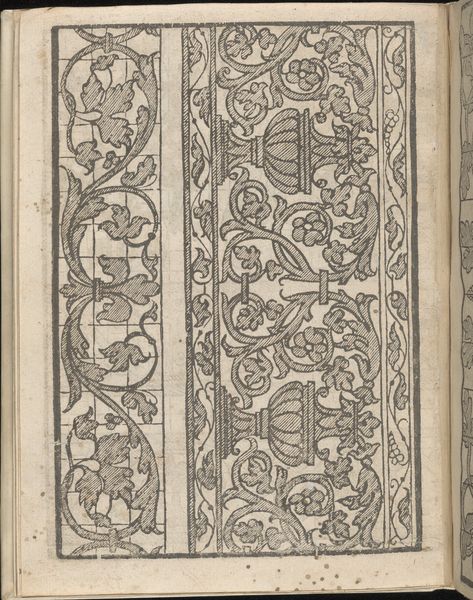

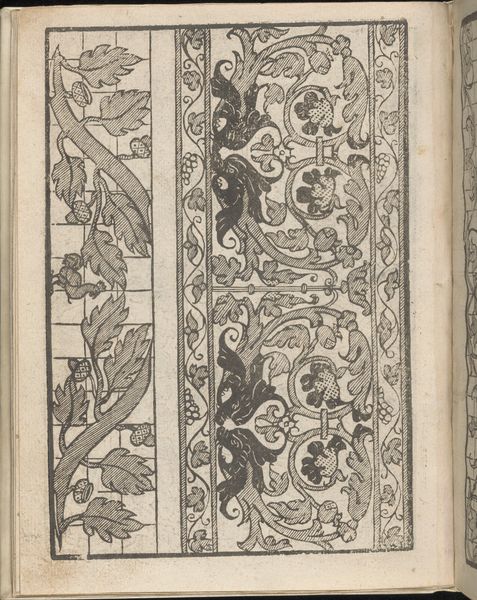

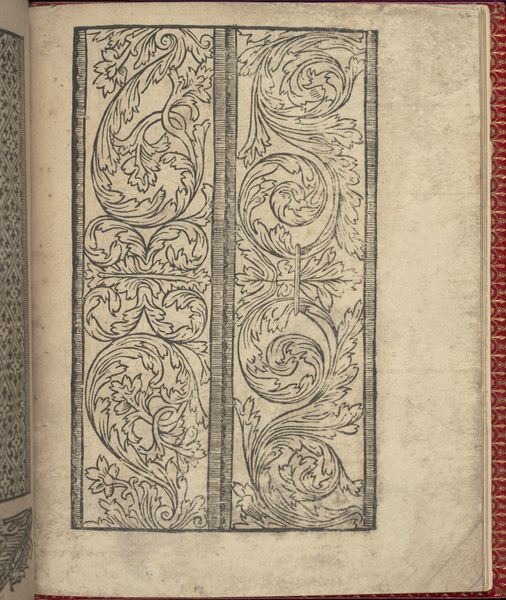

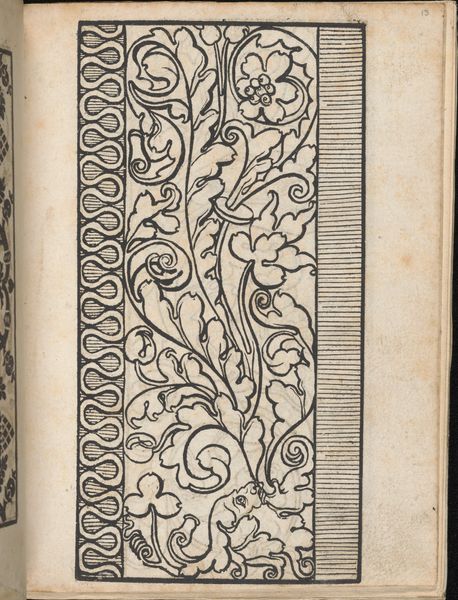

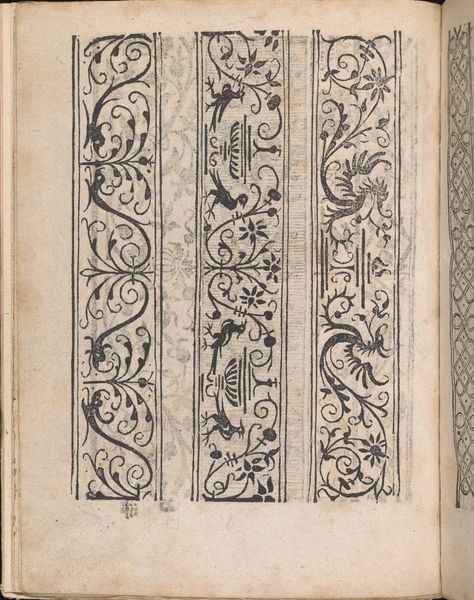

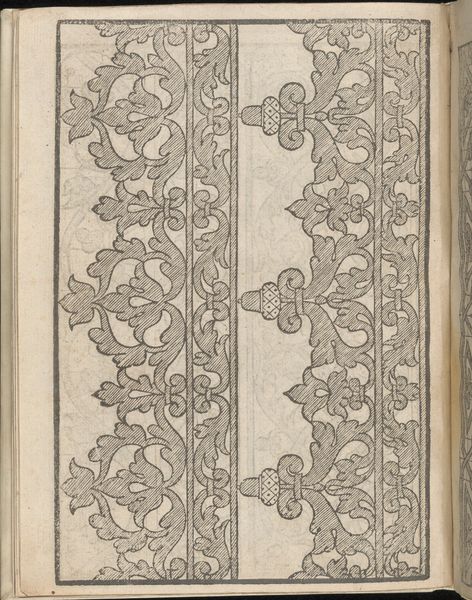

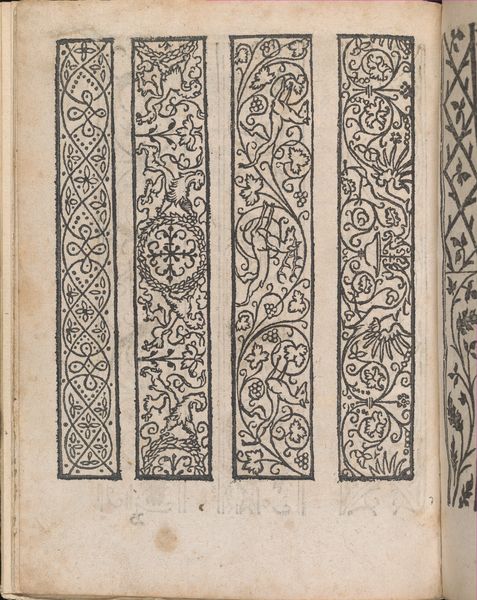

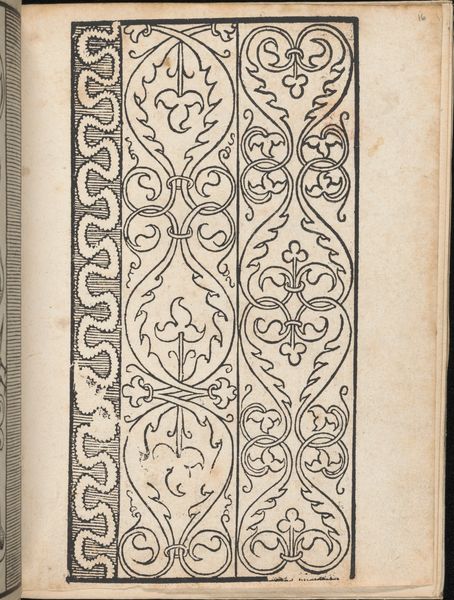

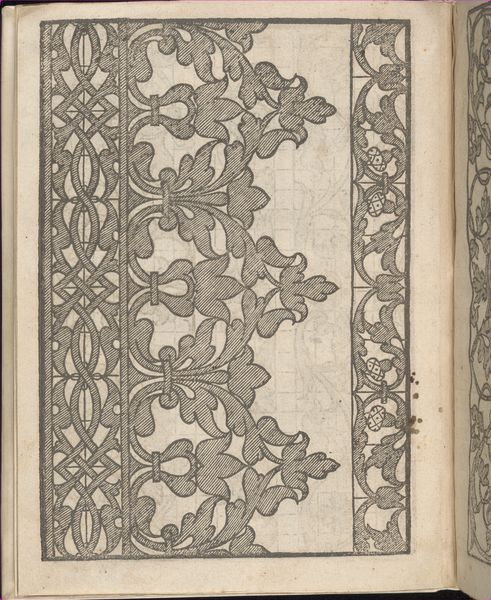

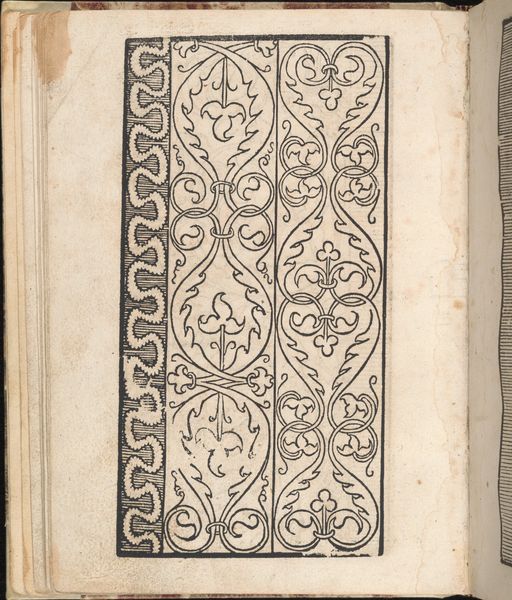

drawing, print, woodcut

#

drawing

# print

#

book

#

11_renaissance

#

geometric

#

woodcut

#

line

Dimensions: Overall: 7 7/8 x 5 1/2 in. (20 x 14 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Looking at "Eyn new kunstlichboich, page 4r," a woodcut printed in 1529 by Peter Quentel, what captures your eye? It is currently part of the collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: Immediately, it's the formality. There’s a rigid symmetry fighting against the organic, flowing leaf patterns. It’s like nature trying to break free from imposed structures. Curator: Yes, those structured yet ornamental borders contain mirrored patterns that suggest duality, a prevalent Renaissance motif of order versus nature, reason versus emotion. This book served as a model for artisans, offering templates that reveal a particular visual culture of that time. What visual echoes do you perceive? Editor: I see resistance here—subversion in seemingly innocent designs. This was the period of the Reformation; the imposition of structure reflects the existing societal power and expectations. Curator: And yet the tendrils, the foliage—they still curl and reach. In symbolism, the repeated motifs have meaning. For instance, many see acanthus leaves symbolizing immortality or rebirth—the ever-renewing aspects of existence itself. The pattern is literally embedded cultural meaning, but maybe something deeper. Editor: The material itself speaks too. The sharp lines cut from wood. Woodcuts as a form were democratized printing– accessible—they gave more access to pattern and image, like recipes of power. To me the symbolic tension arises from its wider audience and the tension with high status of its motifs. What kind of freedom, creative, economic or even spiritual did the pattern offer to its maker and to its viewers at this critical juncture? Curator: I like how you see that. Consider the context too: this manual aided crafts people in adorning domestic objects. It was part of weaving iconography and aesthetic language into daily lives, extending values into tangible forms. What stories, conscious and subconscious, would this artwork help construct in the world? Editor: It underscores how art never exists in a vacuum. These "craft recipes" mediated social class, gender, the individual to greater questions about art and freedom in periods of immense change. Ultimately it's not only a testament of craft and beauty, it stands in the tensions of that historical period, questioning identity and creativity. Curator: Indeed. Studying historical handbooks like this truly shows art's entwined relationship with the cultures it reflects. A pattern is never just a pattern.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.