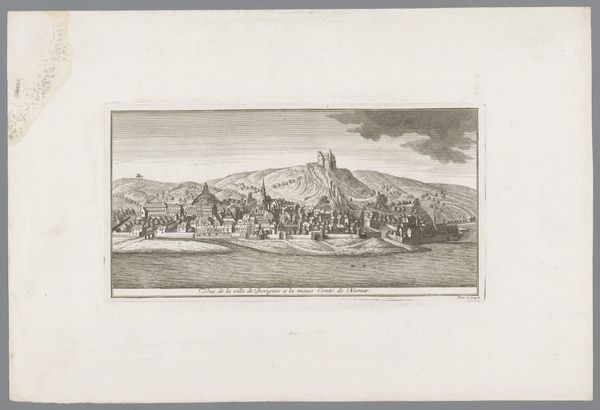

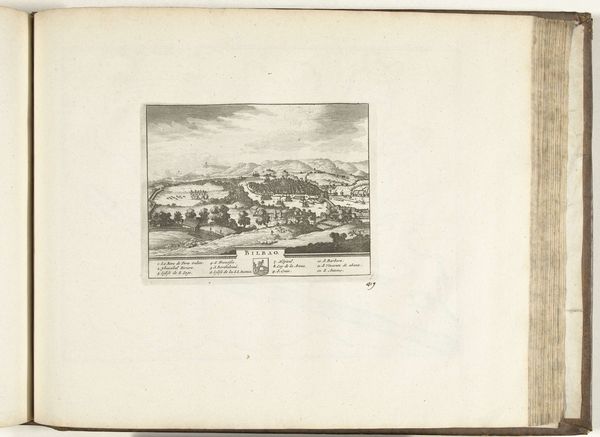

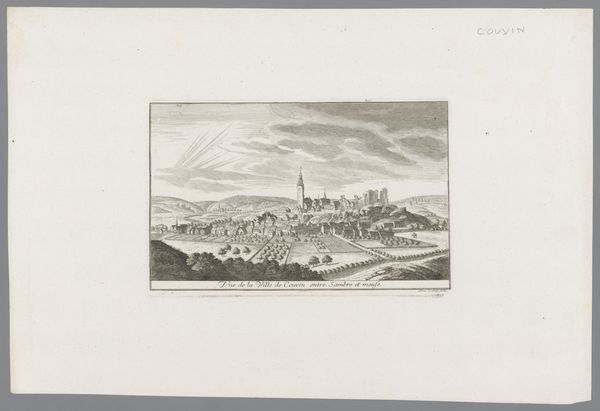

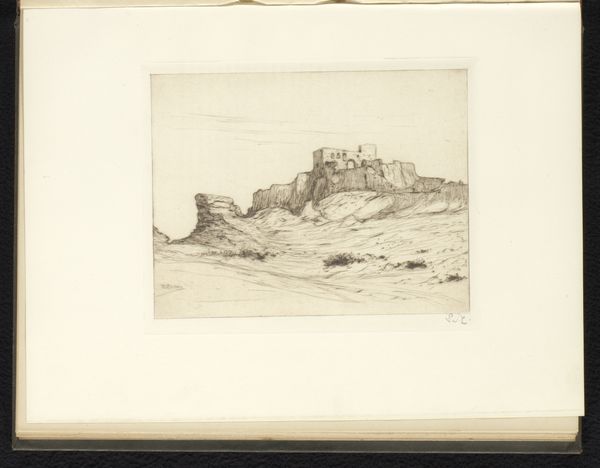

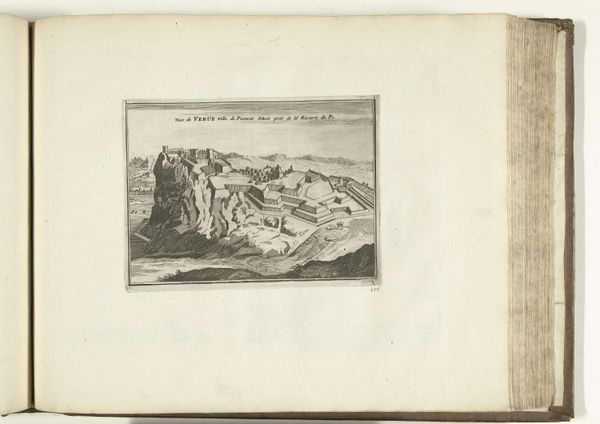

print, paper, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

paper

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 140 mm, width 215 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

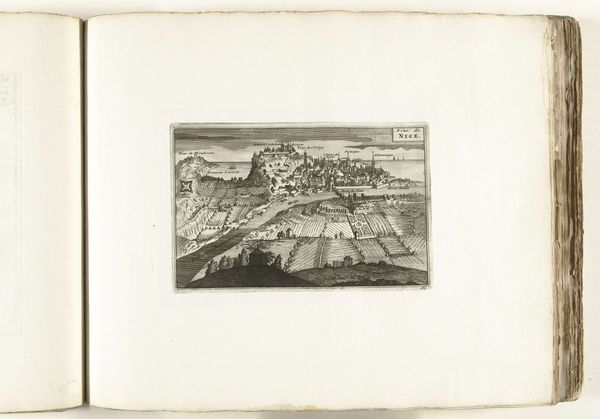

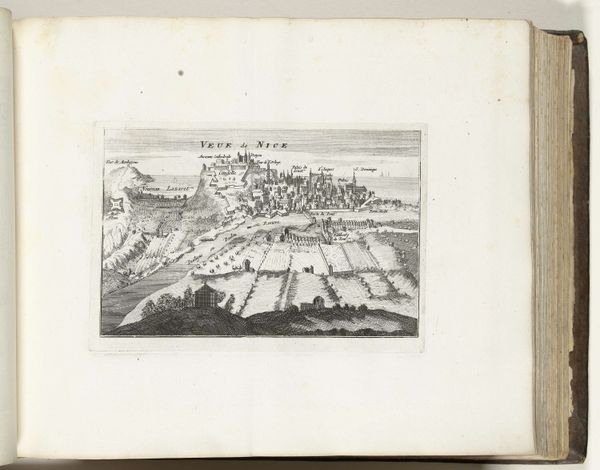

Curator: This delicate engraving, dating from 1726, offers a panoramic view of Nice. Created by an anonymous artist, the piece is simply titled "Gezicht op Nice, 1726", which translates to "View of Nice, 1726." Editor: My first impression is of an idealized serenity. The precise lines and elevated perspective present Nice as an ordered, almost idyllic space. Everything seems meticulously placed, neat and orderly. Curator: That sense of order is very characteristic of Baroque aesthetics, and cityscapes in this era served very specific social functions. Engravings like this weren't merely records; they were assertions of power and civic pride. This piece captures Nice at a pivotal point in its development. Editor: You're right, there’s definitely an element of curated control in this image. But what I find striking are the repetitive patterns -- the rows of crops and the meticulously rendered buildings all feel very controlled, which resonates as much psychological as it does political, it almost has a symbolic intention in terms of an individual’s role within a town or even a city. Curator: The composition directs the eye carefully, encouraging a specific reading of the city’s social space, wouldn’t you say? I wonder about the implications of this constructed viewing experience, as well. Does it limit understanding in some way? Editor: I suppose it’s a kind of flattening—the lives and dramas that would inevitably be happening are smoothed over for this idealized version. You almost feel a lack of movement throughout. Curator: The rigid visual language may even be reinforcing those specific roles. Looking closely at the symbolic content of art helps us access some of the subtle social codes of the time period. It offers access to cultural memory and collective emotion in really meaningful ways. Editor: Precisely. This seemingly simple landscape tells us as much about how the city *wanted* to be seen, and the social conditions they operated under, as it does about its actual appearance. I’m struck at how such images offer a portal to understanding broader patterns within a community, even hundreds of years later.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.