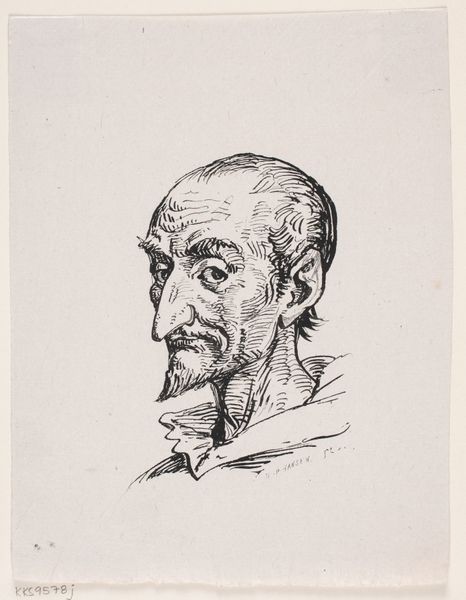

drawing, print, etching, paper, ink

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

etching

#

paper

#

ink

#

portrait drawing

Dimensions: 150 × 125 mm (image/plate); 158 × 130 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Isn't this portrait by Rembrandt, entitled "The First Oriental Head," just magnetic? I'm completely drawn in! It's an etching dating back to 1635. You can see it currently on display here at The Art Institute of Chicago. What are your immediate impressions? Editor: It's got a certain gravitas, doesn't it? All those lines digging into the paper; they speak of wisdom etched by time and experience, though perhaps a touch world-weary. What do you make of the ‘Oriental Head’ designation? Curator: Right? The detail for such a relatively small piece is mind-blowing. You can see every crinkle around his eyes! I find the name slightly puzzling, actually. Today, the term "oriental" is considered antiquated, and in the context of 17th-century Dutch art, it speaks volumes about the contemporary European understanding – or misunderstanding – of the "East." The exoticization, right? It's clearly not just a neutral descriptor. It really sparks a question, what kind of story did Rembrandt wish to weave around the portrayed person. Editor: It does highlight that power dynamic. Maybe it isn't a simple record of appearance, but an early modern construction of identity, using clothes and accessories to present a specific "Eastern" figure for a European audience, very powerful, as these images, symbols, even stereotypes linger in our collective consciousness for centuries. Curator: It's precisely that tension I love! On the one hand, the sheer skill with which Rembrandt renders the face gives this figure a kind of eternal, individualized humanity. On the other, the title anchors him to a specific, and somewhat stereotyped, category. That juxtaposition… it forces you to look closer, think deeper about how we see, classify, and maybe, misinterpret others. What do you make of the fur mantle and chain, what do you see beyond mere orientalism? Editor: They’re markers of status. A kind of stage dressing—but this figure remains enigmatic despite such clues. It’s fascinating how an image from so long ago can still prompt so many questions about representation and identity even today. Perhaps the 'Oriental Head' is more of a mirror, reflecting the perceptions of Rembrandt's time back at us. It asks as much about who is watching the portrait as it does about the subject being watched. Curator: Definitely. And that’s where the continued power of Rembrandt resides. Even when his titles feel a little off-key, his artistry tunes us into the deeper questions about ourselves and the world around us. It leaves an echo, long after we've walked away. Editor: A contemplative, sometimes unsettling echo of historical curiosity and artistic reflection, all condensed into a deceptively simple-seeming portrait.

Comments

rijksmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

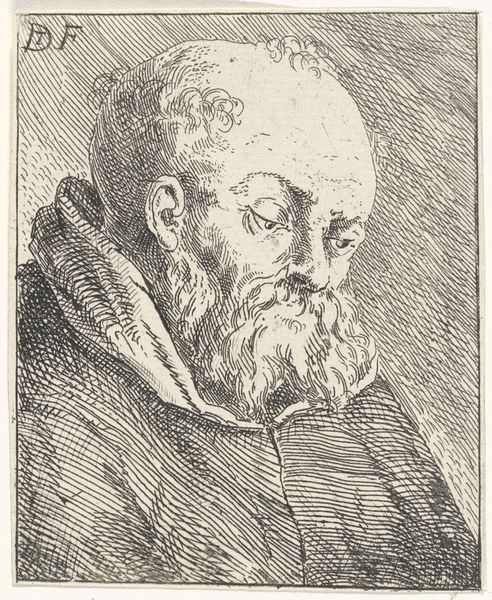

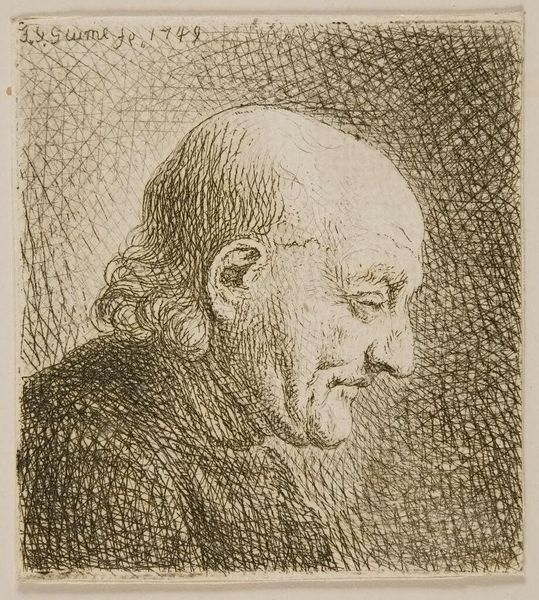

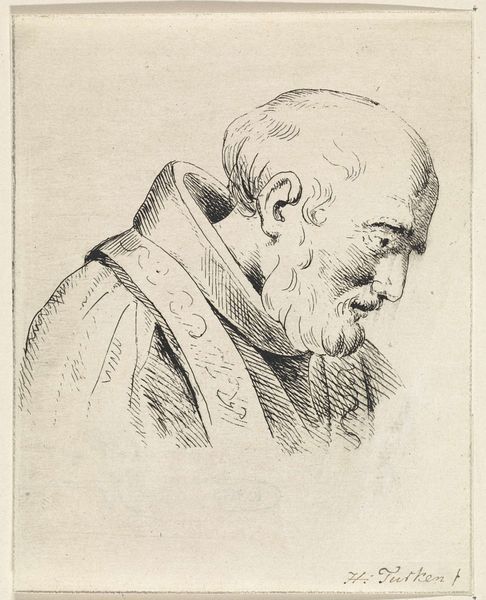

This set of etchings is traditionally called the ‘Four Oriental Heads’. Rembrandt did not etch them from life, but rather after prints his Leiden friend and colleague Jan Lievens made around 1631. He did not do this simply because he admired Lievens’s work. On three of the four prints, Rembrandt noted that he had geretuckeerd (meaning both adapted and improved) them.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.