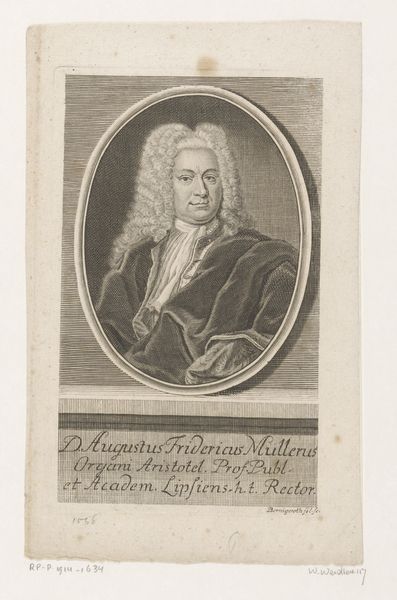

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 162 mm, width 100 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

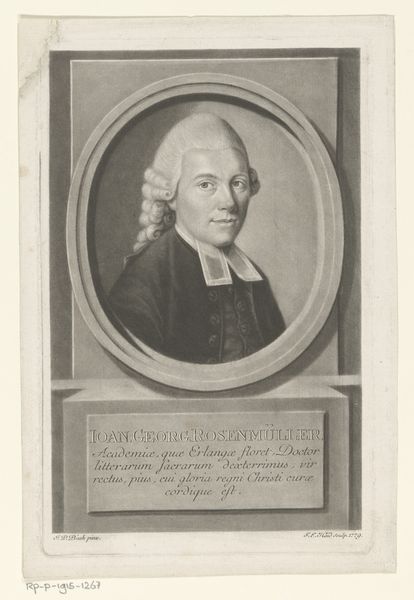

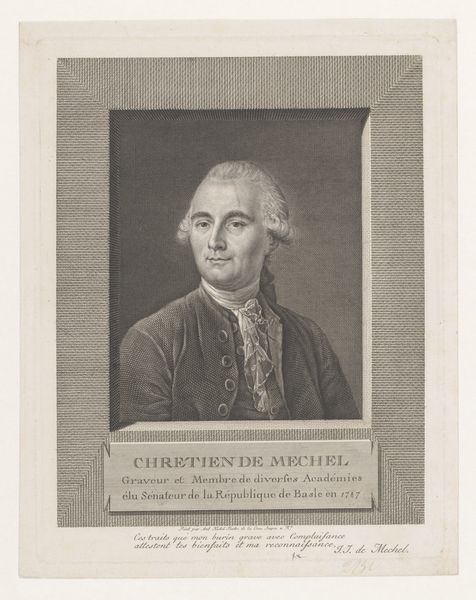

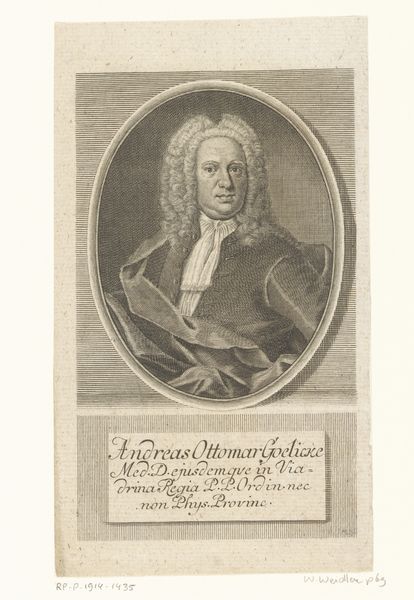

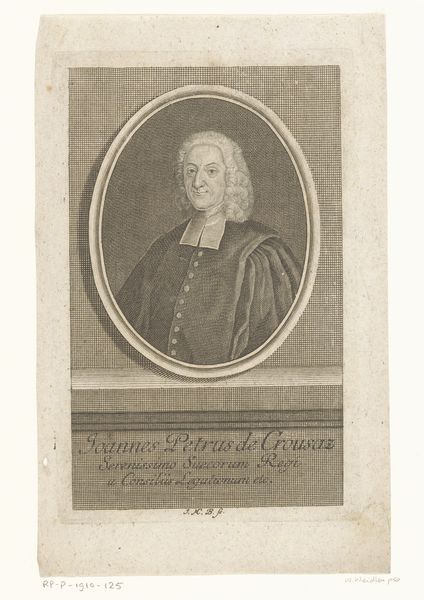

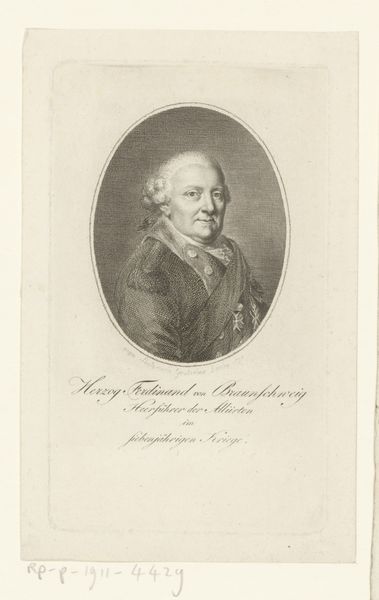

Curator: Here we have Johann Martin Bernigeroth's "Portret van Christian Eberhard Weißmann," created in 1744. The print, executed with meticulous engraving, is currently held at the Rijksmuseum. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by the formality, the way it seems designed to reinforce a very particular image of power and learnedness. He looks almost…wig-like. And who decides what is an acceptable portrait for which social circles? Curator: The wig is definitely part of that intended persona. Weissmann was a Doctor of Theology and professor in academia, as is explained in Latin below his likeness. Think about the institutional power and self-fashioning embedded in formal portraiture of the period and this social echelon. Editor: Absolutely. It speaks volumes about access, right? Who had the privilege of representation like this? Weissmann clearly wielded cultural capital; the portrait's creation and dissemination reinforced his position. It makes me consider whose stories remain untold, whose images are unseen in institutions like this. The engraving emphasizes not just wealth but belonging in the intellectual circles that define eighteenth-century Europe. Curator: Precisely. The very act of commissioning and then reproducing this image – the print form making it available more widely - was a statement. I would also mention its creation and preservation, and that Bernigeroth created multiple portraits of academic figures: it speaks to a community but it is also a product. Consider it within the broader context of patronage and the relationship between artist and sitter in this period. This dynamic also determines which individuals and stories become memorialized and canonized. Editor: The attention to detail, the texture of the fabric… It’s interesting how Bernigeroth uses a reproducible medium like printmaking to convey such status and apparent realism, however idealized. Is he, through the act of producing prints, making visible an inherently discriminatory system? I am unsure he realized he was documenting an academic power structure based upon class. Curator: That's the compelling question isn't it? This isn’t merely a historical relic, it’s a powerful tool for interrogating the legacy of power, knowledge, and representation. Thanks to Bernigeroth, we have the chance to do it. Editor: I agree. It serves as a reminder of both who was visible and, more importantly, who was not in the creation of historical narratives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.