#

portrait

#

water colours

#

watercolor

Dimensions: overall: 47.2 x 63.2 cm (18 9/16 x 24 7/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

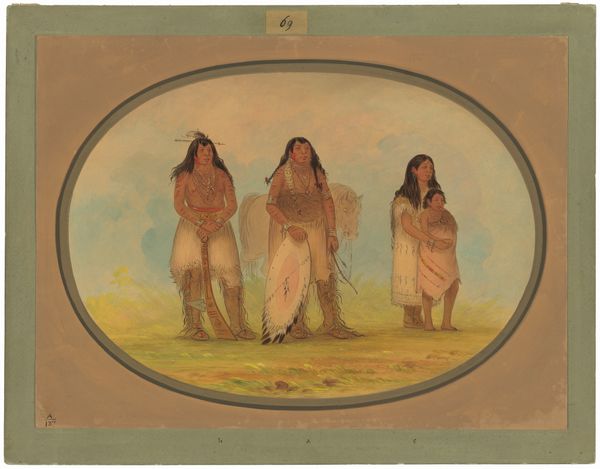

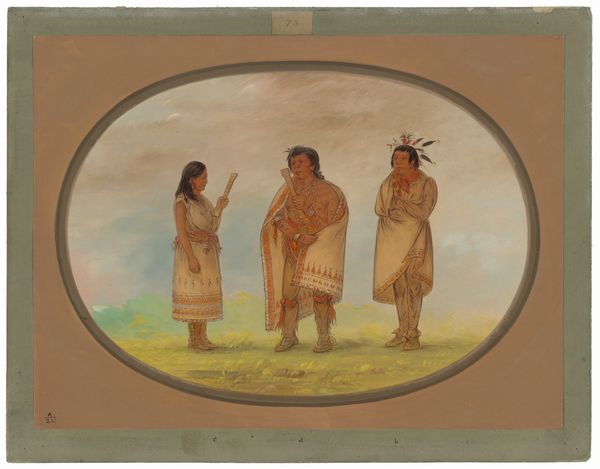

Curator: Standing before us is "A Cheyenne Chief, His Wife, and a Medicine Man," a watercolor created by George Catlin between 1861 and 1869. What’s your initial reaction? Editor: Well, there's a serenity, almost a sadness in the piece. The pale watercolor tones, the way the figures are presented so frontally… it feels like a quiet observation. There's a simplicity that draws me in, but it's hard to ignore the colonial context of the artist capturing Indigenous life. Curator: Absolutely. I'm captivated by the Chief's regalia – the bear claw necklace and that striking feathered headdress. It whispers tales of power and ceremony. Editor: Indeed. And consider Catlin's work within a broader history of image-making that frequently exoticized and objectified Indigenous people. I see this not only as portraiture, but as a complicated cultural document, tinged by the Western gaze, but possibly offering glimpses of lived experiences, resistance, and cultural endurance. I would want to understand much more about the dynamics and possible power dynamics when Catlin created the image. Curator: I find that a balanced view. What’s fascinating, too, is the medicine man playing the flute. It injects a moment of performance, of cultural expression, but the whole scene still carries this aura of observation. What I read as a beautiful instrument could be interpreted by others very differently, depending on perspective. Editor: The narrative aspects – like that detail of the flute, and how each is carefully presented – clash with the historical implications. I keep asking myself who the intended audience would have been for these artworks, and how the images served political purposes at the time. Curator: It definitely demands interrogation. Still, when you allow yourself to linger with it a moment, you sense respect, possibly born out of genuine encounters? Editor: It’s a visual conversation, indeed. It requires historical empathy, an awareness of context, and a critical eye toward the artist's intentions. To grapple with images from the past is never straightforward, but it opens invaluable spaces for dialogue and change. Curator: So true! And maybe this image isn’t an endpoint but an invitation into ongoing discussions and further discovery?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.