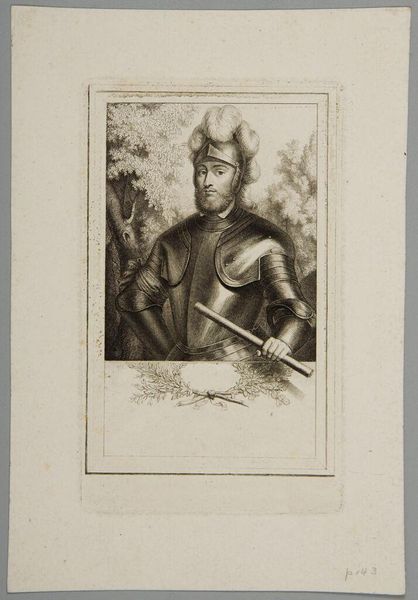

drawing, print, graphite, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

pencil drawing

#

graphite

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

graphite

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 402 mm, width 296 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Look at this portrait! The sharp graphite lines forming Dirk IV, Count of Holland. Made around 1650 by Cornelis Visscher, it resides here at the Rijksmuseum. It really leaps out. Editor: Yes, the materiality is remarkable. Look at the quality of the print. You can see the dense layers and variations in tone, evidence of the artist’s labor with graphite and engraving to produce something of such intricacy. There's something quite stunning in its almost photorealistic quality. Curator: Absolutely! Consider that Dirk IV died in 1049. So Visscher created this image over six centuries later, contributing to the already-loaded symbolism of Dutch identity and statehood. He isn't merely depicting a man; he's reinforcing a constructed lineage and solidifying historical narrative during a time of intense political development within the Netherlands. Editor: And thinking about it materially, what were the circumstances that determined this need for such visual reinforcement? The consumption of prints such as these must have been shaped by the material conditions and needs of that era. Perhaps cheaper and faster to reproduce compared to a painting on canvas? It could be the choice of accessibility and a reach toward broader audiences beyond elite spheres. Curator: That’s right. The very creation and circulation of such portraits serve as an act of enshrining specific individuals and a larger idea. It highlights the dynamics of power, particularly relevant given Holland’s evolving role. Editor: And we shouldn’t dismiss how the craft aspect speaks volumes. There is no singular piece, no virtuoso brushstroke; it is an etching and engraving – something born from labor and replication. Each stage impacts and expands meaning. The physical marks left, the transfer of the image itself and its multiple uses all speak to a broader meaning, in my eyes. Curator: Yes. Beyond just seeing an image of power, we also feel how power manufactures meaning across centuries. By understanding the portrait not as a singular representation, but rather as one drop within an ocean of portrayals. We start realizing the deeper politics at play. Editor: This reframes how we see historical representation. Considering art-making as social action and a chain of events allows new insights into consumption. Curator: Exactly, each one brings forth questions regarding the circulation of ideals and societal constructions. Editor: Right. When you think about all that handcraft. Extraordinary. Curator: It definitely brings new perspective.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.