Dimensions: height 87 mm, width 53 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

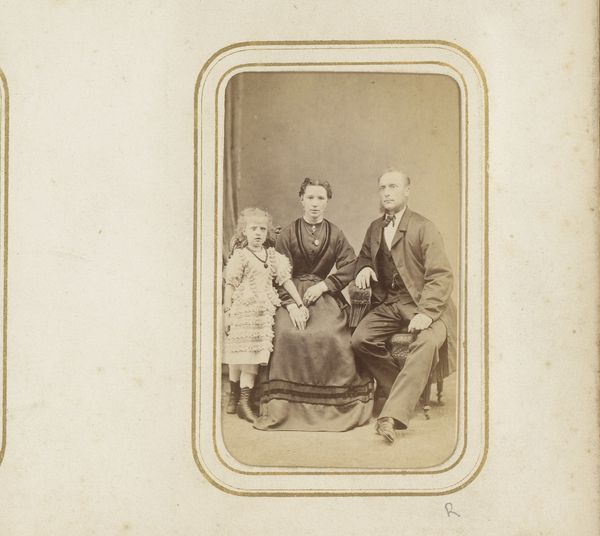

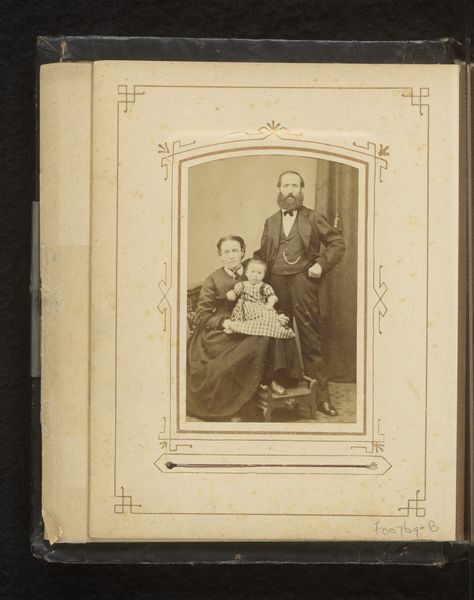

Curator: This gelatin-silver print, titled "Portret van een man, een vrouw en een baby," dates from between 1860 and 1900. There's such an endearing quality to the domesticity it conveys. Editor: My first thought is how dark and serious it feels. The stark contrasts, the heavy clothing—there’s a tangible weight to it. You can almost feel the starch in their formal garments. Curator: Starch, yes, a fascinating choice of words! It brings to mind the rigidity of societal expectations, especially regarding family. The father's intense beard symbolizes patriarchal authority, doesn’t it? A mark of virility and societal status. Editor: Well, beyond the symbolic read, consider the practical aspects. Those elaborate clothes weren't mass-produced; they were made by someone, probably multiple someones, involving considerable labour. You can bet there are a whole array of materials in play here, not just silver. Curator: I am certain. The clothing evokes a Victorian-era symbolism. Notice the mother's elaborate dress. Even if the subjects' economic standing cannot be verified from just looking, the careful costuming serves the semiotics of bourgeois sensibility. Editor: Semiotics aside, think of the photographer and their process. Gelatin-silver prints involved a chemical dance – light, silver, gelatin—creating an object intended for display and likely duplication. These kinds of techniques meant these images could move beyond the individual owner. Curator: A family photograph becomes a document of familial lineage! Indeed, it's not just an image, but a tangible relic. I wonder about the story behind their expressions: anxiety? Resignation? They clearly invested in immortalizing this moment, a tableau of early family life. Editor: It's precisely that interplay between intent, material reality, and societal framework that makes it such a compelling artifact, in my view. Understanding production illuminates broader trends, while of course your insight reminds us that people looked very different at this time! Curator: Precisely! Considering how it functions as both family memento and a cultural symbol broadens one's understanding of nineteenth-century photographic traditions. Editor: I think that both its immediate impact, and material existence offers an exciting entry into that moment's understanding of the family unit.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.