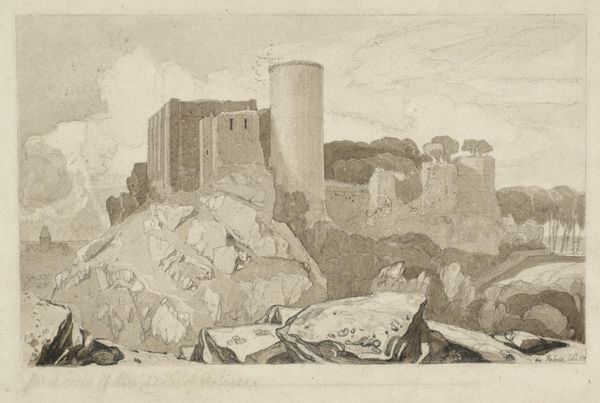

Dimensions: height 233 mm, width 325 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Martinus Antonius Kuytenbrouwer Jr.'s etching from 1854, "Ruïne van het kasteel van Beaufort," housed at the Rijksmuseum. It strikes me with a real sense of stillness; what can you tell me about it? Curator: What I see is the intersection of artistic skill, industrial production, and the consumption of romanticized ruins. Consider the etching process itself. Acid biting into metal—a controlled chemical labor producing reproducible images. How does the print medium democratize access to such scenes? Editor: I guess it means more people could own a copy. But what about the scene itself? It looks like it glorifies the past. Curator: Precisely. The crumbling castle is a product of history, war, and decay, but its depiction is carefully crafted and disseminated. The line work, a form of industrialized craft, becomes a commodity appealing to a market eager for romanticized landscapes. How does this etching participate in the social construction of 'the ruin' as a desirable aesthetic object? Editor: So you are saying that this etching isn't just a pretty picture, but a product of its time, influenced by the methods of production and who wanted to buy it? Curator: Absolutely. The choice of materials—the paper, the ink, the metal plate—and the labor involved are inseparable from its meaning. Think of the etching not just as an image, but as an object circulating within a network of economic and social relations. What does this make you consider? Editor: I see. It is all about considering who is producing it, how they're doing it, and why someone would want to buy it, not just about the romanticism that it shows. Thank you. Curator: Indeed, viewing art through its means of creation opens up deeper understanding. It makes us see beyond the image, to the process, its people, and materials.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.