#

light pencil work

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

incomplete sketchy

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

sketchbook drawing

#

sketchbook art

#

initial sketch

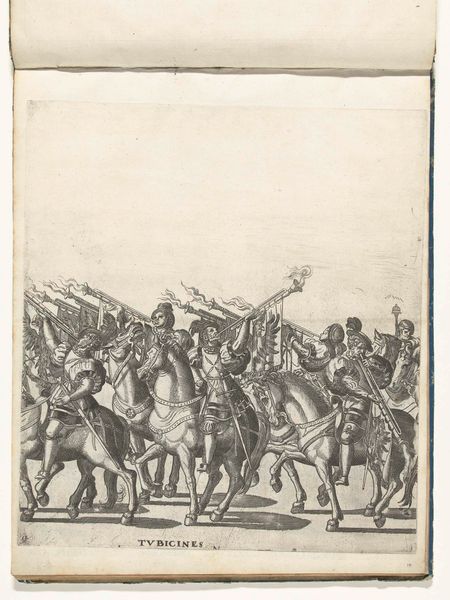

Dimensions: height 620 mm, width 1228 mm, height 778 mm, width 1496 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Aureliano Milani’s "Kruisdraging," a pen and ink sketch from 1725. The scene is teeming with figures. Editor: The sheer number of figures makes it feel…claustrophobic. Almost unbearably so. Is that the intention, do you think? To convey the mental weight, through a heavy visual weight? Curator: Possibly. Consider the artistic production in 1725; what was prioritized, how easily these images were made and circulated, by whom, and for whom. Pen and ink sketches, like this one, provided artists with opportunities for experimentation in a portable, readily accessible format. Think of this less as the end-point and more of the preparatory process for other, potentially larger works, or as an exploration in narrative building. Editor: Narrative building is a great point to mention in relation to this sketch; note how the artist draws your eye toward the figure of Christ struggling with the cross. It is a powerful symbol that reverberates throughout art history. Do you see how he uses subtle tonal shifts, too? It's darker around Christ, and in this manner, Milani isolates the suffering figure but also visually prepares viewers to recognize Him. Curator: And observe the lines themselves, creating areas of light and shadow with rapid, repeated strokes. This process seems focused on exploring composition, testing what details convey weight, physical strain, versus where details can recede, to show architectural settings. The choice of a sketch in pen and ink lends immediacy; how it speaks to the relative ease with which it could have been produced compared to, say, painting a massive altarpiece on canvas. Editor: Note also how the Roman soldiers appear rather unsympathetic; some seem almost amused, heightening the cruelty of the moment and its timeless quality as the struggle against injustice repeats itself across cultures. The architecture, too; do you think that was intended to imply a more specific time, locale, and political system? Curator: I think you're spot on. And what I take away most is a heightened sense of the material conditions for such works: the relative ease, portability, as contrasted against its potential use to generate future work in an ongoing exploration of ideas and methods. Editor: I will definitely think differently now about how these early sketches, imbued as they were with so much symbolism, functioned to inspire emotion for viewers both then, and now. Thank you for those useful comments about production, by the way!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.