Copyright: Public domain

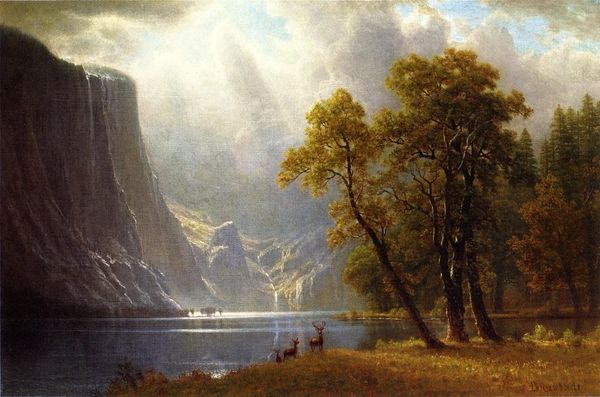

Curator: Bierstadt’s "Estes Park, Colorado," painted around 1869, presents a sweeping vista, a kind of monumental encounter with the American West. What strikes you first? Editor: The scale, definitely the sheer scale. But beyond that, it’s how manufactured the light feels, like theatrical lighting on this wilderness. You can almost smell the oil paint. Curator: Manufactured is a key word here. Bierstadt’s landscape, created with oil and tempera in plein-air, fits into the Hudson River School and its tradition of romanticizing nature to bolster national identity and manifest destiny. How do the materials speak to that? Editor: Well, oil paint allows for a hyper-realistic depiction—detail and layering give the impression of reality. The plein-air element, this supposed ‘direct from nature’ approach, attempts to mask the commercial and social incentives latent in depictions of unspoiled landscapes. Even the impasto adds texture that pulls the viewer in. Curator: Absolutely. Consider that, at the time, landscape painting also helped generate enthusiasm and, indeed, capital for railroad expansion and westward migration, frequently overlooking the indigenous presence in that area and other ethical concerns that remain unresolved even now. The deer here becomes a kind of shorthand for untouched wilderness, almost propagandistic. Editor: And consider how that representation translates materially into commodity. The image fuels fantasies, which translate into resources being extracted—gold, timber, land. All mediated by the smooth, inviting surface of the painting itself. And the photography, of course, allowed him to more precisely capture these details... Curator: The inclusion of photography alongside his painting makes you wonder about authenticity in general; about that "realism" we were talking about. It invites the question: is it just reproducing nature or reframing and molding the viewers' perspective, too? Editor: Right, it shows how landscape painting itself is labor – shaping perceptions, bolstering markets…It leaves you wondering about all that gets consumed. Curator: I suppose in a sense that’s part of Bierstadt's conflicted legacy; capturing breathtaking beauty, but often in the service of a much broader, more complicated agenda. Editor: Absolutely. You’ve reminded me how much these grand landscapes actively worked in the industrialization they seemed to be visually escaping from.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.