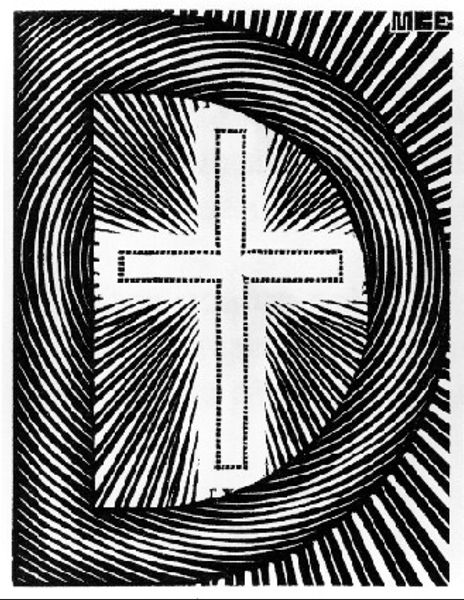

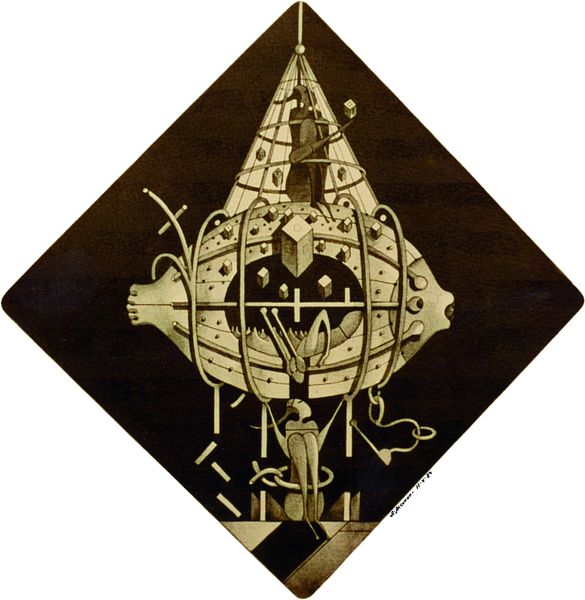

Copyright: M.C. Escher,Fair Use

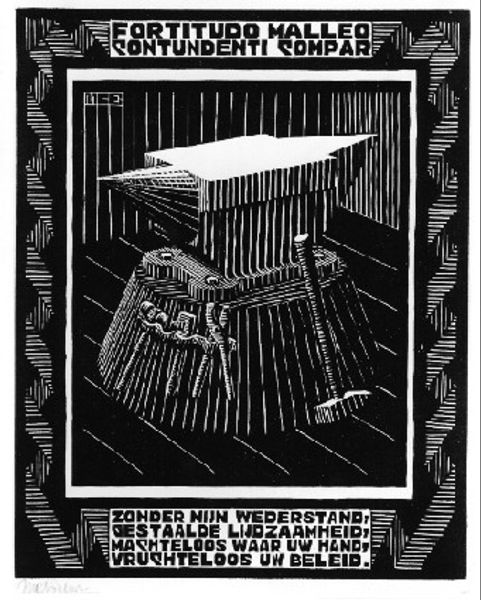

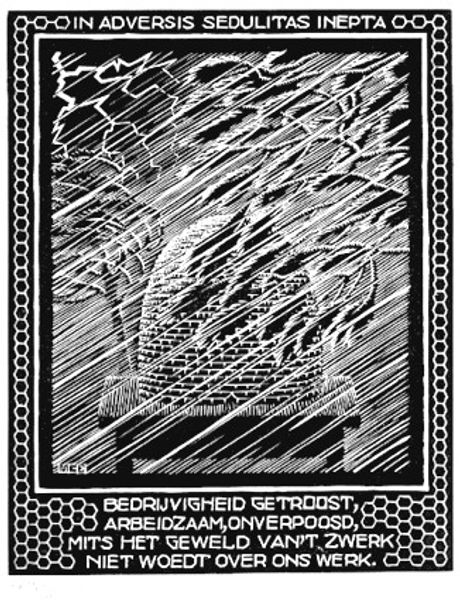

Curator: Standing before us is M.C. Escher’s woodcut, "Sundial (XXIV Emblemata: rejected plate)" from 1931. Editor: My first impression? Ominous elegance. Black and white, sharp lines… it's as if time itself is being dissected on a stark, unyielding surface. Curator: Precisely! Escher was obsessed with representing the passage of time, and here he presents a sundial—an ancient time-keeping device. Notice the inscription, "Patet Quaelibet Ultima Latae," Latin for “The final hour lies open to all”. The artist presents a play between the physical instrument and its symbolic meaning, urging one to contemplate temporality, especially human impermanence. What’s fascinating, and particularly in this woodcut, is the stark materiality itself. Look at the clear contrast in the printing. Editor: You know, I am intrigued by the mechanics here. Woodcuts involve carving away material to create a relief, meaning the areas printed in black are the raised, untouched parts of the wood block. What kind of labor was involved in carving something so precise and symbolic? Was there a division of labour? The frame including all 12 astrological symbols must have involved such precise handling of tools. It prompts thoughts about not only the physical process but also the potential economic structure, the workshops, the training…. Curator: Absolutely. Escher's prints often involve geometric patterns and illusions. The rays emanating from the sun, or rather the *absence* of wood that *creates* those rays, really amplifies the theme here: how the sun reveals or, in this instance, *obscures* time and shapes our perception. Did he reject it as not illusionary enough for his style at that stage? Editor: Interesting that this was rejected…perhaps he considered it a kind of artistic labour too close to clock-punching itself. Still, considering its creation through the labor-intensive woodcut process, what would otherwise serve a merely functional purpose takes on weight. I like how this plays into broader social concerns too; thinking about this piece in the context of the 1930s brings economic anxieties surrounding factory production to my mind! Curator: Yes, I'm glad we discussed these themes about the human condition. Now that our time is over, the experience urges one to seize time and embrace each moment, regardless of the passage of the literal seconds! Editor: For me, focusing on what's physical allowed me to look closer, prompting reflection upon labour’s weight in revealing these greater intangible mysteries, like time itself!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.