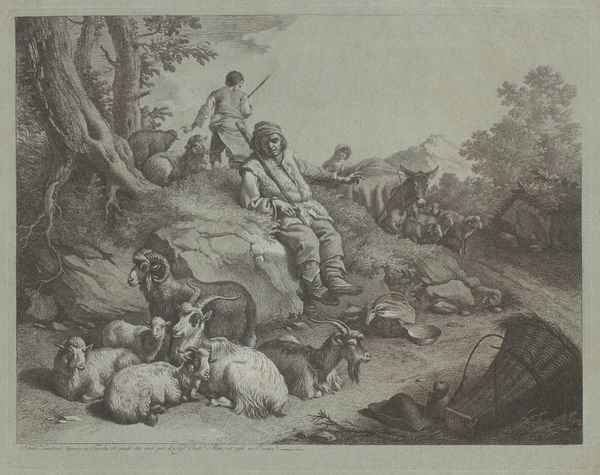

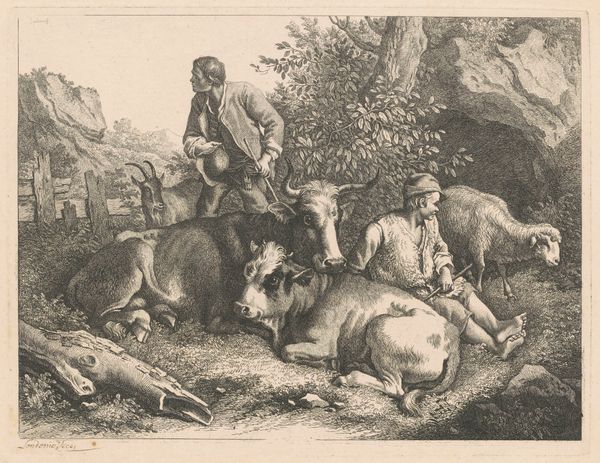

Seated Shepherd Boy and Woman Giving a Drink to a Child 1759 - 1782

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: plate: 26.6 × 34.6 cm (10 1/2 × 13 5/8 in.) sheet: 39.6 × 50 cm (15 9/16 × 19 11/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Let's consider this print, "Seated Shepherd Boy and Woman Giving a Drink to a Child," made sometime between 1759 and 1782 by Francesco Londonio. It strikes me as having an Arcadian tranquility. How does it resonate with you at first glance? Editor: I'm drawn to the stark tonal range Londonio achieves solely through engraving. Look at the layers of labour here, from the physical act of the artist incising the plate to the rural labor it depicts. The entire image speaks to cycles of creation and sustenance. Curator: Yes, it beautifully evokes a sense of simplicity and timelessness. I’m especially captivated by the figures: the shepherd, so serene with his flock in the background, and the tender interaction of the woman offering water. Water, of course, is such a prominent symbol of life, cleansing, rebirth… Editor: I’m intrigued by that "serenity." Doesn’t the idealisation of the peasantry sanitize the material conditions of rural labor? The shepherd's crook, the dog, these are all tools and materials involved in very specific work processes. The figures' garments, clearly worn, suggest the labour embedded within each woven thread. Curator: Perhaps. But consider that Londonio might be highlighting a moral purity found in rural life, an antidote to the excesses of urban society. The shared vessel for water suggests communal bonds, and echoes deeper ideas of shared beliefs or shared stories. Editor: True. The printmaking process itself echoes that, too. An original plate is laborious, a masterwork. And yet it exists to be reproduced, shared, consumed by many. What would the original audience, who likely could not afford the scenes represented here, made of it? It prompts contemplation about how art and its dissemination interacts with class. Curator: Ultimately, this work presents a pastoral fantasy where everyday acts gain significance. It’s a humble, humanistic portrayal—where universal experiences like offering water and tending sheep carry powerful messages. Editor: I agree. By exploring the social context surrounding its creation, we not only reveal much about the artwork's subject matter, but how social divisions also determined access to it. Curator: It certainly deepens our experience. Editor: Absolutely. A welcome exercise, indeed.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.