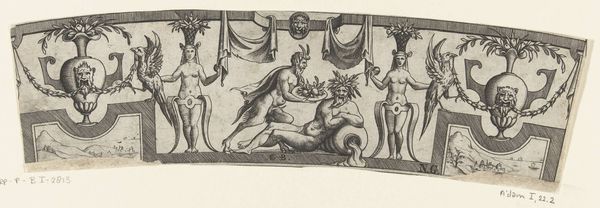

Licht gebogen fries, aan elk uiteinde een halve vaas op een sokkel 1516 - 1556

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

drawing, print, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

allegory

# print

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

ink

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 61 mm, width 150 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: The immediate impression I get is one of ritual, of something carefully and deliberately staged. What do you think? Editor: Well, the figures are arranged with an almost unsettling symmetry. And the texture, the way the ink catches, feels like uncovering something very old. Curator: Indeed. What we are looking at here is an engraving from the period between 1516 and 1556, titled “Licht gebogen fries, aan elk uiteinde een halve vaas op een sokkel.” Though anonymous, it's an intriguing example of Mannerist style currently held in the Rijksmuseum. The composition is striking: a curved frieze depicting allegorical figures and motifs. The symmetry and curvature speak to the ideals of beauty that reigned supreme in the art of the European Renaissance. Editor: Allegorical how? Because what strikes me is the way it reflects the tension between the classical and the fantastical. You have the semi-nude figures evoking classical sculptures, but then…a half-man, half-goat handing what appears to be water or maybe wine in a shallow bowl to a semi-nude bearded man. Curator: Right. That hybrid form immediately alerts us to symbolic content beyond literal representation. Satyrs are, of course, creatures of liminal spaces, intermediaries between the human and animal worlds. And water, in iconography, is commonly associated with purification and rebirth. The engraving employs a kind of visual language aimed to stimulate intellectual interpretation. The imagery may also serve as a memento mori or moral warning. The identity of the satyr here and the meaning behind the ritual of offering it performs before us remains open to various interpretations. Editor: This gets into something key for me. This anonymous artwork really highlights the tensions inherent in trying to impose grand narratives. Who are we to tell it what it's 'about'? Curator: An astute point. The fluid lines and exaggerated forms typical of Mannerism invite individual contemplation, not dogma. Editor: So while the Renaissance provides a specific context, its impact lies, perhaps, in this ambiguity, this almost deliberate open-endedness regarding symbolism and interpretation. The artwork, therefore, avoids being ossified by just one idea of its meaning. Curator: Agreed. This anonymous piece certainly provokes dialogue between historical understanding and our subjective encounter. Editor: Precisely, prompting a dynamic engagement beyond the constraints of definitive meaning.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.