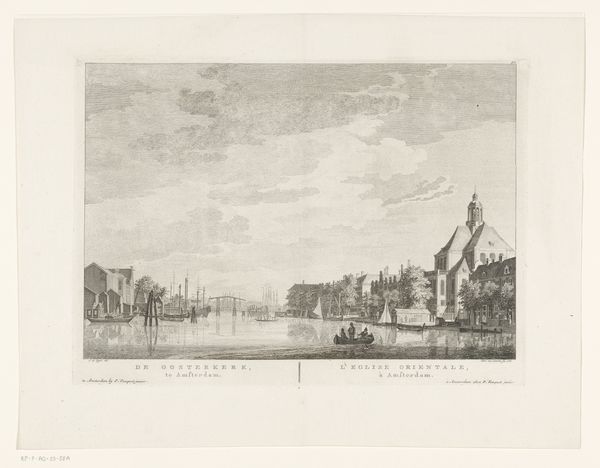

Gezicht op de Zuiderkerk, gezien vanaf de Raamgracht c. 1770 - 1783

0:00

0:00

hermanuspetrusschouten

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 268 mm, width 361 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Gazing at this engraving, “Gezicht op de Zuiderkerk, gezien vanaf de Raamgracht,” I'm immediately struck by the tranquil energy it evokes. Hermanus Petrus Schouten created this print around 1770 to 1783, now held at the Rijksmuseum. The whole scene shimmers with a kind of light. What is your take? Editor: What strikes me is the work it took. To get those lines so precise, the biting of the plate, the evenness of the ink… it’s a testament to skilled labor, all to create a reproducible image of Amsterdam’s Zuiderkerk. Consider the cultural and economic capital tied to this printing. Curator: Absolutely. And yet, for me, it goes beyond mere reproduction. Notice how the baroque style lends an almost dreamlike quality to a rather mundane urban landscape? It feels almost…nostalgic, maybe? The light, those carefully etched details…it’s less a factual representation and more a feeling. Editor: Interesting point. What materials would Schouten have had access to? The paper, the inks—what were their sources? It shifts how we understand his role, he is not this solitary artist with a unique vision but part of an entire economy, reliant on specialized knowledge and the labor of others. The end result here is that every family could have this memento of the Netherlands’ thriving. Curator: I think you are right, but let's not disregard the subjective skill, capturing the quiet moments amidst that "thriving," as you said. Take the figures in the boats or walking along the canal… there’s an intimate story within those broader socio-economic structures. Editor: It's almost like these artisans were contracted out to develop and disseminate images which reinforce the status quo and Dutch trade and societal structures as divine and virtuous; the light which emanates is not happenstance at all, and those small subjects fulfill those roles of daily life. Curator: Perhaps. Ultimately, the beauty of this lies, not only in the artistry and history bound to its materials but in the myriad feelings it stirs—melancholy, peace, even a kind of quiet joy in simply observing a world now long past. Editor: I find myself admiring the way it makes visible the otherwise invisible—the sheer physical effort of its making. It’s an invitation to look beyond the pretty image, to consider the network of things and people necessary for art—or, for a humble city view—to exist.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.