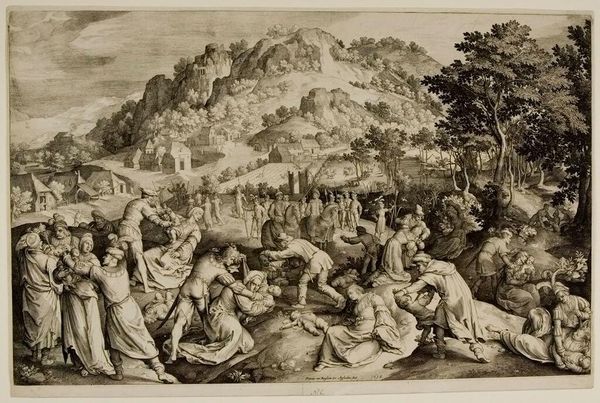

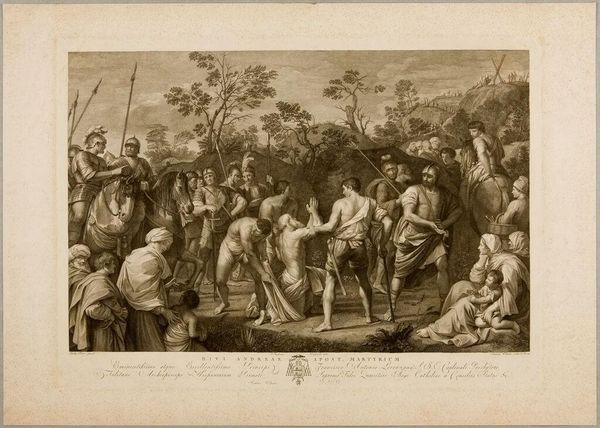

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

ink drawing

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: width 687 mm, height 433 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us is a stark engraving titled "Kindermoord van Bethlehem," or "Massacre of the Innocents," made sometime between 1612 and 1665, and we attribute it to Nicolaes de Bruyn. It depicts a rather brutal biblical scene. Editor: My immediate thought is...it's chaotic. There’s a frenzy of activity packed into this landscape, a swirling vortex of human figures dominated by muted tones and this unsettling sense of violence erupting in a pastoral setting. Like a nightmare in the Garden of Eden. Curator: Precisely. De Bruyn translates the biblical narrative into a vividly disturbing spectacle. Note how the spatial arrangement and composition intensifies the sense of brutality. It isn't just the event itself that's presented, but a statement on social disorder. The landscape itself seems to reflect the emotional upheaval. Editor: And that landscape, with the placid, rolling hills in the background… almost mocking the horror playing out. There’s something so perverse about juxtaposing the grotesque with the beautiful. It’s like nature is indifferent to human suffering. Is this commentary, do you think, on divine indifference? Curator: It is difficult to say whether indifference is presented or, perhaps, a lack of intervention. Baroque art often explores dramatic, even theatrical scenes, but also morality. The intent here may be to provoke introspection. After all, art of this era played a pivotal role in reinforcing the influence and moral authority of the Church. Editor: Introspection…or just pure shock value? There's almost a relish in detailing the gruesome, I see desperate mothers, enraged soldiers…each tiny scratch of the engraving knife adds to the escalating feeling. It’s manipulative, and effectively so. I wonder about the psychology of the viewer then versus now. Do we react the same way? Curator: The power of the image lies in its ability to confront audiences with difficult realities and ethical dilemmas. By experiencing this scene, early modern viewers were implicitly invited to examine their beliefs and actions in a context both religious and political. Today, the work retains that capacity to provoke important, often uneasy questions. Editor: Absolutely. It still churns something up inside, that tension, the dance of life and death frozen in ink. It reminds me, brutally, how art can hold a mirror to the darkest corners of human nature. Curator: Indeed. De Bruyn's "Massacre of the Innocents" serves as both historical record and a testament to the enduring power of art to stir uncomfortable truths.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.