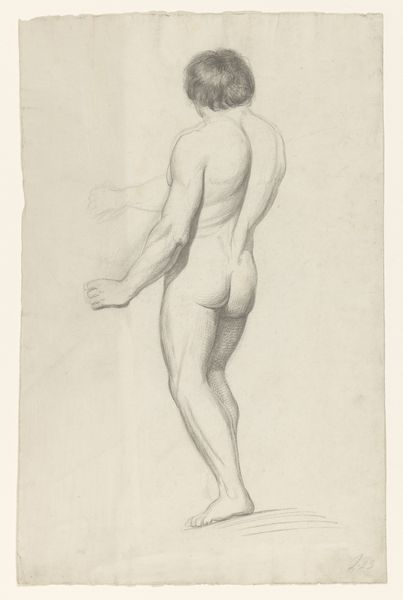

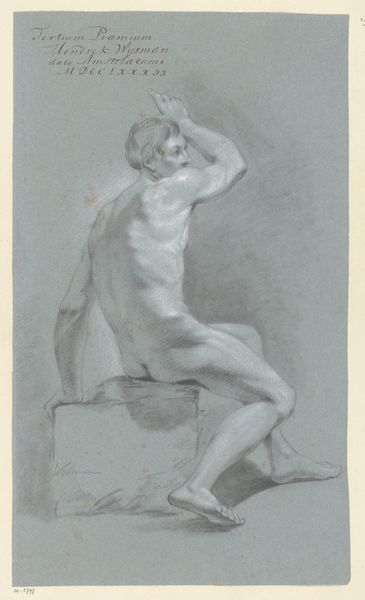

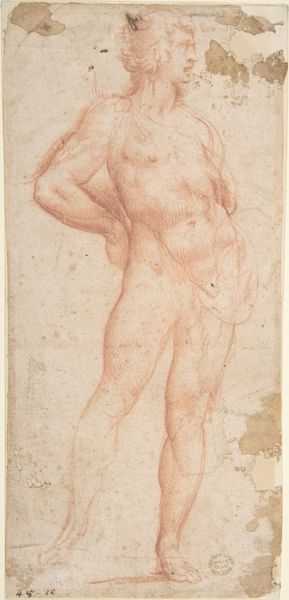

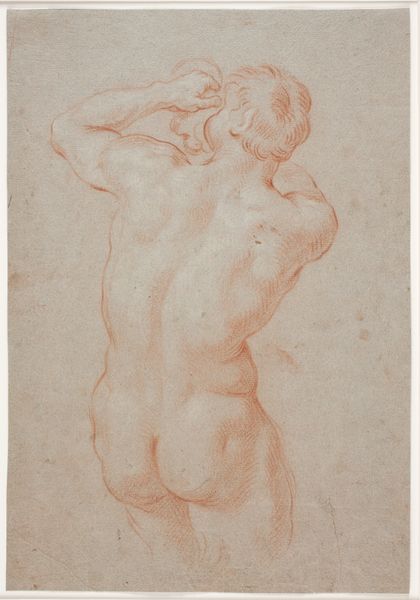

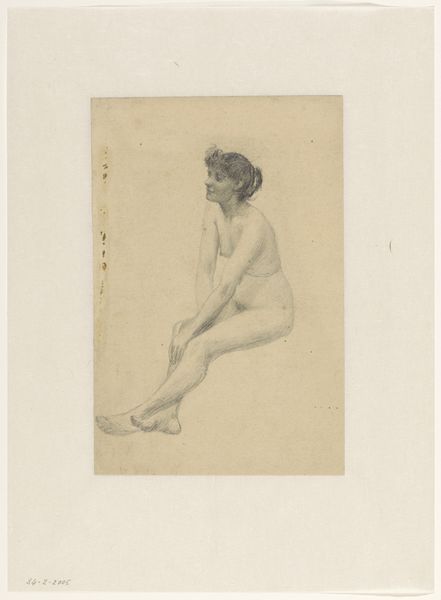

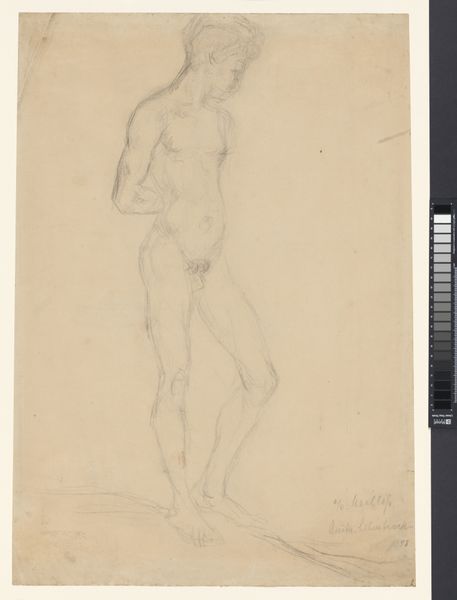

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

form

#

pencil

#

line

#

academic-art

#

nude

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 272 mm, width 143 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

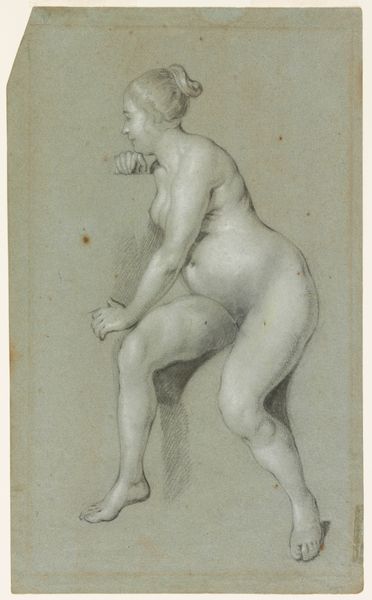

Curator: Let's talk about Jan Brandes's "Seated Female Nude," believed to have been created sometime between 1787 and 1808. It's a pencil drawing, very classical in its approach. Editor: My immediate response is that of contemplation and perhaps even exhaustion. The figure seems withdrawn, the gaze lowered. It makes me question the very act of observation. Who is allowed to look, and what is their power dynamic with the subject? Curator: Well, nude studies such as this were, of course, fundamental to artistic training in that period. Brandes, given his position in Dutch society and artistic circles, likely created this as a formal exercise, studying form and anatomy, conforming to prevailing academic standards of his era. We also know he traveled extensively, documenting colonial encounters and interactions, so I'd wonder if we can read gendered, colonial dynamics here as well. Editor: That's fascinating! Because, to me, there's a vulnerability here that transcends the purely academic. I mean, yes, it's clearly an exercise in depicting the human form, but I'm drawn to the lines around the figure’s neck and shoulder, a very nuanced and realistic rendering. The absence of idealization, or rather the deliberate non-idealization, feels very much like a political statement, even unintentionally. The history of the male gaze is intrinsically intertwined with art history. The rendering itself does have qualities related to realism in my view, more than a sterile "study of the form." Curator: I see your point. But think about where these works were likely viewed – within the closed doors of an academy, perhaps, not meant for public consumption or political interpretation as such. Though I am curious, Brandes produced a substantial number of drawings depicting human subjects. Are those subjects all from similar origins or positions within society? How might that have colored the approach toward the study of form and anatomy? Editor: That kind of critical background adds layers, especially in the light of feminist perspectives on art and representation. How are we looking at bodies that might historically have been considered "other?" To critically approach an image like this from 1787, we're in a sense using our viewing position today to reflect critically on Brandes' own context and how it's shaped even seemingly apolitical choices in artmaking. Curator: Precisely. Situating works in their full political and social context helps to reframe traditional readings. It shows how institutions are as vital when understanding art from that era. Editor: A vital dialogue indeed. This offers an opportunity to analyze representation of race, class and gender back then and still now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.