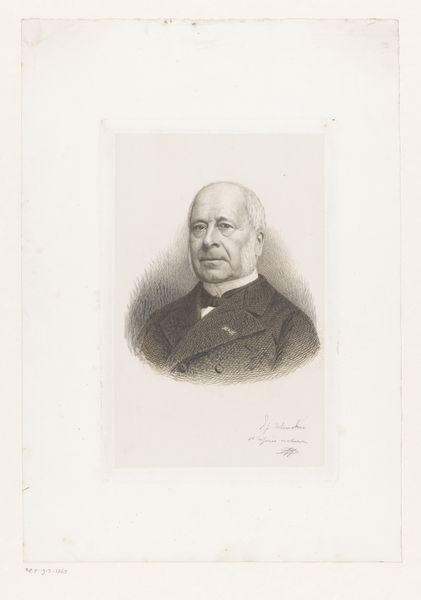

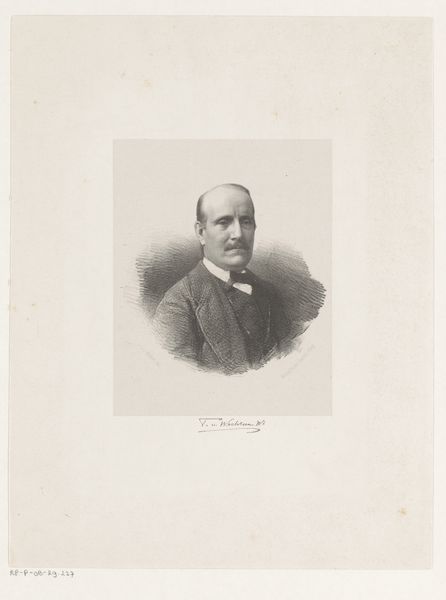

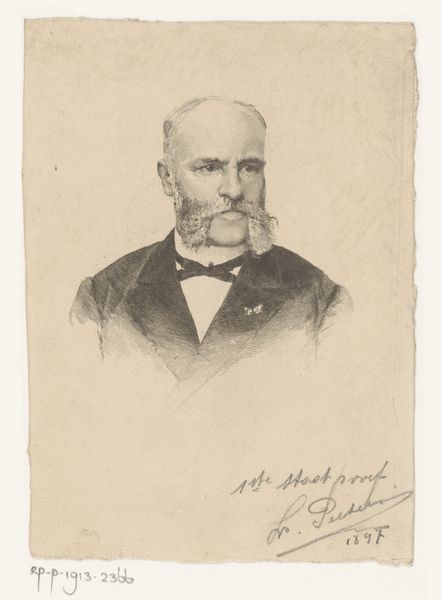

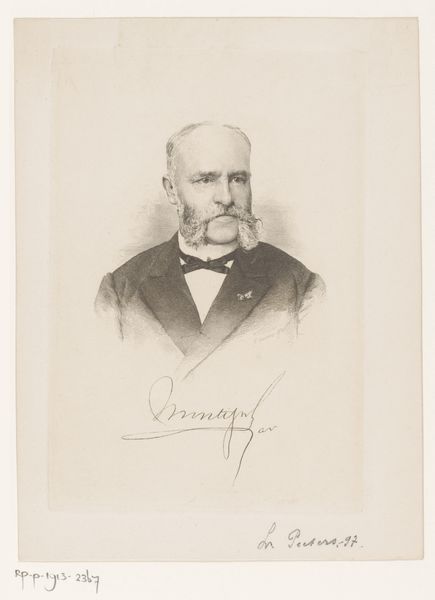

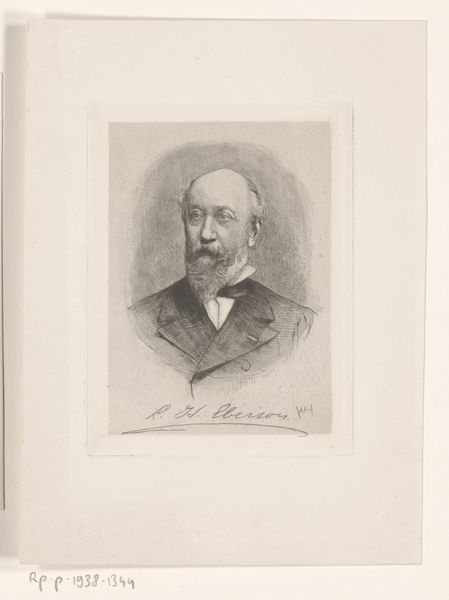

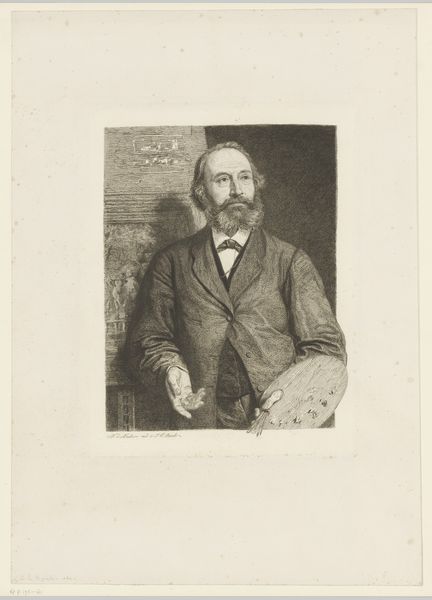

drawing, charcoal

#

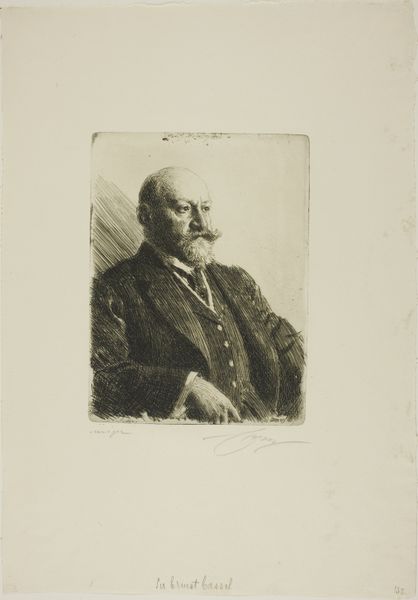

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

charcoal drawing

#

pencil drawing

#

portrait drawing

#

pencil work

#

charcoal

#

realism

Dimensions: height 418 mm, width 292 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have August Allebé’s "Portret van een zittende heer met sigaar, op 64-jarige leeftijd," created in 1889. It's a drawing done with charcoal and pencil, and it strikes me as very formal and controlled. I'm curious, what do you see when you look at this piece? Curator: I see a deliberate construction of bourgeois identity. Look at the precision of the lines, the rendering of the fabrics, the inclusion of the cigar – it's all about portraying a man of means. What kind of labor went into creating and circulating an image like this at that time, and who was it intended for? Consider the raw materials—paper, charcoal, pencils—transformed through skilled labor into a commodity representing social status. Editor: So you’re thinking about the economic implications? The cost of the materials and the artist's time? Curator: Precisely. The availability of materials like quality paper and pigments, the specialized skills of the artist—these were not universally accessible. The drawing signifies access and privilege, made tangible through the very materials and techniques employed. It challenges us to think about art not just as aesthetic expression, but as a product embedded in systems of labor and exchange. How does this relate to traditional academic portraiture, and how does Allebé depart from those established conventions? Editor: It feels more immediate, less idealized maybe? It's a drawing, not a grand oil painting. Curator: Exactly. That shift towards a seemingly more 'accessible' medium perhaps reflects a changing perception and consumption of art. However, that "accessibility" might be deceptive. Consider the cultural capital embedded even in this drawing, compared to folk art of the same period. It still represents a distinct level of privilege. Editor: I never considered the layers of economic and social context just in the materials. Curator: Thinking about art this way allows us to dismantle the romantic notion of the solitary genius, revealing the networks of production and consumption that shape even the simplest sketch. It allows us to place the portrait within broader debates about class and artistic value in 19th-century Netherlands.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.