![[Ditch and Chevaux-de-frise, Fort Sedgwick, in Front of Petersburg, Virginia] by Timothy O'Sullivan](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzL2EwNGE5MTg1LTIxYWItNDM0Yy1iYzkyLWEwMDY4MTlkOTQwOC9hMDRhOTE4NS0yMWFiLTQzNGMtYmM5Mi1hMDA2ODE5ZDk0MDhfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

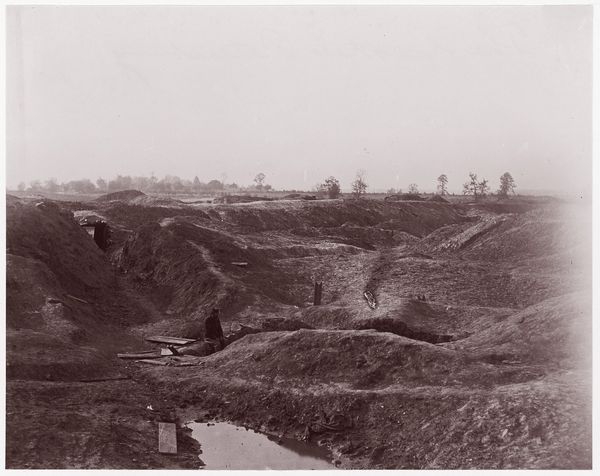

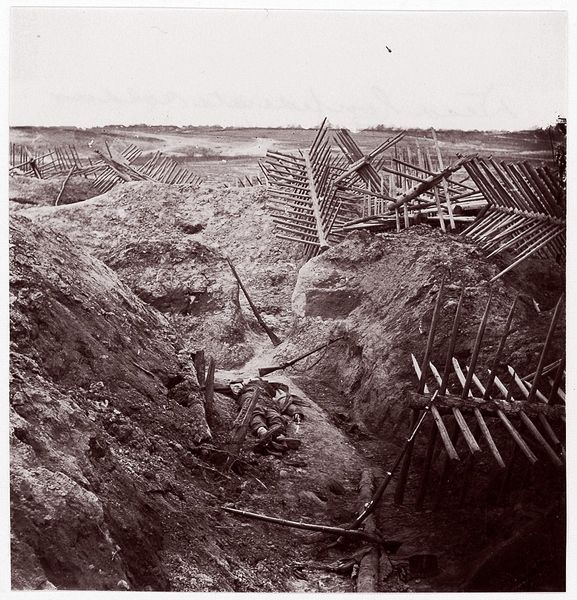

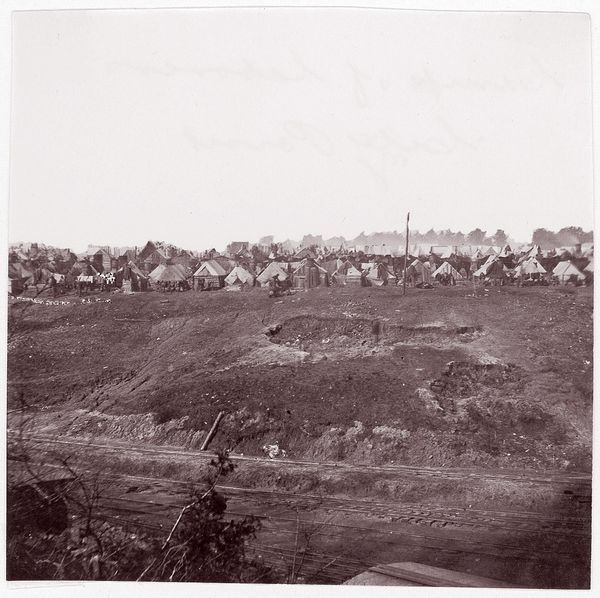

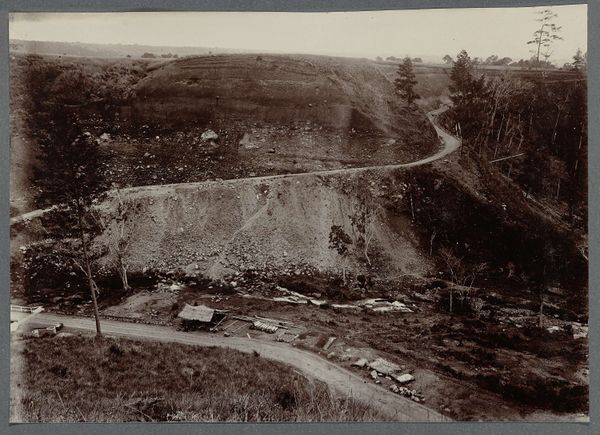

[Ditch and Chevaux-de-frise, Fort Sedgwick, in Front of Petersburg, Virginia] 1865

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

war

#

landscape

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

monochrome photography

#

history-painting

#

monochrome

Dimensions: 8.7 x 9.4 cm (3 7/16 x 3 11/16 in. )

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: So, this is Timothy O'Sullivan’s photograph, "[Ditch and Chevaux-de-frise, Fort Sedgwick, in Front of Petersburg, Virginia]," taken in 1865. It's a gelatin silver print showing a landscape of war. There's a stark, unsettling stillness about it. How do you interpret this work in the context of its time? Curator: I see it as a potent commentary on the brutal realities of the American Civil War, particularly concerning labor, race, and the body. The stark landscape, devoid of idealized heroism, speaks volumes. O’Sullivan’s photograph avoids glorifying war, instead showing the dehumanizing effects of the conflict through this desolate, almost lunar, terrain. Consider the forced labor that went into creating these fortifications. Who do you think was forced to build them? Editor: I hadn’t really thought about that. You're right, it wasn't just soldiers involved in war. It would have been enslaved African Americans, or very poorly paid immigrant labor too. Curator: Exactly. The photograph, then, becomes a stark document of not just physical landscape, but also the socio-political landscape marked by inequality and exploitation. How might contemporary viewers engage with this image in light of current conversations around monuments and historical representation? Editor: It definitely complicates the narrative we tell ourselves about history. It pushes beyond the sort of simplified patriotism and towards a more uncomfortable truth about the human cost of war and inequality, even in landscape. Curator: Precisely. And isn’t it interesting that he chooses a seemingly neutral landscape, one that’s been completely transformed by human activity? What is more landscape than ditches, forts and defenses? O’Sullivan prompts us to consider whose bodies built this landscape, and to whose benefit. Editor: I hadn't considered all those layers of interpretation before. I'm starting to appreciate the power of documentary photography in shaping and challenging historical narratives. Curator: And I think this reveals that we all, especially now, have to bring intersectional thought to images in any museum to learn and improve.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.