photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

water colours

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 81 mm, width 50 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

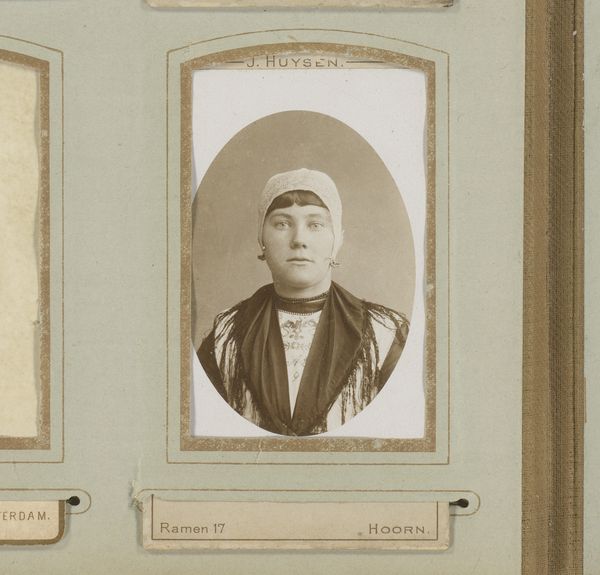

Curator: This gelatin silver print, dated between 1883 and 1910, is attributed to Johannes Laurens Theodorus Huijsen and is titled "Portret van een vrouw," or Portrait of a Woman. It's currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It strikes me immediately as a rather sober and straightforward depiction. The sitter gazes directly out, her expression somewhat…unyielding? It's a very composed portrait. Curator: Indeed. In the late 19th century, photographic portraiture gained prominence not just as an artistic form but as a vital element in constructing social identity. Consider that portraits like these were becoming accessible to a wider segment of the population, not solely the aristocratic elite. It documents the burgeoning middle class. Editor: Right, the advent of photography offered new ways of memorializing oneself. Her gaze certainly communicates something of that burgeoning confidence. Her jewelry, for example. Are those mourning symbols in her brooch and necklace? Curator: It’s quite possible. Accessories frequently encoded messages about status, allegiances, or life events. This type of jewelry may reflect a personal sentiment in a more modest and discreet way, while also maintaining conventional propriety. Editor: So the visual language provides both information and context. It's intriguing to ponder what messages she intended to send—and what meaning these accessories might hold to later viewers. Curator: Exactly, and beyond the immediately identifiable symbolism, there are layers of cultural nuance. It serves as a microcosm of how ordinary people wished to be remembered. A record for her family and descendents to cherish and identify with. Editor: A tangible connection to the past. Well, this glimpse into the world and identity of a woman from over a century ago leaves me wondering about her individual story beyond this portrait. Curator: Agreed. These pieces are potent historical evidence; snapshots that are representative of how people chose to portray themselves in their unique contexts, and to influence how history might eventually view them.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.