drawing, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

paper

#

ink

Copyright: Public Domain

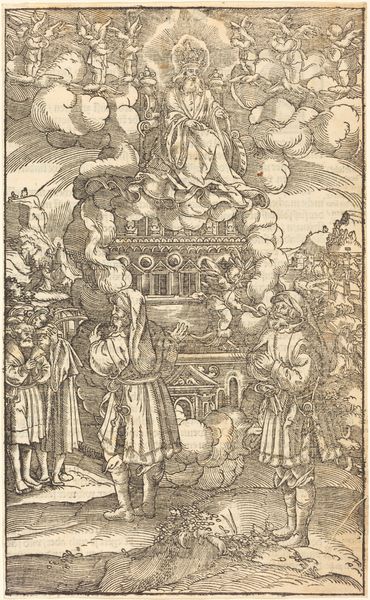

Curator: Before us, we have Hans Jakob Dünz’s 1600 ink and paper drawing, "The Raising of Tabitha by Saint Peter," currently residing at the Städel Museum. Editor: Oh wow, okay. So immediately, the muted palette and unfinished quality… it gives the scene an almost dreamlike vulnerability, like we’re peeking into a half-remembered story. There's so much detail yet so much open space, I keep circling back for details and almost catch movement within the sketch. Curator: Absolutely. And situating this work within its time, consider the socio-political currents. Dünz, working at the dawn of the 17th century, inherited a Reformation-tinged environment which impacted iconographies, leading artists to find clever modes to revisit the power dynamics, faith, gender, and miracle themes. Editor: It is fascinating how, even with that contextual pressure, there’s a softness. Tabitha's reclining pose and Peter's slightly hesitant gesture, even in the sketch, invite us to feel their fragility and perhaps a shared anxiety of such moments of divine intervention? It’s really compelling as something less about godly intervention, more about fragile humanness at its most desperate and full of longing. Curator: Precisely. By focusing on the bodily vulnerability—the averted gaze, the slackness of the limbs, even the almost casual arrangement of bowls on the small table nearby, Dünz creates a powerful tension between miracle and mundane. Feminist art historical interpretations can really expose this relationship, examining how the story has often erased the feminine. Editor: See, the sketch medium kind of adds to that point for me. I see potential erased outlines and it reminds us the image is constructed…constructed ideas, you know? The female figures, even around such a dramatic moment of restoration to life, stand somewhat passively observing, a subtle critique of the active/passive binary imposed in religious narratives perhaps? The more defined cupid in contrast brings some kind of… dark ironic note. Curator: Yes. It raises the crucial point, who is the audience here? Was this perhaps commissioned work pointing toward specific theological interpretations, even propaganda, reflecting an environment attempting to navigate deep gender roles within spiritual narratives. Editor: I really hadn’t even thought of it that way—I had seen the image as dreamlike and sensitive—but its polemical capabilities do change everything, when you place it within its historical context. What appeared emotionally honest I suddenly view with renewed perspective as politically complex and perhaps even transgressive for its time. Curator: Context truly is everything; bringing intersectional lenses to art is often more complex and fruitful, while offering greater empathy to artwork in a world not our own. Thank you for sharing your personal view.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.