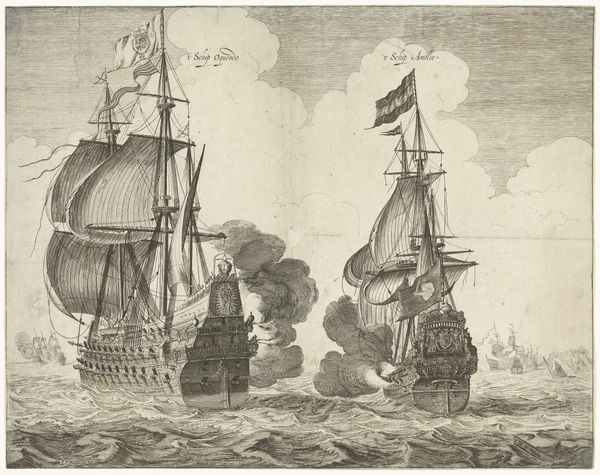

A Naval Encounter between Dutch and Spanish Warships c. 1618 - 1620

0:00

0:00

painting, oil-paint

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

landscape

#

oil painting

#

history-painting

Dimensions: overall (sight size): 47.63 x 141.61 cm (18 3/4 x 55 3/4 in.) framed: 66.68 x 159.39 cm (26 1/4 x 62 3/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Editor: Ah yes, “A Naval Encounter between Dutch and Spanish Warships” from circa 1618-1620 by Cornelis Verbeeck, done in oil paint. I'm struck by the details rendered considering the instability of the sea and weather. What catches your eye about it? Curator: What interests me here is less the romantic depiction of naval power and more the actual labor involved. Imagine the manpower needed, not just for sailing and fighting, but also for sourcing the materials: the lumber for the ships, the flax for the sails, the iron for the cannons. Consider too, the economic and social contexts that propelled that labour, and who actually benefited. Editor: So, you're looking beyond the battle itself to consider the resources required? I suppose that's easily overlooked, just considering it history, which feels static, somehow. Curator: Precisely. We should be thinking of global trade routes at this time. These warships protected or threatened such networks, all of which were underpinned by systems of production. And how the materials themselves might inform the artwork. Think about the artist's labor, from the pigment sources to the weaving of the canvas. This is an “oil painting”. How does oil paint itself relate to contemporaneous economics? Where do we find its source? Editor: That’s really interesting to consider oil paint as an active ingredient within trade rather than as a static material. Were the materials and tools used by Verbeeck considered important at the time, or was that concern further down the road? Curator: Initially, the focus would’ve been on the artistry, the composition. Over time, however, and especially with new methodologies, it is useful to view materials as agents within these systems, reflecting the labour, technologies, and economics of the period. The social history behind any painting changes what it stands for. Editor: I hadn't considered the broader economic picture embedded within the piece. I'll definitely be thinking about the implications of materials when I look at other works from now on. Thanks for offering that. Curator: And I find myself wanting to consider not only what went into the piece, but what comes out: how a piece depicting conquest still plays its role in systems of labour and trade now, in its acquisition, preservation, display and analysis. Always a fascinating dialectic.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.