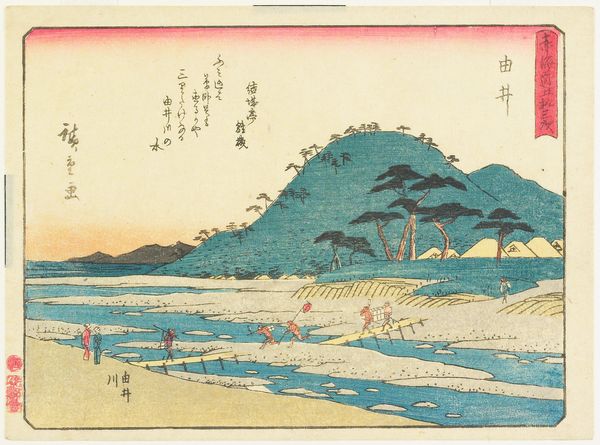

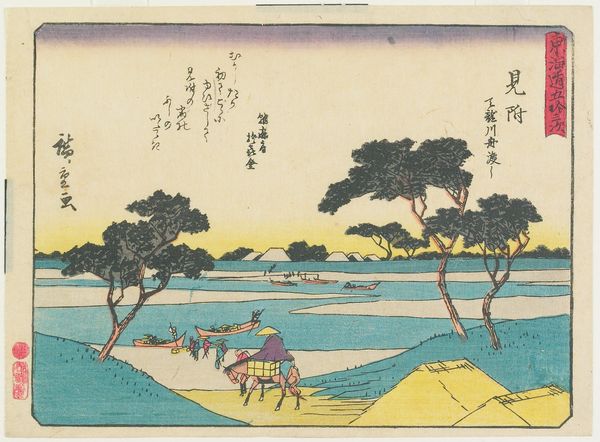

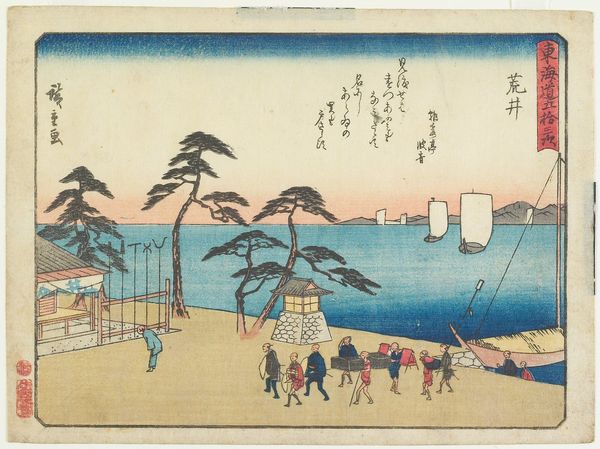

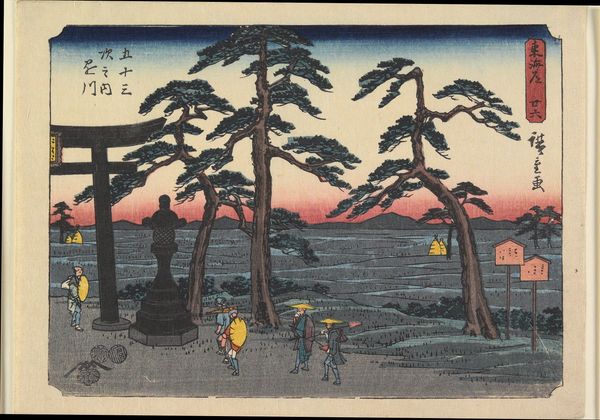

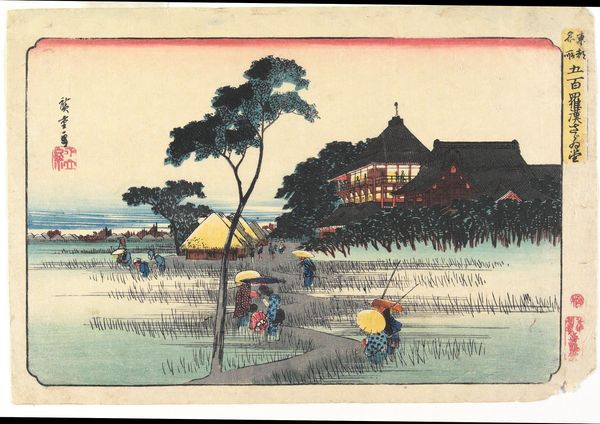

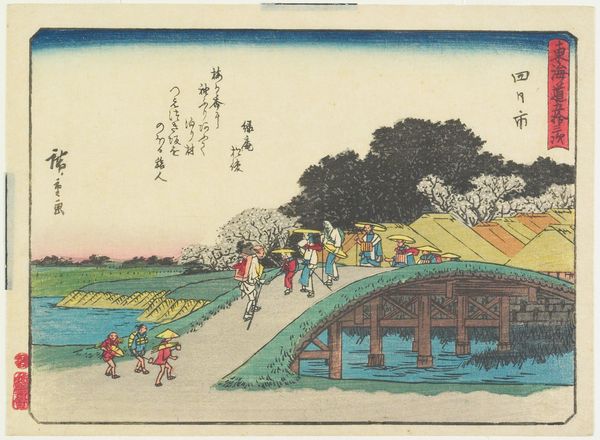

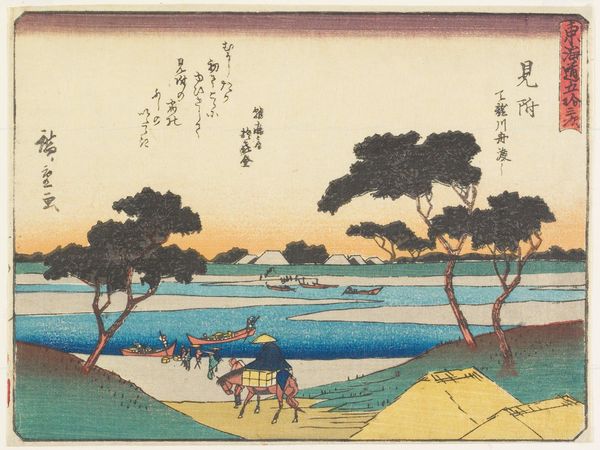

View of Listening to Crickets at DōkanHill c. 1839 - 1842

0:00

0:00

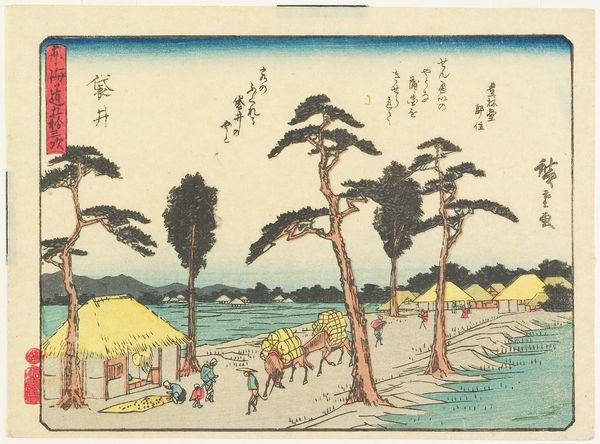

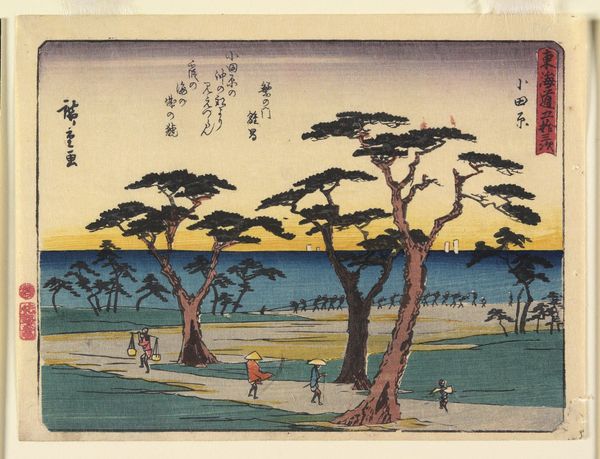

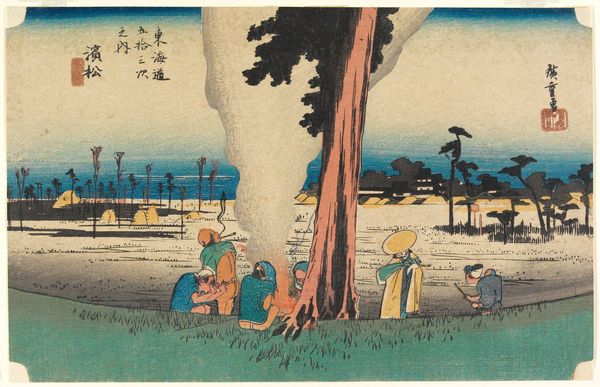

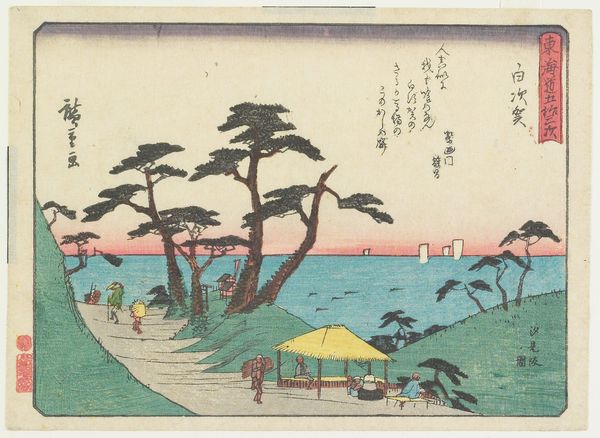

print, paper, ink, woodblock-print

# print

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

ukiyo-e

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

woodblock-print

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: 8 11/16 × 13 3/8 in. (22.1 × 34 cm) (image, horizontal ōban)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: So, this is "View of Listening to Crickets at DōkanHill," a woodblock print by Utagawa Hiroshige, from around 1839-1842. There's a real sense of everyday life here; people picnicking, others strolling… How do you interpret the way Hiroshige portrays leisure in this context? Curator: That’s a great starting point. Hiroshige's depictions of leisure offer fascinating insights into the Edo period. It wasn't simply about relaxation; it was carefully structured, performed, even politicized. These images, circulated widely, presented a controlled vision of Edo society, shaping perceptions of culture, stability, and pleasure under the Tokugawa shogunate. What social classes do you think are represented? Editor: Hmm, judging by the clothing, likely merchants or perhaps prosperous artisans, right? Not the samurai class. Curator: Precisely. Woodblock prints like this catered to, and shaped the tastes of, the burgeoning merchant class. They craved depictions of themselves enjoying the fruits of a peaceful, commercial society. But also consider, who gets to define "leisure," and whose leisure is visibly celebrated versus obscured? How does this influence our own perspective on historical representations today? Editor: That’s really interesting. It’s almost like these prints were early forms of social media, constructing an image for public consumption! It also makes you think about who *isn't* represented – the rural populations, the lower classes. Curator: Exactly. The "ukiyo-e," or "floating world" prints weren't mirrors, they were filters, selectively reflecting particular values and power structures. Reflecting upon this informs contemporary discussions around whose stories are told and preserved in art, and what implications this has for how societies are remembered and understood. Editor: I see. I’ve always admired these prints for their beauty, but thinking about the politics behind them makes them so much more complex. Curator: It certainly does. The intersection of aesthetics, social history, and power dynamics offers invaluable insights into both art and culture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.