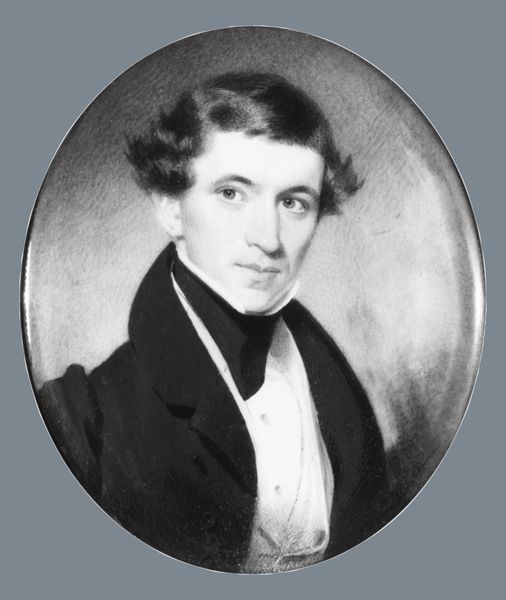

drawing, paper, graphite

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

paper

#

romanticism

#

black and white

#

men

#

graphite

#

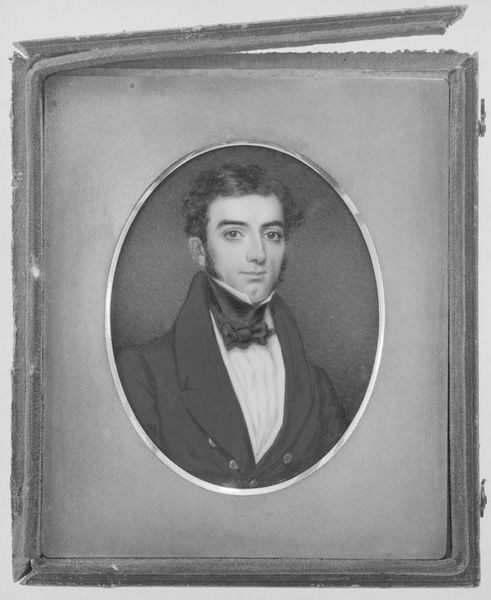

miniature

Dimensions: 2 13/16 x 2 3/16 in. (7.1 x 5.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

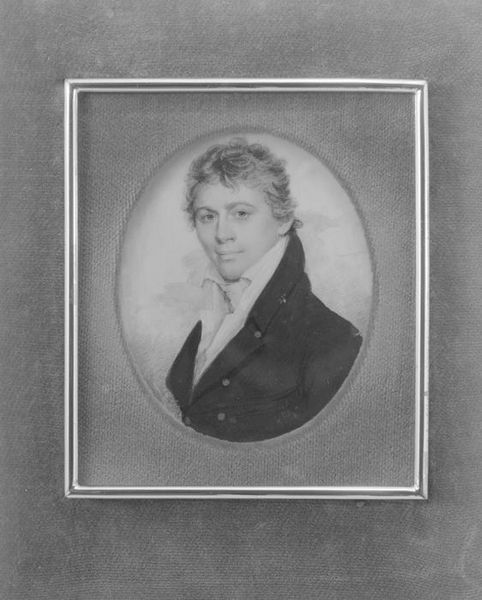

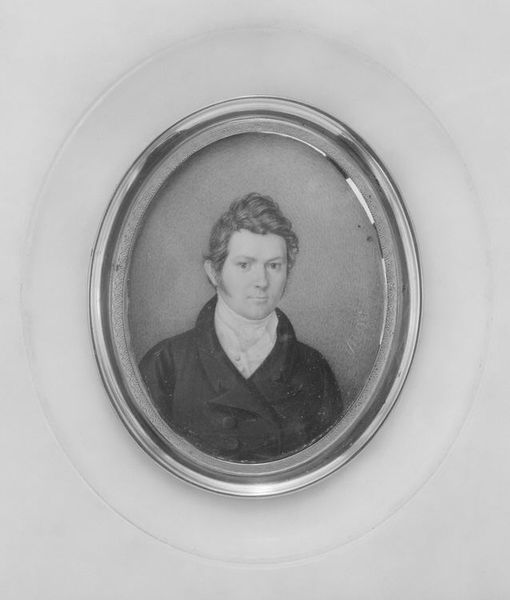

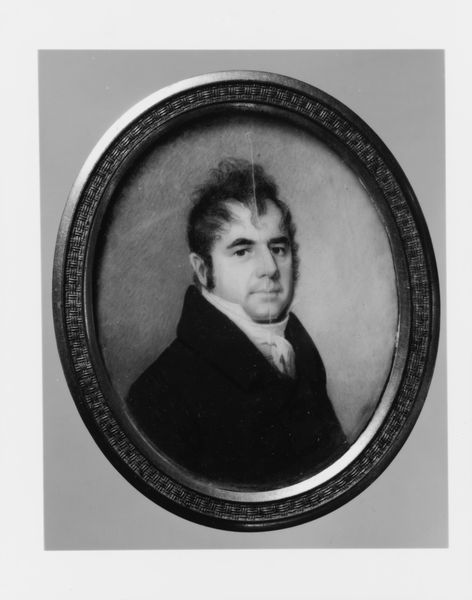

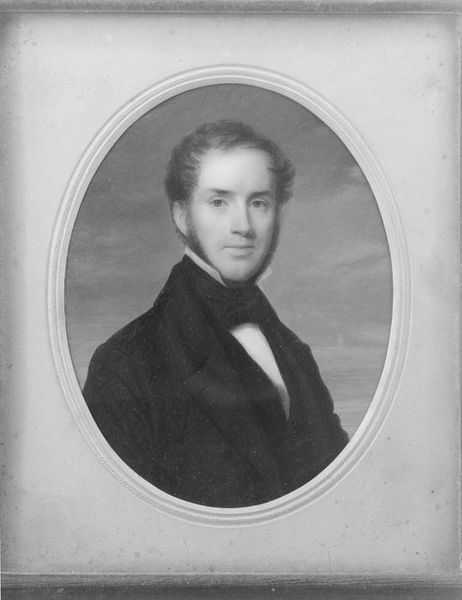

Curator: Here we have Benjamin Trott's portrait of Charles Wagner, a graphite drawing on paper, created sometime between 1810 and 1820. Editor: It’s striking, this tiny window into the past. The stark contrast emphasizes the sitter's youth, but there's also something undeniably melancholic in his expression. Curator: Indeed. The size speaks volumes; these miniatures were often intimate objects, meant to be held, cherished, and circulated among a close circle. We see Romanticism influencing Neoclassical portraiture, evident in the emotional intensity contrasting with the clean lines and idealized form. Editor: And let's consider the materiality of the piece. Graphite, seemingly simple, allows for such nuanced shading. It makes me wonder about the artist’s studio, his access to materials, and how those costs played into who was memorialized this way. Curator: Precisely. This was a period when portraiture was shifting from oil paintings commissioned by the elite to more accessible, though still precious, formats like drawings and watercolors. It democratized representation somewhat. What stories might this drawing have silently witnessed over the decades, passed between family members, kept as a token of love or remembrance? Editor: It forces us to confront the power dynamics inherent in portraiture. Who gets represented, and by whom? Wagner, undoubtedly a person of some status, actively participated in his own visual narrative through patronage, becoming both subject and consumer. It also begs the question: How were these kinds of artistic commodities used? What kind of political, sentimental, and cultural capital was accrued by producing, consuming, and circulating portraits like this? Curator: These miniatures functioned as status symbols, sentimental keepsakes, and tools for solidifying social bonds. Thinking about this work displayed here, we need to understand how museums continue shaping art’s reception. Editor: It prompts such fascinating questions about the relationship between the artist, the sitter, and the viewer, across time. Curator: Absolutely. Seeing the work up close makes us think more deeply about the hands that made it, and the complex networks within which this image traveled.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.