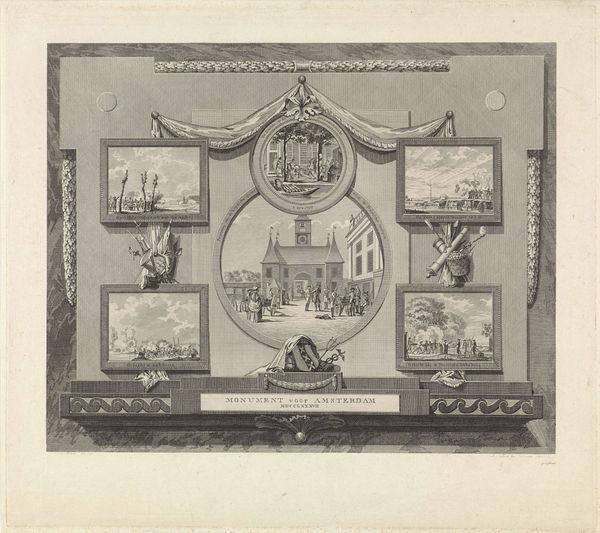

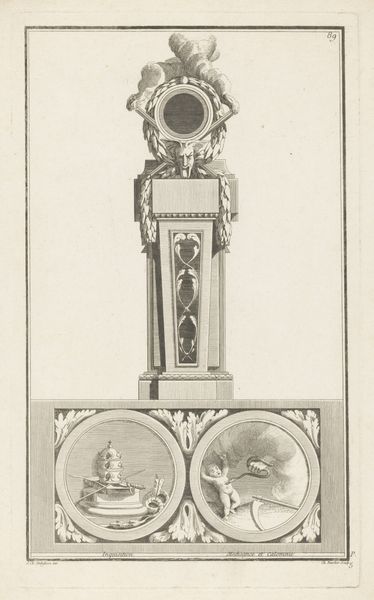

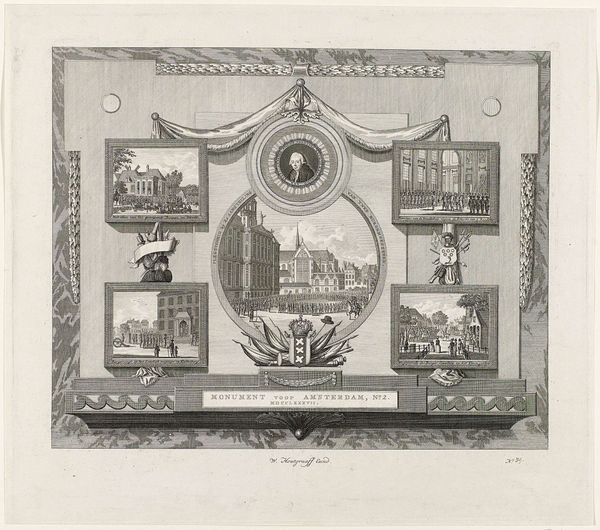

Zes medailles met voorstellingen uit de Franse geschiedenis 1702 - 1767

0:00

0:00

jacobfolkema

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

caricature

#

history-painting

#

engraving

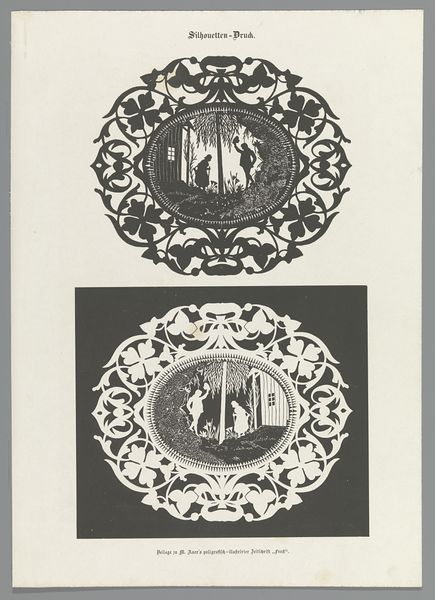

Dimensions: height 223 mm, width 161 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

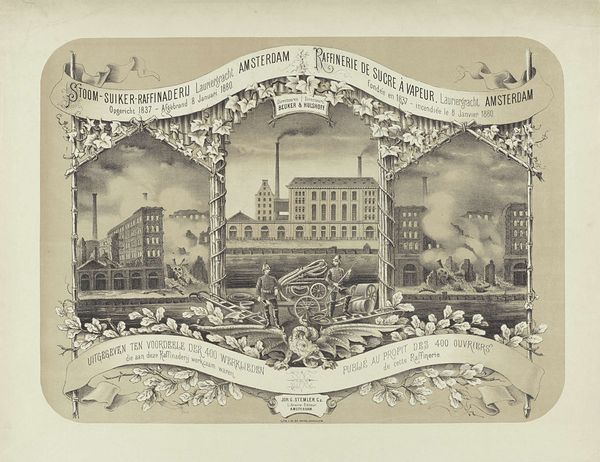

Curator: Looking at this engraving, "Zes medailles met voorstellingen uit de Franse geschiedenis"—"Six Medals with Scenes from French History"—crafted between 1702 and 1767, primarily with engravings, what jumps out at you? Editor: Oh, my goodness, it's like peering into a tiny, bustling world! It feels theatrical, with all the distinct vignettes laid out almost like a storyboard for a grand historical drama. Curator: That’s a great observation. The artist, Jacob Folkema, truly presents these historical moments with an almost narrative intensity. For me, I keep thinking about the engraver’s hand—the precision, the sheer labor of detailing these minuscule scenes. Imagine the workshop, the tools, the almost monastic focus required. Editor: Absolutely, I see a fascinating interplay between craft and what you could even call propaganda. These medallions weren’t just decorative; they were meant to shape perceptions, perhaps solidify certain political narratives through mass production of printed imagery. I wonder about their role in disseminating royal or aristocratic ideas… Curator: Precisely! Engravings like these were incredibly effective for circulating narratives. It's almost like the social media of the time—distributing ideas and stories visually, in a reproducible format. Editor: And that medium dictates so much of the message. An engraving isn't a painting, right? It isn’t a unique, bespoke object made of oils and pigment but a multiplication of image through labor, etched line by etched line. The starkness of black and white lends a certain gravity, maybe even a sense of “officialdom” to these scenes, regardless of their factual basis. Curator: And the material aspect—paper, ink, the press—they're not just neutral conveyors. They subtly inform how people understand history. Consider how that changes who can access the representation. This medium lowers the threshold for viewership dramatically, disseminating information into the culture more democratically…sort of. Editor: Yes, there’s something to be said about the distribution mechanism itself. Think about how the meaning shifts when a historical scene goes from, say, a painted portrait accessible to an elite few, to an engraving that can be disseminated to the masses—each impression a physical record of production and ideological intention. Curator: So much about this points to that very act of production, that it becomes hard not to think about where the art begins. Editor: Definitely, and reflecting on this piece, it's a good reminder that artworks don’t just reflect history; they’re actively *making* it in tangible, material ways.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.