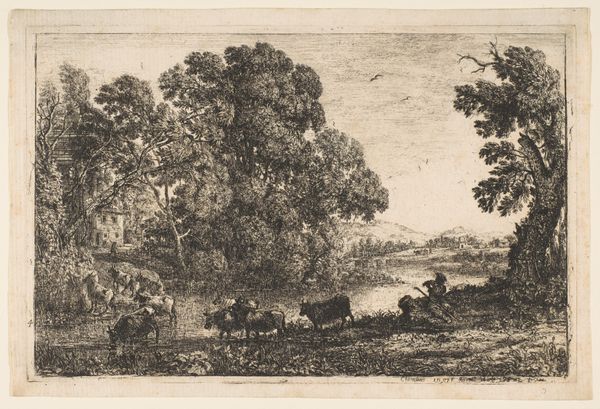

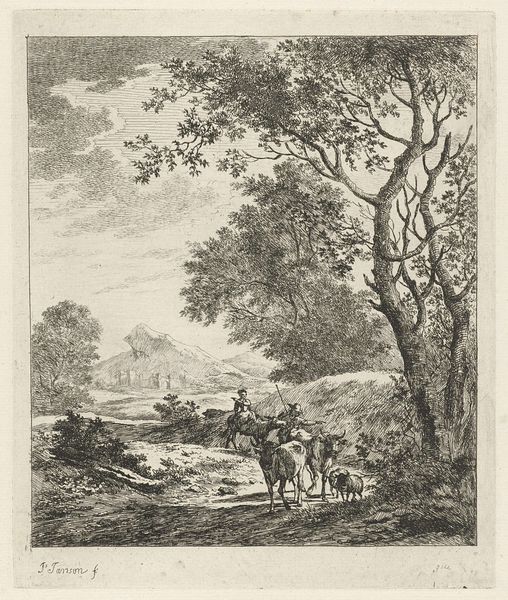

drawing, print, etching, plein-air, paper

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

plein-air

#

landscape

#

paper

#

romanticism

#

france

Dimensions: 136 × 254 mm (plate); 277 × 358 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This is "Marsh with Stags," an etching by Charles François Daubigny, created in 1845. It resides here at The Art Institute of Chicago. What's your initial read? Editor: Brooding. There’s a distinct contrast between the velvety darkness of the foliage and the open sky. A stillness, broken only by the implied motion of the stags. Curator: The composition is meticulously balanced. Note the layering of textures achieved through varying densities of line work—see the willow trees’ delicate, hanging branches that contrast sharply against the denser trees behind the pond. Daubigny's skill with etching is evident in the precision of his mark-making, wouldn’t you say? Editor: Absolutely, but this technical brilliance cannot be separated from its social and cultural implications. Think about the historical context: rural France during the 1840s, on the cusp of immense socio-economic changes. Daubigny depicts a pastoral scene, seemingly untouched by modernity. Aren't we complicit if we ignore the narratives and struggles of people displaced by land enclosure? Isn't this idyllic landscape hiding something else? Curator: I concede the historical factors at play, but the piece itself uses formal elements to evoke an introspective mood. Look at the reflections in the water; the blurring of reality and reflection invites contemplation, drawing viewers inward. Surely the formal techniques contribute to this end regardless of the social situation that bore the work. Editor: And isn't that inwardness reflective of an elite detachment from the world? Romanticizing rurality as something pure and untouched can serve to erase the very real problems of poverty, injustice and exploitation of the working class. We see so many artists that fall into these traps. Curator: It’s a fair point to suggest the absence of peasants in the work but look closely at the overall use of line and texture – the roughness of the application gives it, if anything, an authenticity. Editor: While I remain critical, I must admit that engaging with the formal aspects of the artwork allows us to better deconstruct its inherent biases. Curator: Indeed. Focusing on the stylistic choices lets us ask harder questions about what, precisely, we might be missing in the landscape of 1845.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.