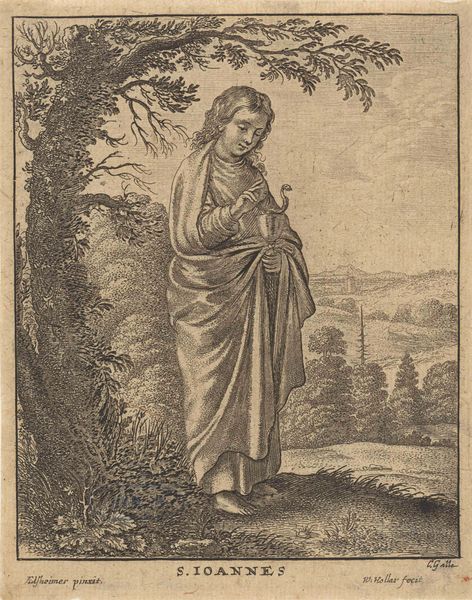

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet: 4 1/2 × 3 7/16 in. (11.4 × 8.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Looking at Wenceslaus Hollar’s "St. John the Evangelist," dated 1650, one notices the incredibly detailed lines created through the engraving process. The composition positions Saint John in a seemingly idyllic landscape, complete with detailed foliage and a distant vista. What captures your attention initially? Editor: Well, first off, the amount of detail achieved through engraving is remarkable, especially the intricate depiction of the natural environment and the saint’s drapery. What stands out to me is that it seems almost like a merging of religious iconography with a broader appreciation for the natural world. How do you interpret that choice? Curator: Precisely. Consider the means of production – engraving, a printmaking technique, makes it easily reproducible. The material—metal plates and the labour to make them—democratizes the image. Was Hollar trying to connect Saint John's narrative to the material world of the everyday person, and what economic factors facilitated that exchange? Note also the way Hollar renders the folds of St. John’s robes, almost textile-like, emphasizing the labor and material inherent in clothing production during this period. Editor: I see your point about reproduction and labor. Is there perhaps a commentary on the commercialization of religion happening? How might Hollar have perceived the relationship between religious devotion, material culture, and emerging market economies? Curator: I think there is. But look again. How is the cup and serpent rendered? Consider that engraving relies on labor intensive technical skill and its contrast to the message in the image? The choice of the medium affects and perhaps alters its reading, right? Editor: That’s fascinating. Thinking about it this way makes me consider how the medium itself adds to the meaning, almost as a comment on the production and consumption of religious imagery at the time. I’ve never thought of it in terms of labour before. Curator: Precisely. This is more than religious iconography; it’s a testament to the process, the materials, and the economic underpinnings of art production in the 17th century.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.