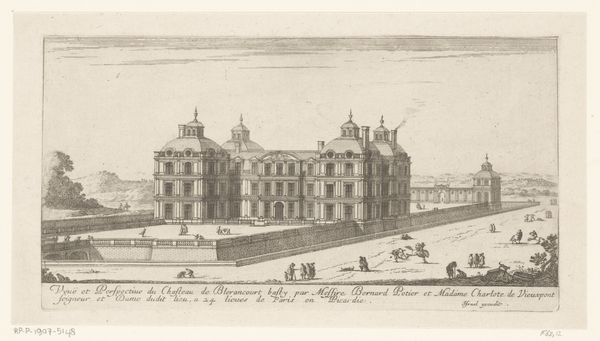

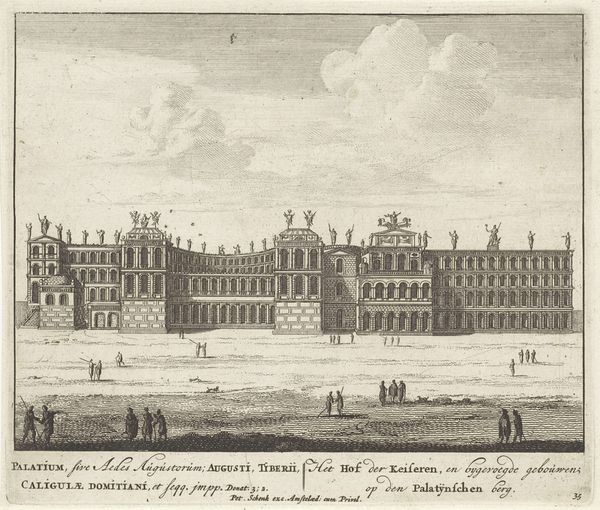

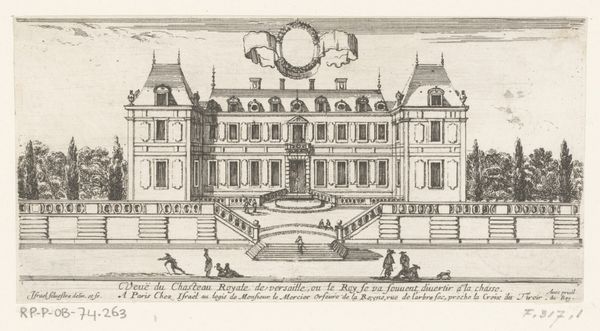

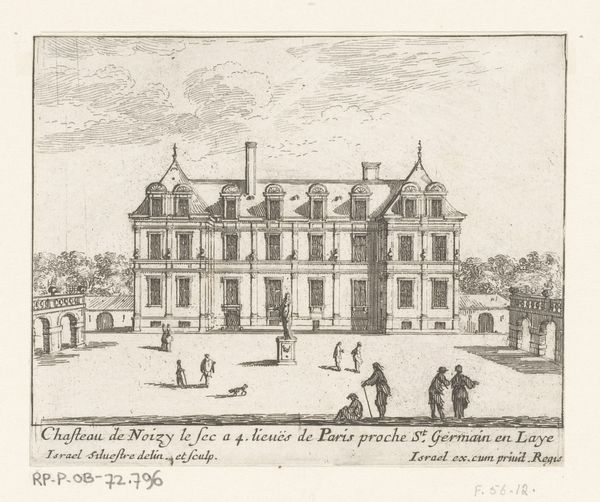

print, engraving, architecture

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

cityscape

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 171 mm, width 205 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Carel Allard's print, "Paleis Honselaarsdijk van achteren gezien," dating from around 1689 to 1702. It’s an engraving of the Honselaarsdijk Palace, showing the rear facade and grounds. What strikes me is the contrast between the almost clinical detail of the palace itself and the rather looser depiction of the figures in the foreground. How do you approach this image? Curator: From a materialist perspective, let's consider the socio-economic conditions surrounding this engraving. The Baroque style speaks to the power and wealth concentrated in the Dutch elite. The printmaking process itself is crucial: copper engraving allowed for the mass production and dissemination of images, serving to communicate power structures. Consider, who was the intended audience? And what kind of labour would have gone into making it? Editor: So, rather than just seeing it as a picture of a palace, you see it as a manufactured item that speaks volumes about social relations. Was there a significant printmaking industry at the time? Curator: Absolutely. The Dutch Republic was a major center for printmaking. Prints like these served various purposes, from documenting architecture to circulating political ideas and fashion. Look at the quality of line – the artisan skill involved! It signifies the availability of trained labour. The palace represents consumption; the engraving its mode of dissemination. Is the function to promote pride in architectural achievements or make accessible exclusive spaces and symbols? Editor: That's a really interesting point. I hadn’t thought about the way that printmaking itself plays a role in reinforcing the palace's status. I see now how this print becomes a material object interwoven with political and economic factors. Curator: Precisely. It's about recognizing the print not merely as an artistic creation but as a product of a specific historical moment, shaped by material conditions and power dynamics. And this consideration allows us to deconstruct its apparent straightforwardness. Editor: This changes how I see art – less about pure aesthetics and more about understanding art as part of a larger material world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.