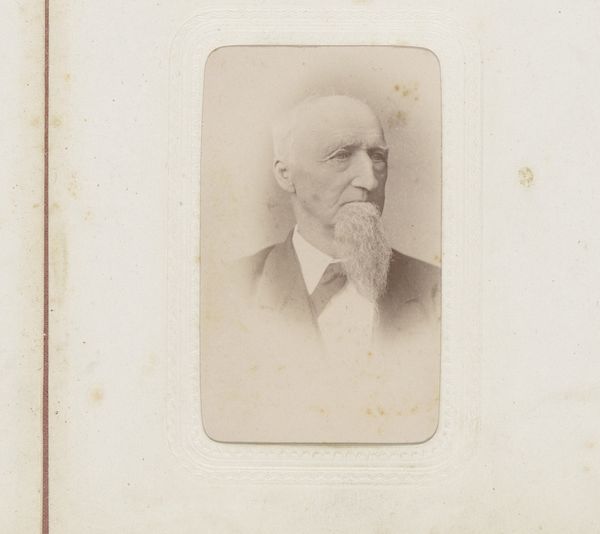

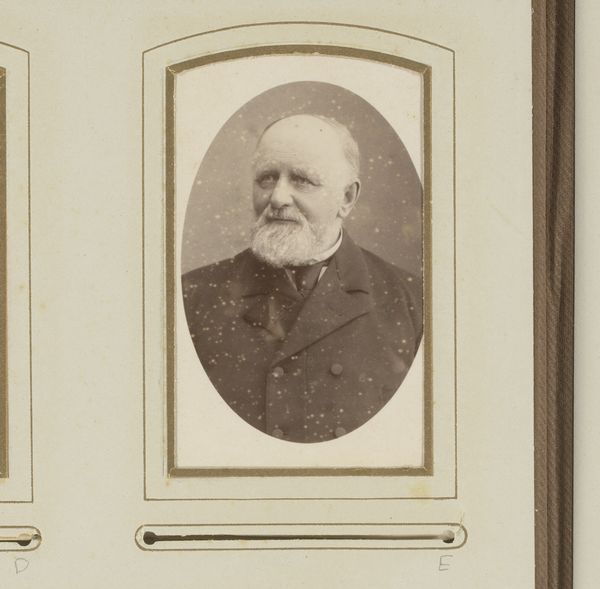

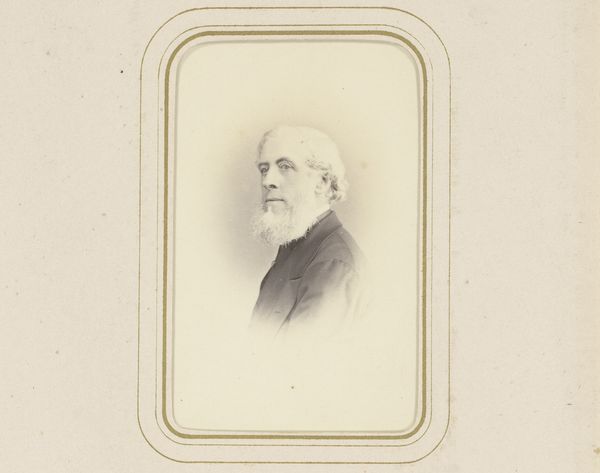

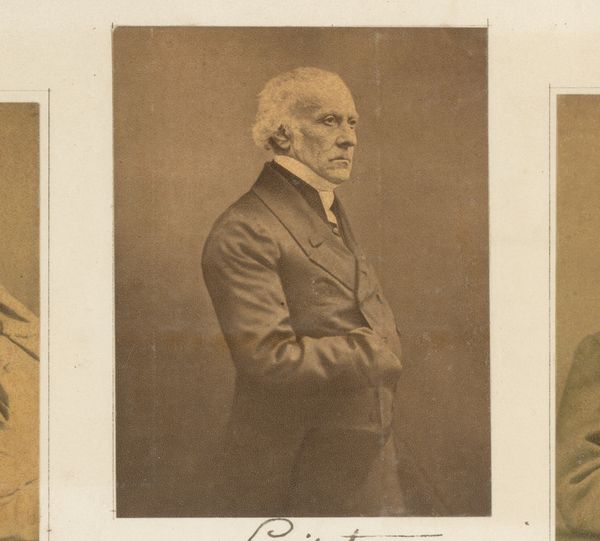

Portret van Herman Christiaan van Hall, hoogleraar in de faculteit Wis- en Natuurkunde aan de universiteit van Groningen 1864

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

Dimensions: height 94 mm, width 60 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This gelatin-silver print, created in 1864 by Johannes Hinderikus Egenberger, is a portrait of Herman Christiaan van Hall, a professor at the University of Groningen. Editor: There's such a solemn quality to this portrait. He seems like a very serious man. I immediately notice his attire: that high collar looks so restrictive. It must have been part of the visual language of authority in his time. Curator: Precisely. Consider the burgeoning field of photography in the mid-19th century and the labour involved. Each gelatin-silver print necessitated careful preparation of glass plates, a light-sensitive emulsion, and controlled development processes. Creating these images was both time-consuming and costly, thus imbuing the sitter with a certain degree of importance. It signifies Van Hall's social standing and the value placed on scientific authority. Editor: The angle of the light is intriguing. He’s almost luminous. And, I am drawn to that tiny area where it is subtly blurring on his collar...It softens the photograph, somehow, suggesting an openness, even vulnerability, beyond the stern professorial image. The gaze, though direct, doesn't feel challenging. Curator: True. Moreover, it’s vital to acknowledge that this portrait wouldn't have been readily available to the masses. The cost and complexity of photographic processes meant its circulation was primarily amongst those of higher social standing and influence within academic and governmental circles. Editor: It also speaks of cultural memory: photographs of figures like van Hall would serve to solidify their contributions within a developing academic and scientific world. The portrait becomes more than just an image; it becomes a stand-in for progress. He is a figure for scientific achievement. Curator: A telling point. Ultimately, looking at a portrait like this reminds us of how much effort went into image creation then versus now. There's a human connection to this portrait that mass reproduction techniques obscure. Editor: I see him more as a man being rendered as an emblem of intellectual prowess for posterity through this technology that was in itself emerging as emblem of the era's fascination with knowledge. It is interesting to consider how that initial intention plays out to us today, looking at him now through very different technology.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.