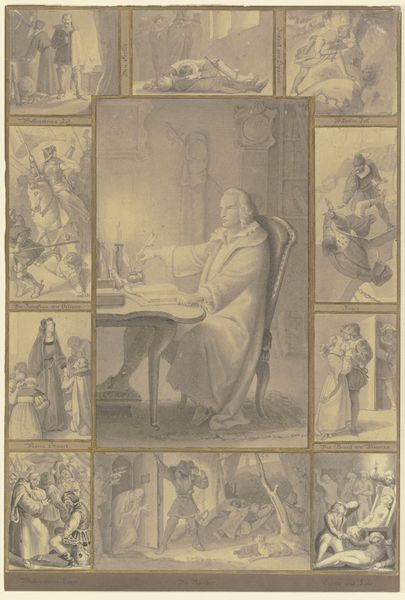

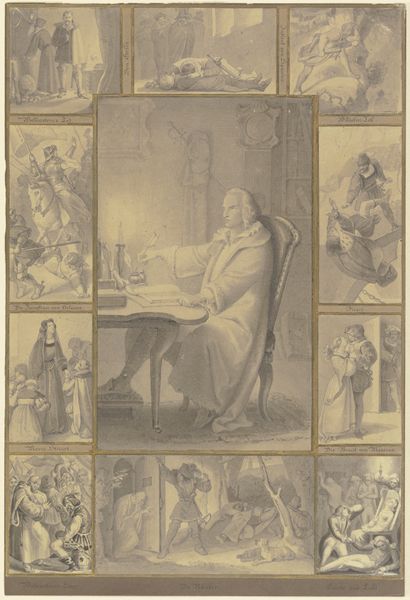

drawing, paper, watercolor, ink

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

paper

#

watercolor

#

ink

#

romanticism

#

watercolour illustration

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

Copyright: Public Domain

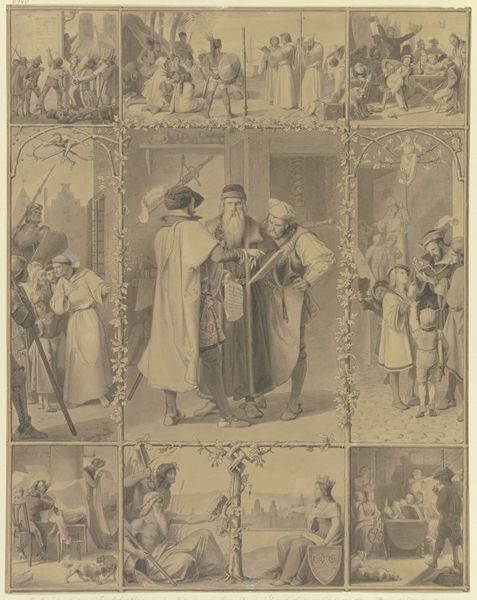

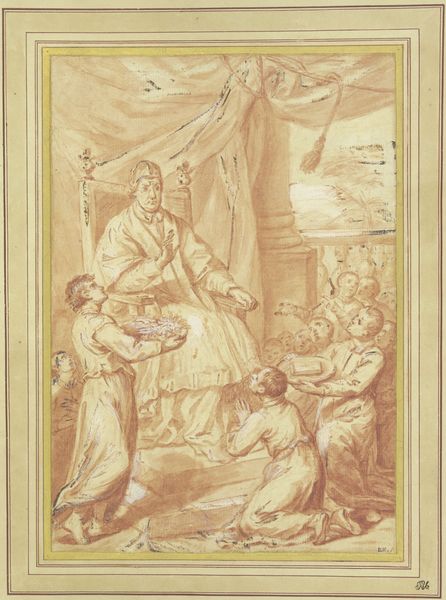

Editor: This drawing, entitled "The Robbers" by Alfred Rethel, features ink, watercolor, and paper. It strikes me as both serene and deeply unsettling. We have this calm central figure surrounded by these violent vignettes. What can you tell me about it? Curator: This piece encapsulates the Romantic era's fascination with history and narrative, but also reveals the inherent power dynamics in how those narratives are constructed. We see the writer at the center, illuminated, presumably the author of "The Robbers" play, surrounded by scenes of his creation. Editor: So it’s almost meta, like the artist commenting on the power of storytelling? Curator: Precisely. Think about who gets to tell the stories, and whose perspectives are privileged. Rethel positions the author as a central figure, literally and figuratively. The author mediates the world for us and gives the scenes life through literature, doesn’t he? Editor: Yes, but it seems to celebrate a turbulent history. Curator: It also subtly questions the morality and lasting impact of glorifying such chaos, by framing each scene of the literary masterpiece. Romanticism often grappled with such contradictions, showing history, not just as fact, but as interpreted action through artistic agency and sociopolitical powers. It makes you wonder, doesn’t it: what public role are we to give the stories that illustrate chaos? Editor: That's really insightful! I hadn't considered the framing as a form of critical commentary. I see it differently now, as the artist asking the public: “how are we framing art’s role”? Curator: Exactly! Art doesn't exist in a vacuum. It is always shaped and interpreted through the lens of the societies that produce and receive it. I now think I know a little more, from this, about how museums themselves should perhaps frame it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.