painting

#

portrait

#

figurative

#

portrait

#

painting

#

portrait subject

#

portrait reference

#

portrait head and shoulder

#

portrait drawing

#

genre-painting

#

facial portrait

#

academic-art

#

portrait art

#

fine art portrait

#

realism

#

celebrity portrait

#

digital portrait

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

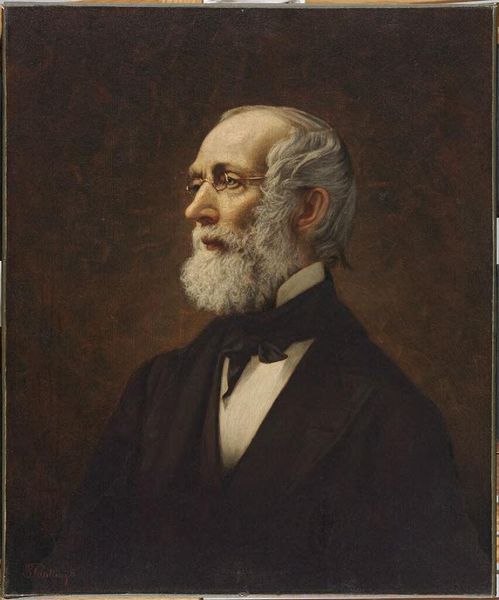

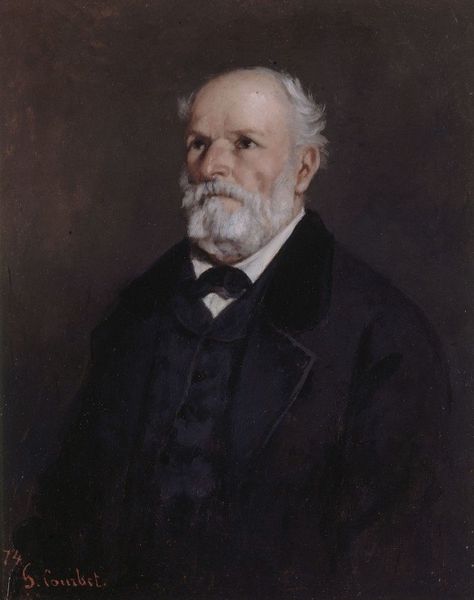

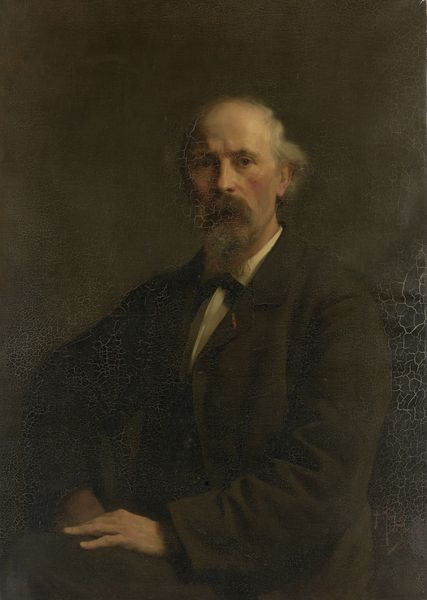

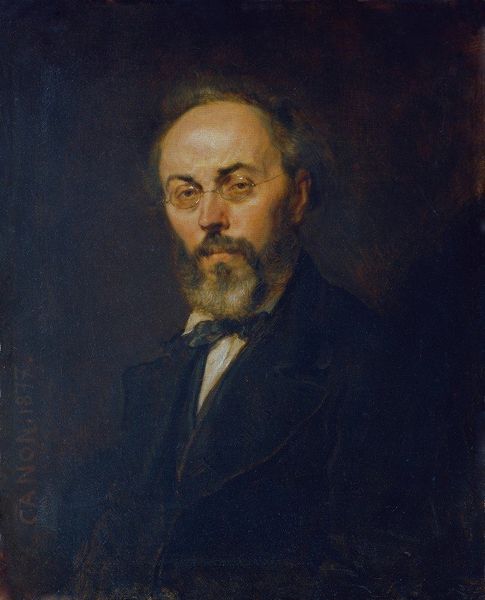

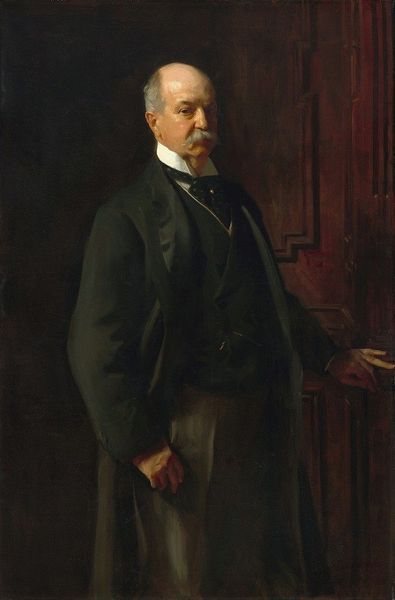

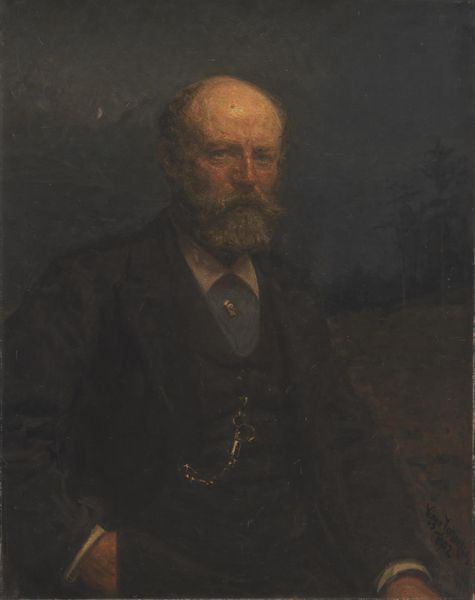

Editor: This is Gyula Benczúr’s “Portrait of Koŝice Banker Fiedler,” painted in 1864. I'm immediately struck by its classical feel – almost like a Roman senator. What do you make of it? Curator: Absolutely, the composition leans heavily on the visual language of power and status, which can lead us to examine its function within 19th-century Hungarian society. He is not a Roman senator, but he might as well be in terms of status! Considering that the sitter was a banker, what narrative does the artist create around wealth and social mobility? Editor: So it’s about legitimizing the role of the banker, by visually associating him with this established tradition? Curator: Precisely! Think about how newly wealthy bourgeois families sought to assert their place within existing hierarchies. The portrait became a powerful tool. What kind of rhetoric emerges when artists borrow from aristocratic, even ancient, visual tropes? Consider the hand gestures and that imposing architectural column. They're doing more than just showing us what this man looked like, don't you think? Editor: I see your point. It’s using those established symbols to give the banker a certain kind of...authority? Like he's always belonged there. It almost masks any tension related to rising new powers. Curator: Yes, the portrait obscures that social disruption through visual strategies of power and belonging. Who is being excluded by these symbols, who has access to these halls of power, and what might a counter-narrative look like? Editor: This makes me think about how portraits even today work to project certain identities and power structures. It's never just about capturing a likeness. I’ll definitely view such pieces with different eyes moving forward! Curator: Exactly! We must learn to question which voices and perspectives are represented and which are suppressed. The more we engage, the better we understand the story being told and whose interest is really being served.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.