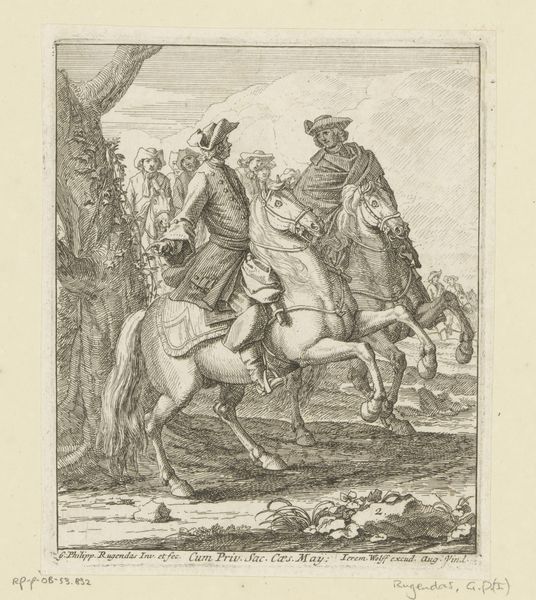

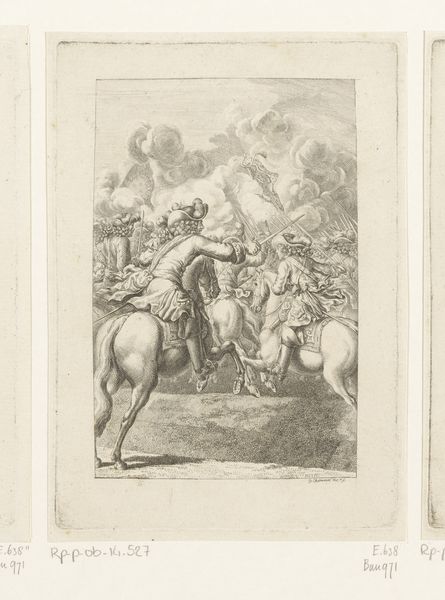

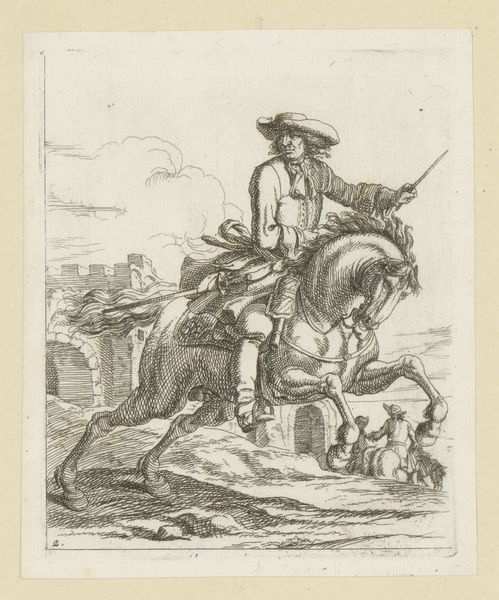

Steigerend paard met ruiter, gevolgd door soldaten te voet en ruiters 1676 - 1742

0:00

0:00

georgphilipprugendas

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 164 mm, width 136 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us, we have "Steigerend paard met ruiter, gevolgd door soldaten te voet en ruiters" – or "Rearing horse with rider, followed by soldiers on foot and horsemen" by Georg Philipp Rugendas, an engraving dating from somewhere between 1676 and 1742. It's part of the Rijksmuseum's collection. Editor: Immediately, there’s this almost frantic energy, despite being a static image. The rearing horse creates a focal point, but it’s less about triumph and more about perhaps, impending conflict. There's an anxiety in that upward motion. Curator: That’s interesting. Considering Rugendas’ broader body of work—prints documenting military campaigns—one could interpret this moment as a crucial decision point within a larger theater of war. Look at the medium itself, this engraving – multiple identical images can be produced, for mass consumption and distribution to promote the valor, but also maybe the legitimacy, of the war. Editor: Exactly. And look at who's being represented and how. We see the privileged, embodied in the horseback rider with the fine garb leading the charge. But at what cost? The soldiers on foot, obscured, somewhat, nameless figures who, while supporting the military goal, occupy a significantly different societal position. Curator: True, but it's also a document of craftsmanship. Consider the detail achieved through the engraving process. Look closely, you can discern the textures of fabric, the musculature of the horse… even the fleeting expressions on the soldiers faces are clearly delineated. It speaks to a skilled artisan, even if that skill served to create martial propaganda. Editor: And doesn't that reinforce the issues? The beautiful execution highlights how skills and materials are conscripted for power structures. What stories don't we see here? What about the civilians, the people affected by these military exploits? It becomes a poignant reflection on who is memorialized in historical depictions and by what criteria. Curator: Indeed. It challenges us to consider not only the "what" of historical representation, but also the "how" and "why". What processes are undertaken and whose agendas are ultimately advanced? Editor: Right. Analyzing representations like these makes us rethink assumptions about the recording, memorialization, and perhaps, glamorization, of historical conflicts. I guess I'm left wondering, too, about where, today, we continue to see this use of printing processes employed for ideological narratives and social control.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.