paper, photography, albumen-print

#

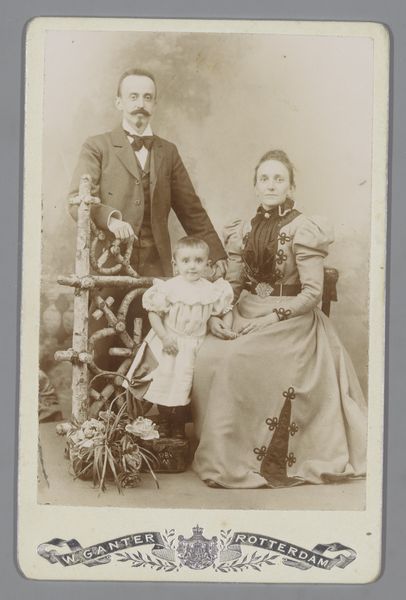

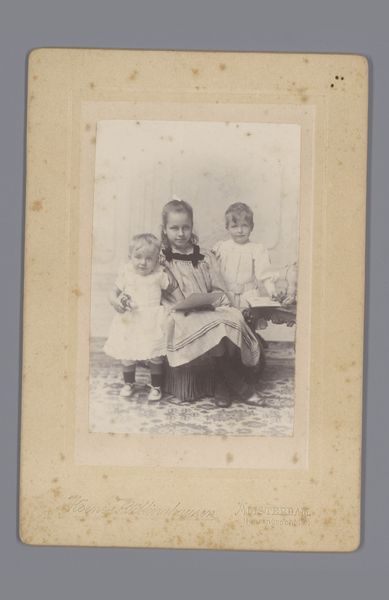

portrait

#

aged paper

#

paper

#

photography

#

child

#

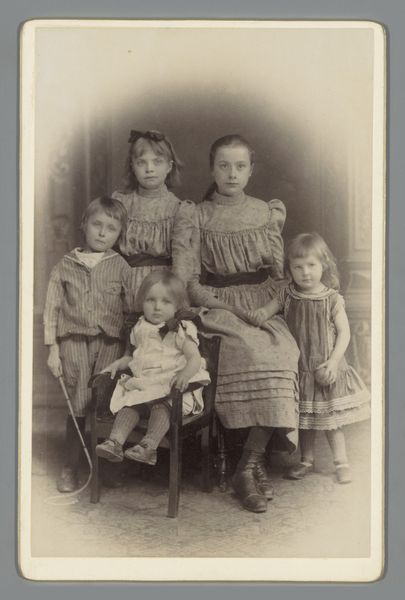

group-portraits

#

paper medium

#

albumen-print

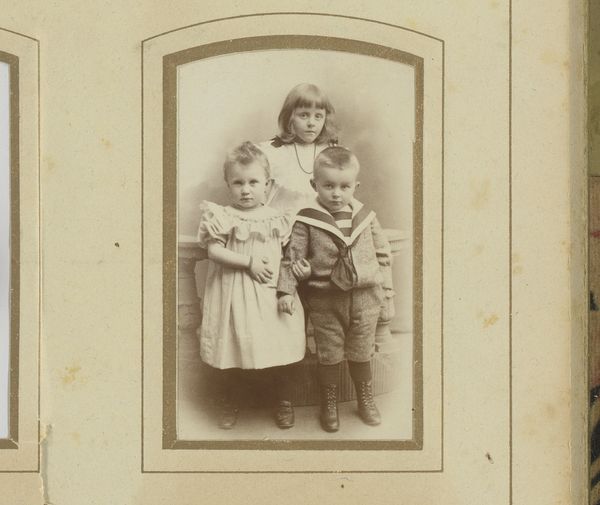

Dimensions: height 101 mm, width 63 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

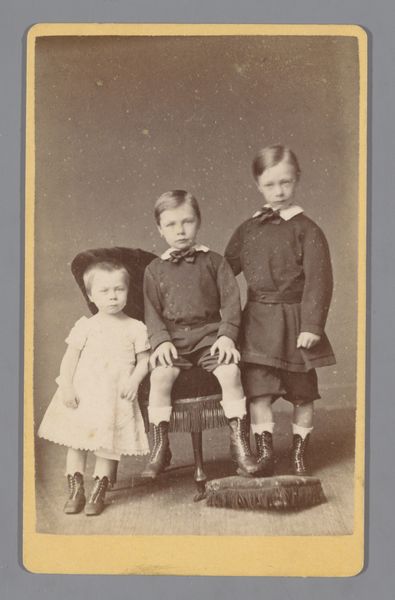

Curator: Looking at this intriguing piece by Weijert Jan van Zanen, titled "Portret van een onbekende jongen, baby en een meisje," created somewhere between 1893 and 1913 using albumen print on paper, my mind wanders. Editor: It immediately strikes me as an object of the past. Seeing that the medium is aged paper, it raises interesting questions about how that decay affects our reading of the image. Curator: Absolutely! It's as if the past is gently nudging the present. I sense a hushed solemnity in their eyes. I wonder what their world was like. The composition—a baby cradled almost centrally, flanked by what seems to be older siblings—hints at hidden narratives. I’m wondering: could it have been for commemoration purposes, possibly following a loss? Editor: Right, that backdrop, the elaborate posing... it's theatrical, but for whom? We have to think about the audience for these things back then. Photography was often a privilege, a way for a burgeoning middle class to present itself. What was involved in acquiring the photographic paper, preparing the chemicals, and constructing the space of representation in the photographer's studio? How would those means affect how class might be portrayed? Curator: Ah, yes! It brings up the economics of family portraiture at the time, and the very conscious act of constructing and freezing a moment in time. It begs questions: Is it their authentic selves on display? Or the clothes of their class? Is this not another brick to the foundations of family values that dominated Western society? It’s an intriguing display of bourgeois staging! Editor: Exactly. We need to peel back the layers. Who profited from this transaction? How does this relate to the mass production of images in the late 19th century and its effects on identity formation? It's all tangled up: economics, social standing, the physical properties of albumen… even the way light behaves on that coated paper contributes. Curator: Indeed. Considering the context – photography becoming more accessible yet still a deliberate undertaking – I now imagine the weight each child must have felt during the sitting. A world frozen in time, and all those hidden struggles now lost. Editor: Looking at the piece, thinking about the labor behind the scenes, I get a real sense of the complicated history of making and showing that images embody—not just the sentimental value. Curator: Agreed. Thank you for shedding a practical, alternative, almost material light, I think that it has encouraged a more multi-faceted response.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.