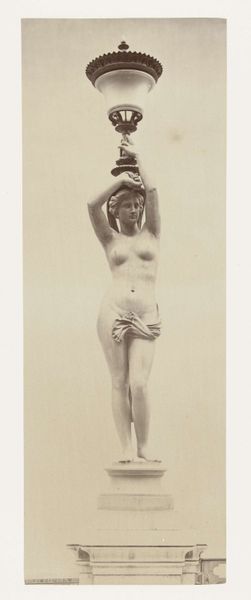

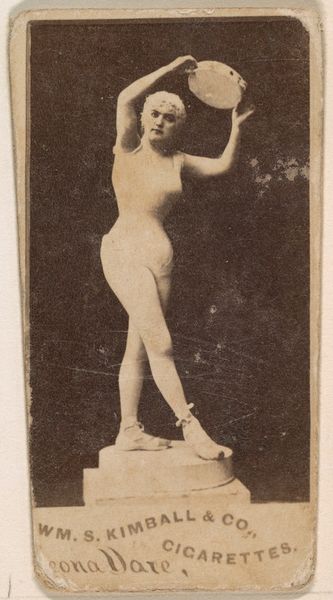

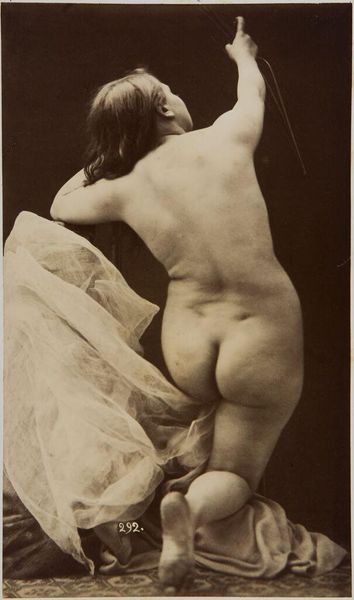

Vloer lantaarn in de vorm van een naakte dame, zij houdt op haar hoofd een kelk vast. c. 1878 - 1881

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: height 375 mm, width 230 mm, height 620 mm, width 438 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a photograph from the late 1870s or early 1880s by Louis-Émile Durandelle, titled "Vloer lantaarn in de vorm van een naakte dame, zij houdt op haar hoofd een kelk vast" — that's "Floor lamp in the shape of a naked lady, she holds a chalice on her head" for our non-Dutch speakers. The work is, fittingly, a study of a bronze sculpture functioning as an ornate floor lamp. Editor: The first word that jumps to mind is "burden." She looks so somber, dutifully carrying this heavy light. Does the illumination she offers justify the… exploitation of her form? Curator: Well, that's an interesting take, particularly as we consider this within the historical context of Neoclassicism and the prevalent Orientalist themes in art at the time. We're seeing the objectification of the female form, sure, but it’s also an example of the industrial arts moving toward mass production—sculptures, once precious, being made for everyday bourgeois consumption. Consider the foundry that produced it; how did those labourers understand the original artistic intention, and did their own investment of physical labor shape its significance? Editor: The photograph itself lends an interesting layer of mediation too, doesn't it? The almost monochromatic quality makes the texture of the bronze palpable but also creates distance. And speaking of burden… do you think it’s possible to look at her offering of light as generous, even transcendent, not merely exploited? What kind of interior space was lit up by such a thing, and was there any beauty in that practical reality? Curator: Perhaps the sculpture’s intent, though, can only be grasped fully when also examined as part of broader visual trends, production processes, and commercial considerations… The interplay between the artist, the craftspeople who realize the artist's design, the vendors selling lamps such as these. These sculptures—especially rendered via photographs—democratized the aesthetic values and tropes of a class… Editor: It's a dizzying piece in some ways, because it pushes and pulls at my empathetic senses so. There's this strange mix of the classical and the frankly, sort of, gaudy... It throws you, doesn’t it? Curator: Indeed. By focusing on the various dimensions of production and social context, we can move toward an insightful comprehension. Editor: A light of surprising density.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.