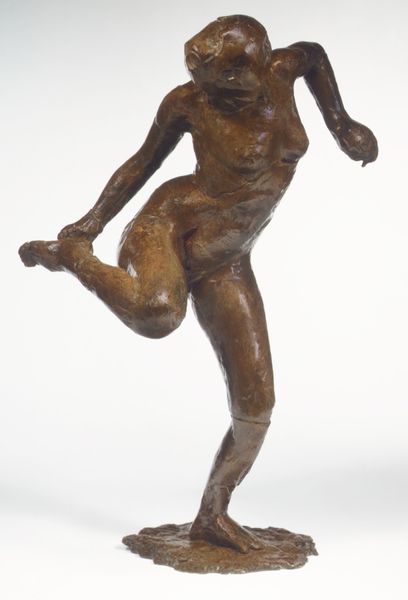

Dimensions: 16 x 10-1/2 x 9-3/4 in. (40.6 x 26.7 x 24.8 cm.)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Looking at "Arabesque Devant," a bronze sculpture by Edgar Degas created between 1878 and 1920, on display here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, one immediately senses a dedication to capturing a fleeting moment. Editor: Absolutely. I find her stance so powerful and defiant, almost heroic, though the bronze feels simultaneously fragile, particularly at her standing foot, so expressive! There is strength in it. How interesting that the bronze seems like a material of contradiction. Curator: The bronze, of course, presents a fascinating dialogue within Degas's oeuvre, especially when considering his interest in depicting ballerinas. This work allows us to reflect on the socio-cultural forces impacting the representation of female performers at that time, focusing on the often rigid expectations imposed upon their bodies and their movements within institutions like the opera and ballet. Editor: Those constricting forces really play out, don't they, in how ballet dancers are perceived, both idolized and objectified? What can Degas tell us about the objectification of women in ballet during that time period? Her nudity makes me think about this. And what kind of class position must one be to become a ballet dancer in 1878? What if this had been rendered of a male? It poses an interesting question on gender roles. Curator: Right. This sculpture allows us to examine those ideas in relation to art. It acts as a signifier for these tensions—the tension between athleticism and artifice, expectation, the vulnerability that comes with performance—that shaped the lives and experiences of these women. We see the political and social play out within. Editor: That resonates. And seeing her as an isolated bronze figure also intensifies the drama surrounding her. This single arabesque now carries a hefty load of narratives. It also is nice to note the ways ballet costumes can limit some of the narratives of class differences between the male gaze on bodies performing versus bodies toiling and working. How does Degas’ focus make one look more at one group than the other, or think of that connection at all? I suppose both do perform labor for money. Curator: A striking example of art's ability to simultaneously embody both beauty and the complexities of historical power dynamics. Degas provides an entryway, that once parsed can reveal complexities of body, power, and class that resonate deeply today. Editor: I agree, such conversations make experiencing it all the richer.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.