Afriquaine, en deshabillé, plate 97 from "Recueil de cent estampes représentent differentes nations du Levant" 1714 - 1715

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

islamic-art

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet: 16 5/16 × 12 1/8 in. (41.5 × 30.8 cm) Plate: 14 1/8 × 9 13/16 in. (35.8 × 24.9 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

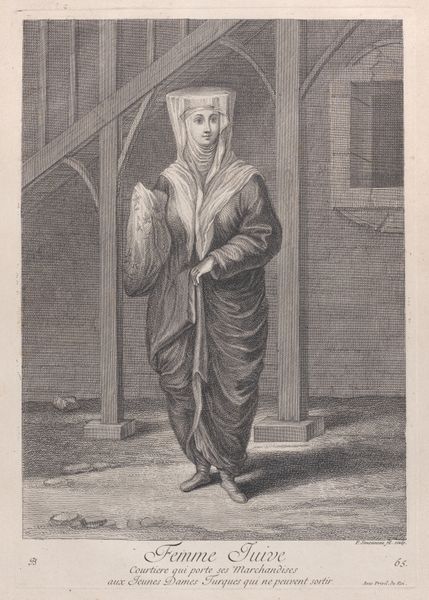

Curator: This print, titled "Afriquaine, en deshabillé" or "African Woman, Undressed", plate 97 from "Recueil de cent estampes représentent differentes nations du Levant", was created between 1714 and 1715 by Jean Baptiste Vanmour. It's an engraving. Editor: Immediately, I’m struck by the contrasting textures Vanmour achieves with just line work. The draped fabric has this wonderful weight, almost like velvet, compared to the flatness of the wall behind her. Curator: The “weight” you perceive speaks volumes about 18th-century European perspectives on the "Levant," or Ottoman Empire. Vanmour, as court painter in Constantinople, was commissioned to produce images which served as both documentation and promotion of the exotic "other" for wealthy European consumers. The printmaking industry allowed for wide dissemination of these colonial-era images and fantasies. Editor: Setting aside its colonial context for a moment, the composition is quite clever. The subject's contrapposto stance gives dynamism, offsetting the static backdrop, the lines lead us to her face, where her expression conveys this captivating mixture of availability and self-possession. Curator: Availability for whose consumption though? These images served specific economic and political purposes. The artist had access to particular spaces and communities mediated by diplomatic networks. Even the paper itself speaks to the means of production and trade relationships of the era. We are dealing with a construction, not necessarily a faithful representation, which fed into orientalist tropes of the time. Editor: I don’t disagree with your points about the print’s intent, yet its execution shows close observation and the subtle modelling, use of light and shadow, give form to this idea; also this very fine hatching really evokes the soft fabrics and bare skin that make it much more complex than simple propaganda. Curator: Certainly, technical skill is evident. But considering the socio-political landscape in which it was made, it prompts essential conversations around power dynamics. It’s through acknowledging those histories and labor practices that we can start critically unraveling its charm. Editor: A valuable point. So it seems the intersection of form and the artwork’s social creation generates compelling readings. Thanks for sharing.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.