Monatsbild September, oben mittig das Zeichen der Waage c. 1622

0:00

0:00

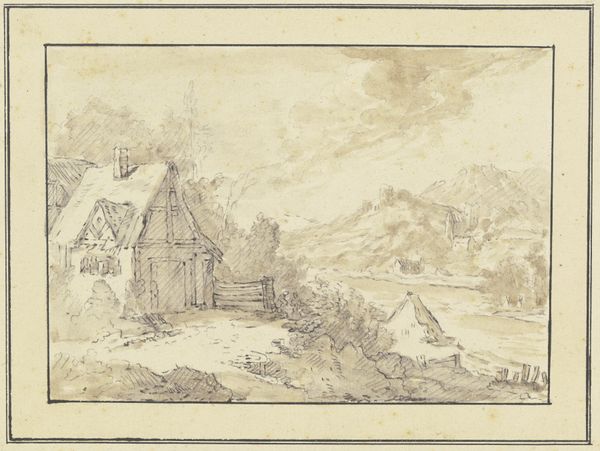

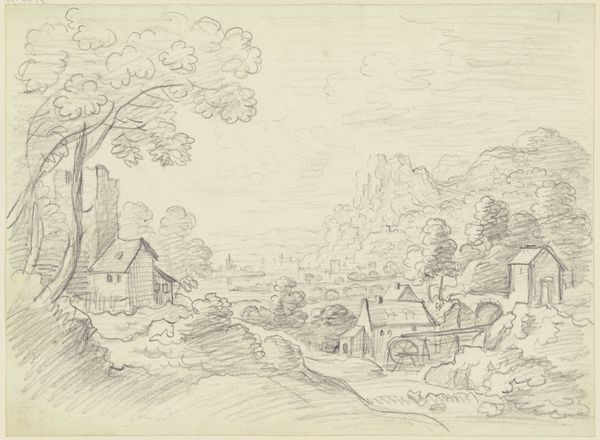

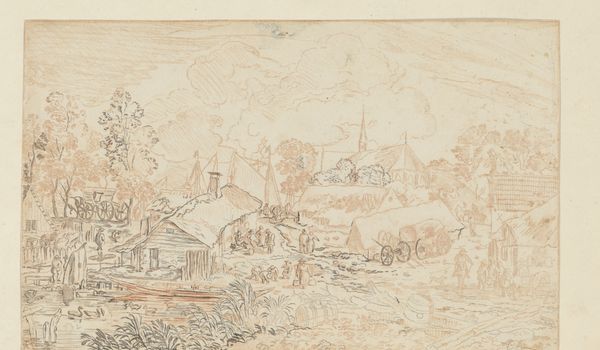

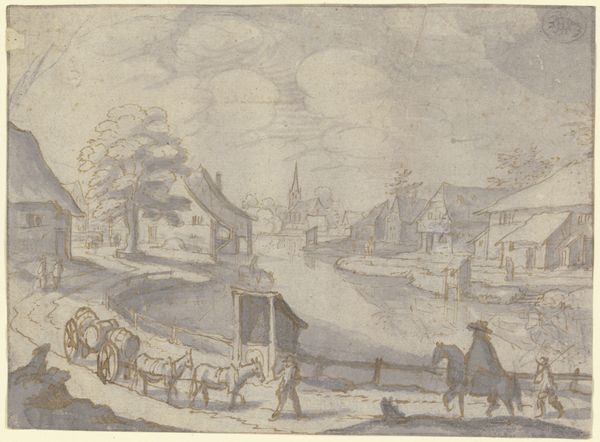

drawing, paper, watercolor, ink, chalk

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

landscape

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

watercolor

#

ink

#

coloured pencil

#

chalk

#

cityscape

#

watercolor

Copyright: Public Domain

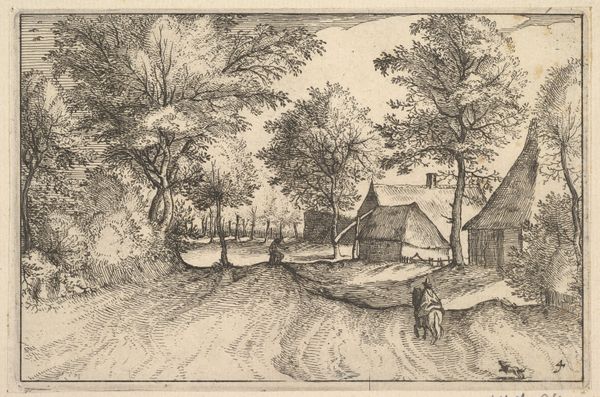

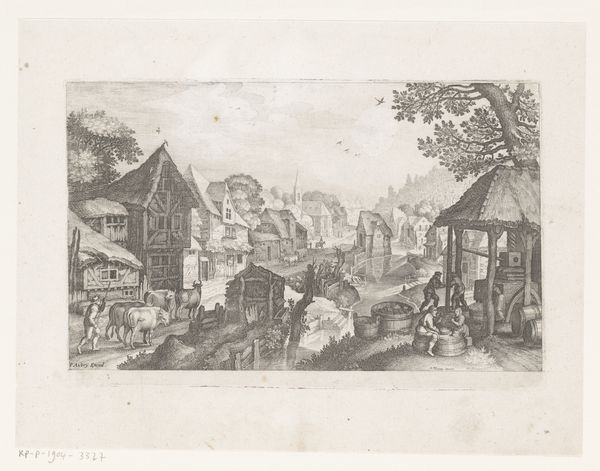

Curator: Looking at this work, "Monatsbild September, oben mittig das Zeichen der Waage," by Matthäus Merian the Elder, dating back to about 1622, what's your initial impression? It’s currently housed in the Städel Museum. Editor: It's...muted. The grey wash gives it an aged, almost melancholy feel, even though it's ostensibly a genre scene. The whole composition, with that little Libra symbol floating above, has a strange, almost fatalistic calm. Curator: The process and materials definitely contribute. It's ink, watercolor, chalk and colored pencil on paper. Merian's technique really showcases how those base materials can depict an entire community laboring through the late summer days. Consider the artisanal production of paper in the 17th century and how the pigments are derived. These processes are far from neutral; their extraction shapes social relations. Editor: Absolutely. And beyond the technique, there's the symbolic representation. These monthly images historically served the ruling class as indicators of time and, in turn, of their dominion over their laborers. Do you see, as well, the figures engaged in this everyday agrarian labor? How their bodies seem as weathered as the landscape itself? And how might the Libra symbol overhead speak to early modern concepts of social balance and justice--or perhaps the *lack* thereof, the scales perpetually in need of adjusting? Curator: That tension is compelling. I’d also like to point out the level of detail rendered within such a small-scale artwork. Look at the texture of the buildings and the animals-- rendered with chalk. The artist is not simply sketching a landscape. He is showcasing the artisan’s mastery of the artistic media. The means of production of images has socio-economic and representational dimensions we shouldn't disregard. Editor: Exactly! And by understanding the socio-economic underpinnings, we expose whose stories often go unseen. Who produced the actual milk? How was labor valued based on gender? By questioning these imbalances, the art becomes a platform for re-evaluation, for advocacy, even in its seemingly quaint presentation. Curator: Thinking about this piece has clarified something: seeing labor visualized and humanized here helps dismantle preconceived notions. We are not seeing royalty or important figures, only day-to-day workers, and their treatment needs to be continuously contextualized in any artistic interpretation. Editor: It’s prompted me to reflect on the way art history too often glosses over those quieter narratives of inequity in the service of aestheticizing power. This is the beginning, no? We are called to look beyond what’s pretty, and look at what's *present*.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.