painting, oil-paint

#

baroque

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

history-painting

Dimensions: 74 cm (height) x 41 cm (width) (Netto)

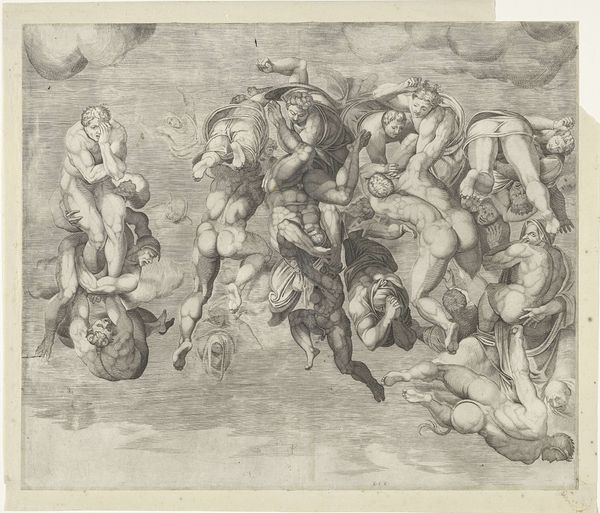

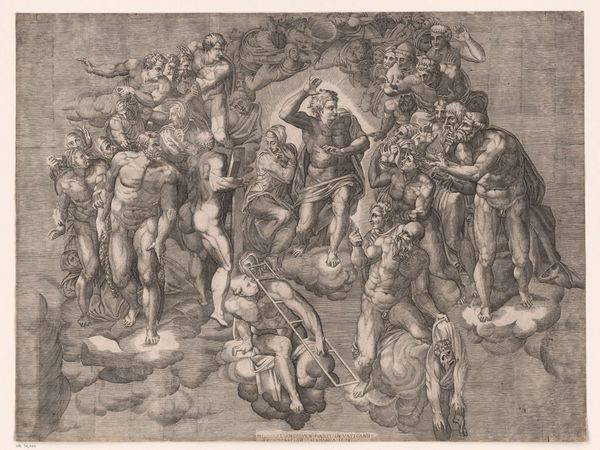

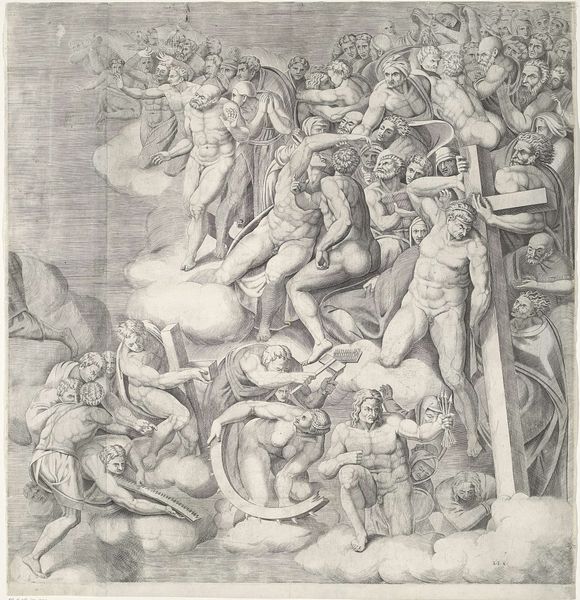

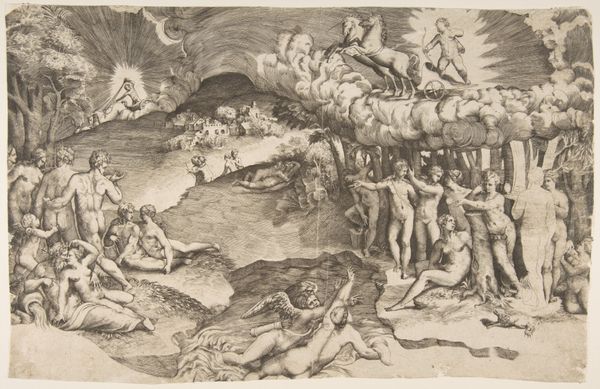

Curator: Eugenio Cajés's "The Fall of the Rebel Angels," painted in 1605, offers a dramatic vision of divine retribution, wouldn't you agree? Editor: Woah! Total chaos, right? It's like a heavenly mosh pit, but instead of joyous sweat, it’s fire and eternal damnation! The composition, with its tiers, feels… weighty. Curator: Weighty is a great word. The hierarchical arrangement, you see, reflects the strict order of the cosmos in medieval and early modern thought. Angels ascending towards divine light, balanced by the tumbling mass spiraling into darkness. This reflects the psychological weight associated with sin. Editor: And what a spiral! It's almost sickening, the way those figures are contorted. Reminds me a little of how history sometimes seems to repeat the same terrible scenes. The faces—distorted with fear and regret—it's too real for me. I get what the Baroque is all about now, huh? Curator: Precisely! The Baroque sought to elicit strong emotions through dramatic compositions and dynamic movement, and Cajés is a wonderful exponent of this style. Angels and devils in this canvas become vessels for ideas and cultural trauma concerning religion. What does it convey to you? Editor: A primal scream bottled in oil paints, maybe. I mean, it's hard not to see humanity in those falling figures. That rebellion and its price seem, I don't know, relevant today. We're always fighting some kind of fall from grace, personal or collective. It's wild how an image from 1605, conjures that, don't you agree? Curator: The universality of that theme has kept it alive throughout history, from Milton's Paradise Lost to the numerous cinematic representations. But Cajés captures not only theological ideas, but how to deal with them as a culture, building memory of a specific topic across time. Editor: Yeah, it's kinda dark to ponder over a coffee. Well, I didn't expect to have such a reflective, religious thought for the morning! Curator: Nor I! An important reminder to look at old art and contemplate what ideas it provides us, in contemporary terms.

Comments

statensmuseumforkunst about 2 years ago

⋮

On a journey to Italy the Spanish artist Eugenio Cajés became acquainted with a new way of observing shadow. Leonardo da Vinci had observed that local colour loses its colour properties when in shadow because the eye finds it difficult to register colours in darkness. Within the realm of art this new knowledge prompted a new mode of painting, the so-called chiaroscuro method (from the Italian for light-dark ness). With the introduction of chiaroscuro artists began to mix the local colour with black to create the pigment used for form shadows. Before this, a fully saturated version of the local colour had been used for shadows. Cajés employed the new manner of painting to evoke a sense of horror in Lucifer's Hell, where flames relentlessly torment the lost souls and rebel angels. Here, chiaroscuro is used to create a contrast to the divine universe at the painting's top, where the Archangel Michael and his host are depicted in pearlescent pastels.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

statensmuseumforkunst about 2 years ago

⋮

Eugenio Cajés takes his starting point in the biblical narrative about the evil angels and their leader, Satan, who were originally part of the heavenly host. Enemies of God and friends of evil, they were eventually cast down into Hell by the archangel Michael. During their fall, vividly depicted by Cajés, the rebel angel sprouted tails, claws and other demonic traits. Cajés became acquainted with a new manner of painting during a trip to Italy, the so-called ‘chiaroscuro’. With the advent of chiaroscuro, artists began mixing local colours with blacks and browns to create shaded areas. Cajés used this new manner of painting to evoke a sense of dread and horror in Hell, creating a contrast to the divine realm at the top where Michael and his army are portrayed in shimmering pastels.