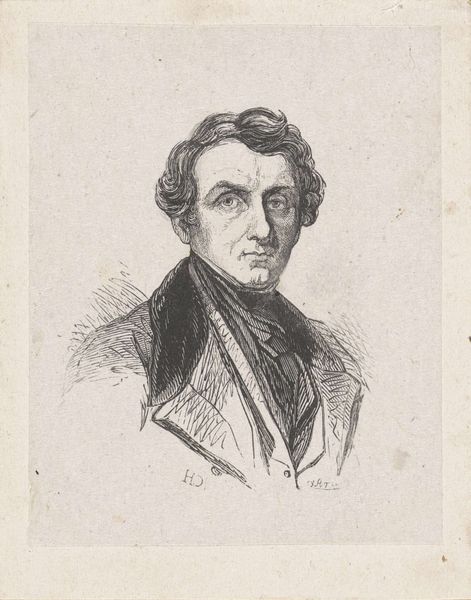

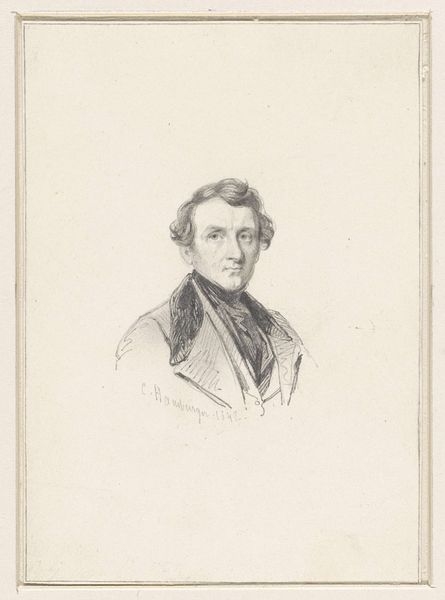

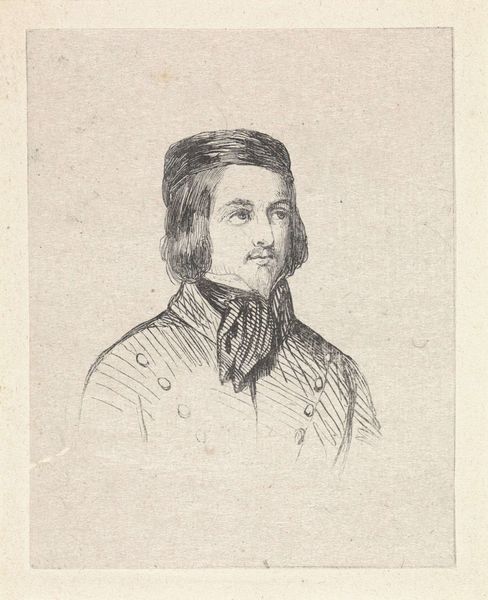

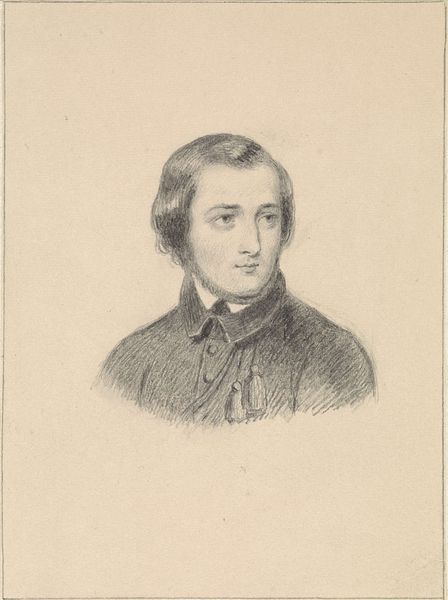

Portret van de schilder Charles Ferdinand Venneman c. 1832 - 1900

0:00

0:00

adolphefredericnett

Rijksmuseum

drawing, pencil, graphite

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

graphite

#

portrait drawing

#

realism

Dimensions: height 88 mm, width 71 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: The subtle tonality of this pencil drawing creates an introspective mood. It feels so personal. Editor: Absolutely. I am immediately struck by the detail achieved with graphite on paper. The hatch marks give such volume to the subject. Let’s talk context. What can you tell us about Adolphe Frédéric Nett's "Portret van de schilder Charles Ferdinand Venneman," dating from around 1832 to 1900? Curator: This work resides here at the Rijksmuseum and gives us a glimpse into the artistic circles of the 19th century. Venneman, as a painter himself, certainly occupied a specific position within the bourgeois class structure of his time. To understand Nett's choice to portray him, we have to examine their relationship in terms of power and influence. Editor: Precisely. And consider the tools available to Nett. Pencils, paper – these were relatively accessible materials, suggesting a democratization of portraiture, perhaps. How did the economics of art production affect who was represented and how? Was Nett commissioned, or was this a more personal project reflecting social bonds within the art world? The varying marks, at times faint and scratchy, suggest that the act of drawing was a deliberate process of labor. Curator: Indeed. It's tempting to speculate about the nature of their collaboration. Was Nett, through this work, aligning himself with a certain artistic philosophy embodied by Venneman? Or was this a comment on artistic status at the time? We must consider how social capital works through portraits like this one. Who is made visible, and by whom? Editor: And who controlled the materials through which representation happened? The very means of production carry cultural information. The subtleties of the hatching suggest it could be argued that the materiality has to convey form, value and even feeling because of its economical, easily transportable mode of production.. It adds an ethereal fragility. Curator: By placing it within our modern theoretical framework, we uncover dynamics perhaps invisible to a contemporary viewer. It is in this re-framing that its full potential as a socio-historical document can be realized. Editor: Absolutely, because when we connect it to its making, it’s brought out of its frame.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.