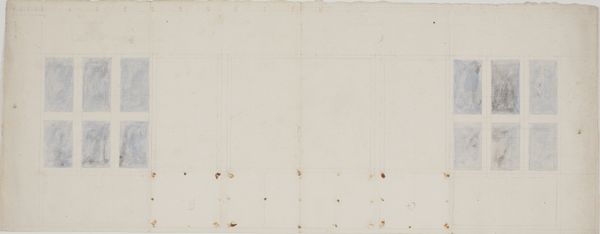

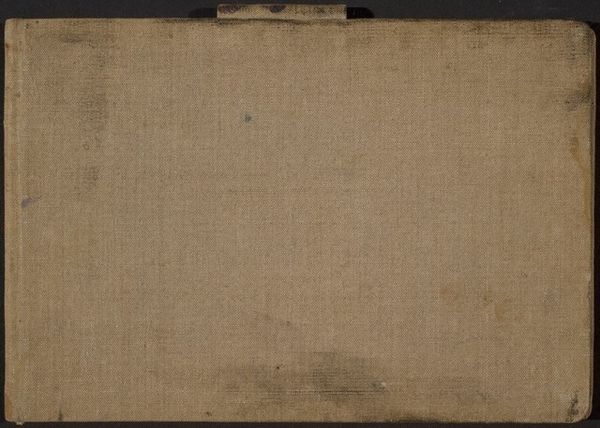

Trompe l'oeil. The Reverse of a Framed Painting 1668 - 1672

0:00

0:00

painting, oil-paint, canvas

#

baroque

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

canvas

#

trompe-l'oeil

Dimensions: 66.4 cm (height) x 87 cm (width) (Netto), 66.6 cm (height) x 86.8 cm (width) x 3.7 cm (depth) (Brutto)

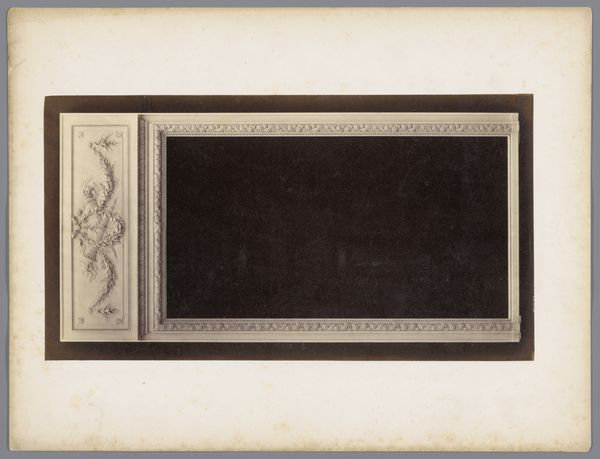

Curator: Here we have "Trompe l'oeil. The Reverse of a Framed Painting," created between 1668 and 1672 by Cornelius Norbertus Gijsbrechts. Editor: My first thought is of deception! It feels like I’m being presented with a truth only to realize it’s an elaborate trick of the eye. The palette seems intentionally muted, almost… spectral. Curator: Absolutely, Gijsbrechts masterfully employs oil paint on canvas to present a *trompe-l'oeil*, literally "deceives the eye," which became popular during the Baroque era. He’s engaging with the artistic conventions of representation, questioning the very act of seeing. What is hidden, and what is revealed, in our encounter with art and illusion? Editor: The back of a framed painting! It makes you wonder about labor – all the unseen effort behind the finished product, and about what’s deemed worthy of display. There’s something deeply democratic, and subtly political, about showcasing this usually hidden reality of art production. It feels almost defiant. Curator: That's astute. Consider that in Gijsbrechts' time, ideas about skill and status were closely linked to patronage. Who gets to look "behind the scenes"? In a way, Gijsbrechts creates a painting that everyone, theoretically, already knows, but is also implicitly barred from accessing, given hierarchical constraints. Editor: And the humble materials! The canvas, the raw wood of the frame—so different from the opulence often associated with Baroque art. It disrupts that easy association with power. You're forced to confront art as a material object, one requiring tangible labor, embedded in a social matrix. Curator: And perhaps even a bit self-aware or self-deprecating on Gijsbrechts's part, to lay bare his canvas as a canvas, at once revealing and ironically flaunting his technical abilities. There’s a playfulness to its presentation that invites reflection. Editor: It’s like a commentary on the very system upholding him and other artists, by stripping away the layers of aesthetic perfection, we question the economic base that fuels all of this artistic output. Thank you, it's a lot more impactful now, knowing its sociopolitical setting. Curator: A fascinating dialogue to be had from something ostensibly so straightforward, which I think goes to the work's overall significance and impact even now.

Comments

statensmuseumforkunst almost 2 years ago

⋮

When viewed from a distance we are genuinely fooled into believing that the artist has left a painting standing on the floor with its back turned outwards. As you approach the painting its deception is revealed. What appeared to be the back of a framed painting is actually the front of a canvas. The deception is evoked by means of shadows: the shadows cast by the decorative frame onto the stretcher; the shadows cast by the stretcher onto the back of the canvas, and the shadows cast by the small note and the nails. In order for the deception to fully work the painting should be placed so that its faux shadows are in keeping with the light sources available in the room in which it is placed. With its ability to surprise and cheat spectators this work was eminently well suited to a cabinet of curiosities, or "kunstkammer". This “Back of a Painting" was presumably painted for the entry room of the Royal Danish Kunstkammer, the so-called Perspective Chamber. Gijsbrechts was court artist to the Danish king during the period 1668-72.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

statensmuseumforkunst almost 2 years ago

⋮

The eye is certainly deceived. From a distance you truly be-lieve that the artist has put down a painting on the floor with its reverse facing out-wards. As you approach it, you realise the deception. We are facing one of the few works of art in the world to have two backs. With its ability to surprise and mislead spectators this work was an obvious choice for a ‘kunstkammer’ (cabinet of cu-riosities). The easel also on display in this room is de-scribed in the first inventory list of The Royal Danish Kun-stkammer as ‘a fruit piece with artist’s paraphernalia painted in perspective.’ Back then the Kunstkammer was still housed at the Copenha-gen Palace, but when the King set up a new Kunstkammer the work became part of the so-called Perspektivkammer. ‘Reverse’ was presumably part of the Easel.

statensmuseumforkunst almost 2 years ago

⋮

With the absence of the frame that traditionally serves as the architectural transition between the spectator’s reality and the picture’s painted universe, this work by the Flemish painter Gijsbrechts is moving beyond the usual realms of art and into the illusionistic domains of the stage. The deception of the eye is certainly there. When viewing the picture from afar, we are truly cheated into believing that the artist has left a painting behind on the floor with its reverse facing outwards. With its ability to surprise and deceive the spectators, this work was eminently qualified to be part of the royal Kunstkammer. Another cutout - showing an easel bearing a still life and the reverse of a painting standing at its foot, the actual panel cut out to follow the contours of the objects painted on it - is described in the Royal DanishCabinet of Curiosities’ first inventory from 1674 as: "A stand with painter’s paraphernalia painted on perspective." Back then the cabinet of curiosities was still housed at the Copenhagen Castle, but a few years later when the monarch set up the cabinet in a new building, the present-day Danish National Archives, the easel became part of the décor of the entrance hall where it was presumably joined by The Reverse of a Framed Painting.