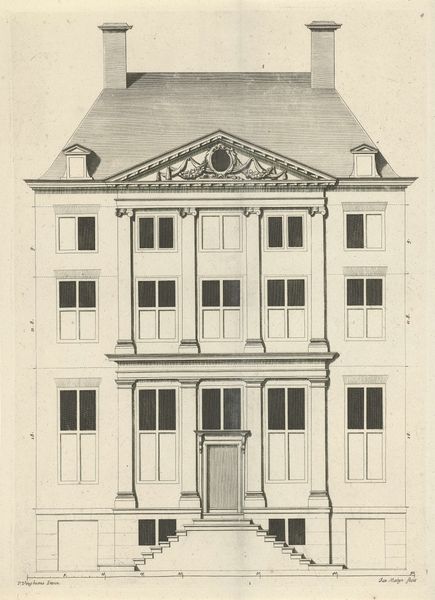

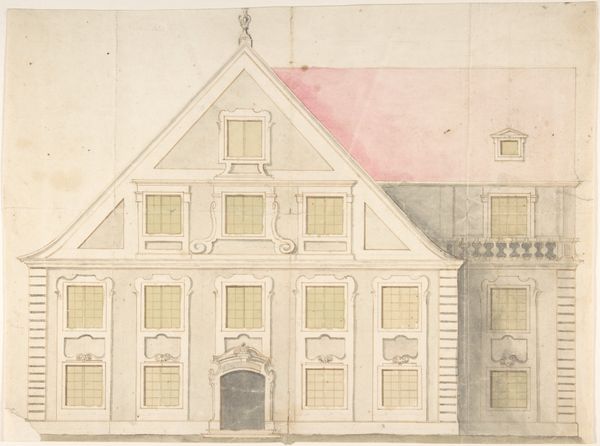

drawing, etching, paper, pen, engraving, architecture

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

#

etching

#

paper

#

architecture drawing

#

pen

#

cityscape

#

engraving

#

architecture

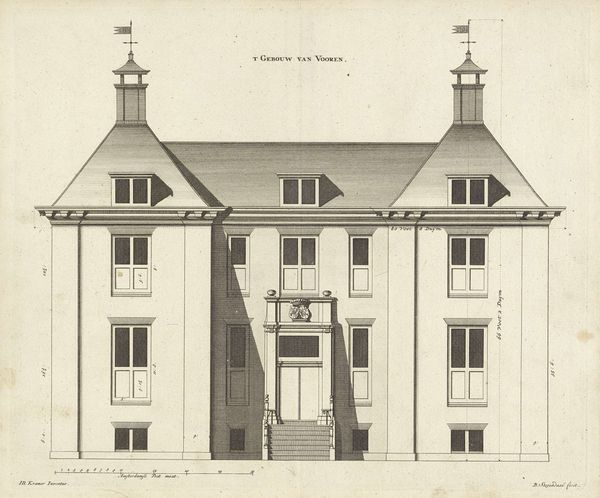

Dimensions: height 225 mm, width 333 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's turn our attention to "Huis van Constantijn Huygens van voren gezien," or "House of Constantijn Huygens seen from the front," an architectural rendering from 1639. Theodor Matham rendered it in pen, etching, and engraving. What strikes you about this portrayal of domestic life? Editor: The sheer formality! There’s a chilliness, almost a blankness, despite all those meticulously rendered details. It feels more like a blueprint than a lived-in space, a statement of wealth and status rather than a home. Curator: Absolutely. We have to consider Constantijn Huygens himself, a towering figure in Dutch Golden Age society—a diplomat, composer, poet, and scholar. Matham’s print is less about architectural innovation, and more about enshrining Huygens' prominence and good taste. Editor: So the house functions as a symbolic extension of Huygens' personal brand, in a way? Those rooftop sculptures and finials seem pointedly classical, associating him with a legacy of power and learning. Curator: Precisely. And that inherent accessibility speaks volumes, doesn't it? Matham ensures its grandeur is on full display, easily consumed and disseminated within print culture, emphasizing its owner’s sophisticated participation in a broader European intellectual sphere. Who is this imagery trying to reach and how is it serving the image and politics of the sitter? Editor: Yet, I wonder about the implications of such rigid visual control. Doesn’t it, paradoxically, render the actual inhabitants invisible? Are the enslaved persons, the people performing the labor necessary to maintain this establishment and support his household being completely erased from view in order to advance a singular ideology about Huygen and the time period? Curator: It's a sharp observation and that void really underlines the political function of these kinds of images in reinforcing social stratification. Matham, intentionally or not, creates an enduring symbol of privilege. Editor: Looking at this piece has made me question who, or what is erased through architecture in our time? How are present power dynamics perpetuated or hidden by our physical surroundings? Curator: A relevant thought to bring forward, underscoring how even seemingly straightforward depictions like this one reverberate far beyond their immediate historical context.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.