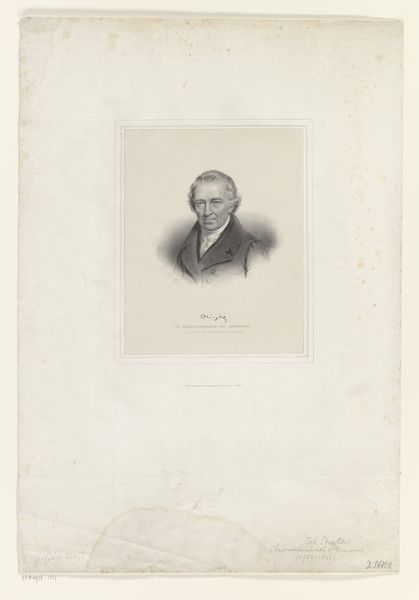

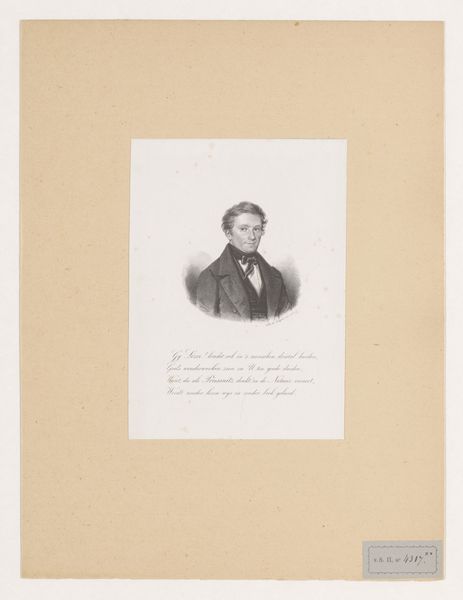

drawing, print, pencil, graphite

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

light pencil work

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

pencil

#

graphite

#

academic-art

Dimensions: height 495 mm, width 330 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is a portrait of Rembertus Westerhoff, created sometime between 1843 and 1863 by Johan Hendrik Hoffmeister. It is rendered primarily in pencil, with elements of graphite, and was subsequently reproduced as a print. What’s your first reaction to it? Editor: Austere, very much in keeping with formal portraiture of that era. The precise rendering of the gentleman’s suit and the slight shadow behind him contribute to the work’s serious and respectable atmosphere. It looks like a woodburytype; tell me about the printing process that enabled production of this portrait. Curator: Indeed. We can see the detailed texture and tonal gradations possible through graphite pencil drawing combined with the woodburytype printing process, an innovation using gelatin relief. The graphite enables meticulous detail that could then be reproduced uniformly through the mechanics of gelatin transfer, giving us some insight to accessibility of images to wider social groups. The layering involved suggests labor beyond initial artistic touch. Editor: I am particularly struck by how the print medium democratized image-making. A photograph, while becoming increasingly available, still wasn’t quite the accessible commodity that these reproductive prints were becoming in the mid-19th century. Do we know anything about the original drawing's circulation? Did it become part of a broader series? Curator: The drawing's journey through production would tell of its inherent value and perceived cultural importance beyond a unique artwork to display. This allowed for wider societal dissemination, with portraiture acting as powerful vehicle for representation of not only physical likeness, but ideological messaging too. The suit he wears, for instance, speaks volumes about contemporary ideas of wealth and prestige. Editor: Absolutely, consider too how portraits like these played a crucial role in solidifying social status, especially for emerging professional classes. It's not merely an image, but a declaration, carefully crafted through the technology available, to reinforce social standing in a shifting social climate of nineteenth-century Netherlands. Curator: So in understanding the portrait of Westerhoff here, both as artwork and as social object, we appreciate not just a likeness, but the machinery by which it became multiplied, disseminated and therefore instrumentalized in an increasingly visual world. Editor: Agreed, understanding its making, as well as reception, underscores the layered complexity of an image produced during a critical period of social change and industrial expansion. Thank you for highlighting this important context!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.