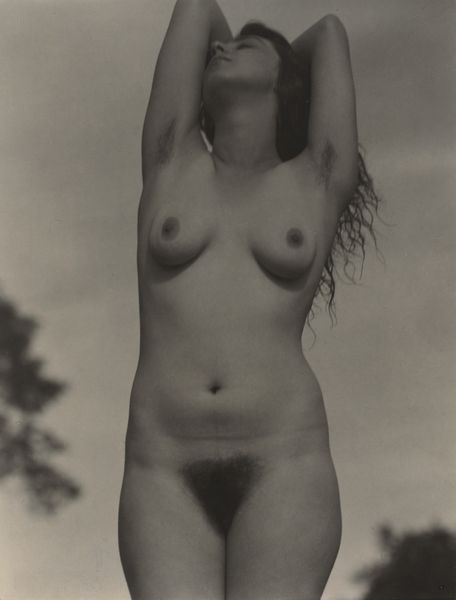

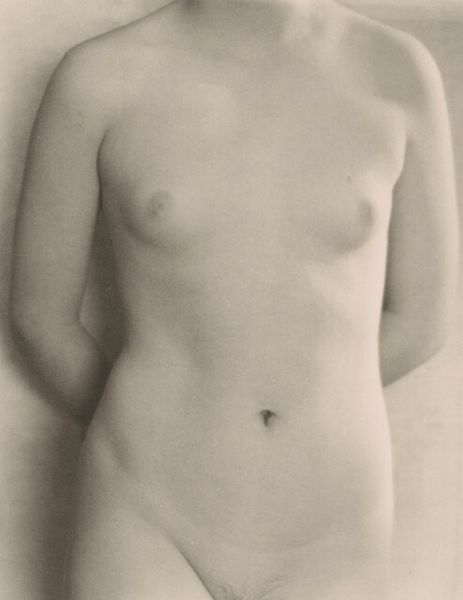

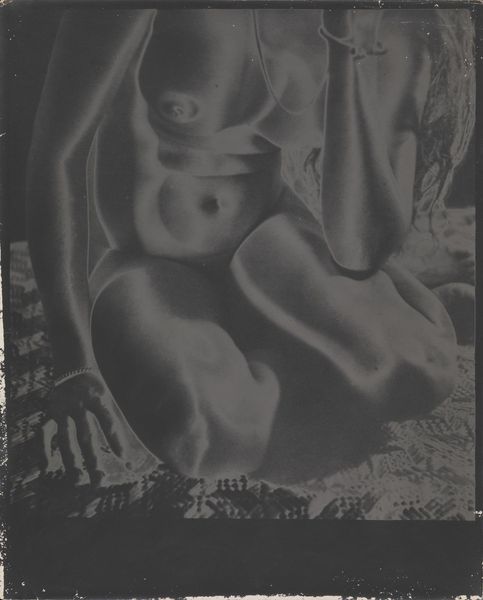

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

pictorialism

#

photography

#

black and white

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

monochrome photography

#

monochrome

#

nude

#

modernism

#

monochrome

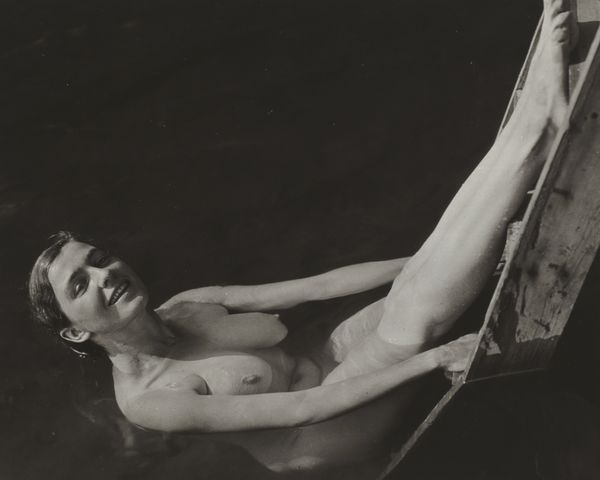

Dimensions: image: 11.7 × 8.6 cm (4 5/8 × 3 3/8 in.) sheet: 12.6 × 10 cm (4 15/16 × 3 15/16 in.) mount: 33.7 × 27.1 cm (13 1/4 × 10 11/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

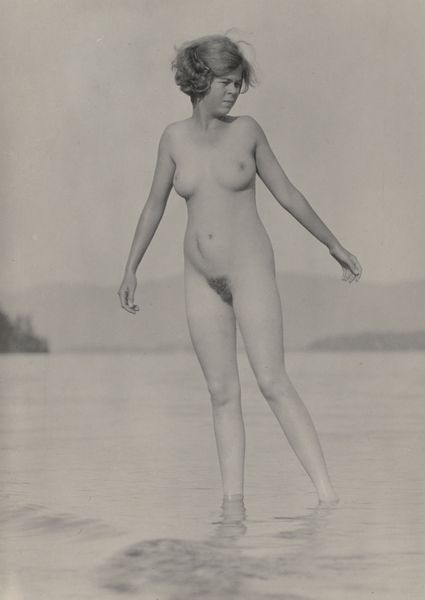

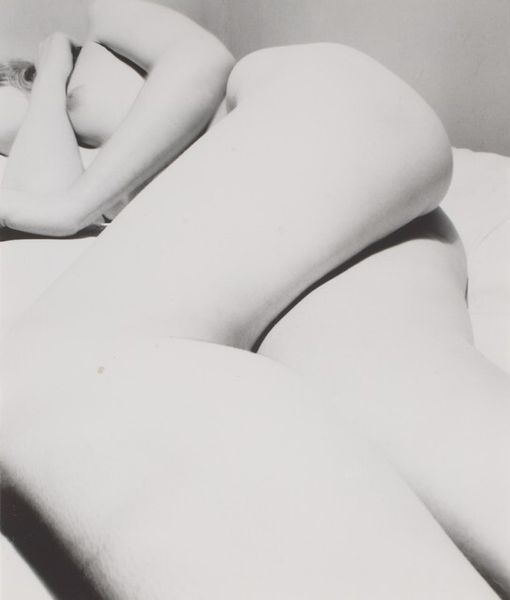

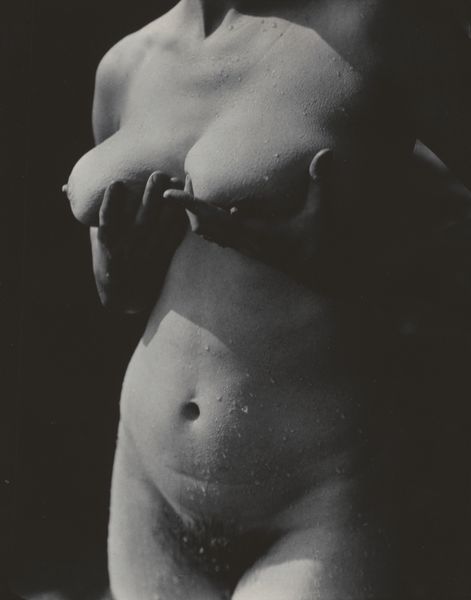

Editor: So, this is Alfred Stieglitz’s "Rebecca Salsbury Strand," taken in 1922, a gelatin-silver print. It’s strikingly intimate, the way the water seems to both reveal and conceal. What stands out to you when you look at this? Curator: What immediately strikes me is the cultural context. Stieglitz, at this time, was deeply involved in the Photo-Secession movement, pushing photography towards fine art status. Nudes, while not uncommon, were often treated differently. Considering the history of art institutions, how do you think exhibiting a piece like this challenged existing power structures and the male gaze? Editor: I see what you mean about challenging power structures. Maybe its power is that it seems so matter-of-fact, avoiding idealization? Curator: Precisely. It wasn't about classical beauty, but capturing a moment, a reality. The Pictorialist elements softened the photograph, lending a painterly effect, but it also subtly redirected the male gaze – shifting it, perhaps, towards something more… human, more connected. Stieglitz, through his gallery "291", was trying to instigate conversations about modern art's role in society, so what kind of a statement do you think including a photograph like this would make in his total aesthetic program? Editor: It makes me think about how art constantly redefines boundaries, challenging both artistic and social expectations. It sounds like Steiglitz wanted to democratize the definition of beauty and that museums can do the same by representing artwork that defies what is expected. Curator: Absolutely. Thinking about its place in shaping public perception enriches our appreciation of art like this.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.